“84 Charing Cross Road” & “221B Baker Street”: Chronicles of Connection

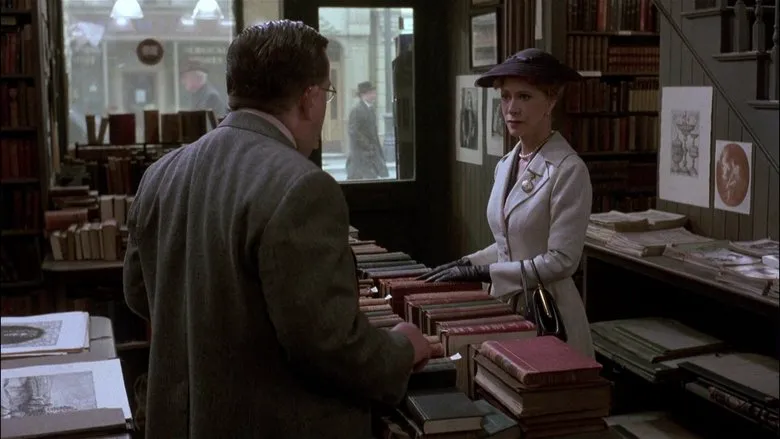

This film, “84 Charing Cross Road,” brings to life the charming correspondence that blossomed into a profound, enduring bond between a New York City writer and a London bookshop. It’s a testament to the power of shared passions and human connection, transcending oceans and time.

The Genesis of an Unlikely Friendship

The story unfolds with a simple yet extraordinary beginning: the date on Helene Hanff’s first letter, October 5, 1949. Helene, a spirited and discerning writer dwelling in the bustling heart of New York City, stumbled upon a compelling advertisement for Marks & Co. in a magazine. The ad proudly proclaimed their specialization in “out-of-print books,” a beacon of hope for Helene who struggled to find the literary treasures she craved in her local market. Price was a significant barrier; the books she yearned for were prohibitively expensive, while the affordable options were mostly American bestsellers that didn’t pique her interest.

With nothing to lose, she meticulously listed three titles and boldly stated her financial limit: “none cost more than five dollars.” To her delight, two books promptly arrived, accompanied by a modest invoice. This initial exchange laid the foundation for a relationship built on something rare and beautiful: unreserved trust between strangers.

The bookshop, across the vast Atlantic, demonstrated remarkable good faith, seemingly without a second thought that Helene might default on payment. Helene, in turn, reciprocated with immediate and genuine kindness. Eschewing any attempt at bargaining, she enclosed the payment with her very first letter. But more than just payment, she launched into a “chatty mode,” a disarming candor that spoke volumes, as if she were addressing old friends. She wrote with a bubbling enthusiasm:

This uninhibited expression, sharing profound feelings about a simple book with complete strangers, is utterly admirable. Many find it challenging to voice even casual feedback, be it to bookstore staff or a waiter. Helene’s openness, her willingness to treat these unknown recipients of her letters as friends with whom she could share her deepest joys, truly set the stage.

Helene’s letters were characterized not just by their warmth, but also by a playful pragmatism. Unsure how to convert British pounds to US dollars, she sought help from her upstairs neighbor’s British boyfriend, Brian, relying on them and the bookshop for her impression of Britain. She then politely requested that future invoices be converted into US dollars. Her requests were always impeccably worded, devoid of any demanding tone. This was because her aim wasn’t a calculated maneuver for a specific goal, but rather a sincere overflow of her personality that naturally led to practical outcomes. It’s a subtle art of communication that many of us still strive to master.

Even the initial formalities soon gave way to genuine affection. Though the bookshop initially addressed her as “Madam,” Helene subtly conveyed her dislike for the title, hoping it didn’t carry the same stiff formality in England as it did in America. The bookshop, too, had its practical requests, advising Helene against sending cash directly due to security concerns, preferring safer postal money orders. These small exchanges, full of politeness and evolving comfort, paved the way for deeper connection.

Inside Marks & Co.: The Heart of the Letters

The People Behind the Pages

The establishment itself was owned by Mr. Marks and Mr. Cohen, but the daily operations and the heart of the correspondence were handled by a dedicated few. The core staff included Frank Doel, the meticulous manager; Megan Wells, the owner’s secretary; Bill Humphries, the diligent cataloger; Cecily Farr; and George Martin. Gradually, Helene’s circle of correspondents expanded to include Frank’s wife, Nora, and their eldest daughter, Sheila – who charmingly referred to herself as the “Third Correspondent of the Doel Family.” Even their neighbor, the kindly elder Mary Bolton, joined in the letter-writing, adding her unique perspective.

The passing years brought inevitable changes. Mary, in her eighties, eventually moved to a nursing home; George Martin passed away prematurely; Cecily embarked on travels to the Middle East with her husband; and Megan, after planning to settle in South Africa, ultimately returned home. Bill, living with his 75-year-old great-aunt, became one of the last remaining familiar faces alongside Mr. Cohen after Frank Doel’s passing in December 1968, followed by Mr. Marks. The volume of correspondence naturally diminished as the original cast dispersed.

The Reciprocity of Kindness

The gifts exchanged between Helene and the bookshop were not just material items; they were tokens of deep thoughtfulness and growing affection. The bookshop staff consistently sent Helene carefully chosen selections, like a small, exquisite copy of A Collection of Elizabethan Love Poems—a book Helene had specifically mentioned wanting for her birthday. They thoughtfully included a message on a card, signed by everyone, rather than defacing the book itself. Helene cherished this gift, highlighting its profound importance to her. ” Frank even shared practical advice, teaching her the proper way to care for delicate second-hand books. The books themselves were always packaged with utmost care, such as the described “white softcover Catullus, complete with a white silk bookmark.”

The warmth extended beyond Helene herself. When her friends visited Marks & Co., the bookshop staff treated them like beloved family members. Helene’s friends reported back, delighted and slightly overwhelmed: “We only had to say we were your friends to be surrounded… They all insisted on treating us like royalty, and we nearly died of kindness!”

This evolving relationship was beautifully mirrored in their correspondence.

Initially, Frank Doel appeared formal and even stern to Helene, an impression he later clarified. He explained that his early letters “had to be kept as business records, so I thought it would be more appropriate to be formal” – a charming detail that subtly countered any overly romantic interpretations of their initial business exchanges. The staff eagerly anticipated Helene’s letters, often sharing her delightful observations aloud. Cecily, for instance, envisioned Helene as “a young, educated, and fashionably dressed woman,” while the curmudgeonly old Mr. Martin, despite Helene’s sharp wit, stubbornly insisted on viewing her as a serious academic.

This curiosity about one another was reciprocal and purely born of friendship, devoid of any gendered assumptions or predefined roles. Cecily, sensing Helene’s inquisitiveness, even shared a “secret”: “If you are curious about Frank, I can tell you secretly: he is nearly forty, very handsome, and married a beautiful Irish girl – I think it’s his second wife.” It was clear they viewed each other as genuine human beings, not mere archetypes. Helene, ever honest, humbly declared, “I have no education at all, not even a college degree! I just happen to like reading.” (A sentiment many book lovers can strongly identify with!).

The bedrock of their friendship was their willingness to share the mundane and the profound, the joys and the complaints. Helene shared details of her work life, her hobbies, the frustrations of being evicted, and even a humorous complaint about a particular book she disliked. In return, the bookshop staff opened up about their family matters and personal misfortunes: Nora’s hospitalization, Cecily’s travels, and the somber news of Martin’s death. Their correspondence was a breath of fresh air, a complete departure from the societal pressure to “only report good news,” embodying the true essence of supportive friendship.

Post-War Realities: Britain vs. America

The letters served as a remarkable window into the socio-economic realities of immediate post-war Britain and how they starkly contrasted with life in America.

Austerity in Britain

After the devastating end of World War II, Britain endured several years of stringent rationing. Helene was “horrified” to learn about the meager allocations: each household received only two ounces of meat per week, and each person was allotted just one egg per month. Nora and Frank elaborated on the grim details, mentioning that “occasionally, due to shortages, the rations were temporarily reduced,” forcing them to “trade other things for canned goods.” By 1952, “there were no ration reductions,” but Nora still regarded the canned dried eggs Helene sent as a true godsend.

Frank, in a poignant admission, wrote, “The items you sent, we either haven’t seen in a long time or only catch a glimpse of them on the black market.” He added solemnly, “We haven’t seen a whole piece of meat in too long.” This desperate situation inadvertently fueled a burgeoning black market, as opportunistic businessmen emerged, like a British company in America specializing in purchasing and shipping supplies from Denmark to hard-hit Britons.

Such conditions were almost unfathomable to most Americans, much as we in the present day find the plight of ordinary people caught in distant conflicts to be from another world. For several years, Helene regularly sent parcels of hams, eggs, raisins, tinned meat, and invaluable stockings for Western holidays like Easter and Christmas. Her thoughtfulness was truly exceptional. The story of the stockings stands out: Nora had mentioned having to trade a pair for a can of dried eggs, a testament to their scarcity. Helene immediately contacted a friend traveling to London, asking her to bring four pairs – only for the friend, a performer, to arrive with an impressive two dozen. This small act of kindness provided both practical relief and crucial emotional comfort.

This echoes a universal truth. Growing up in the rural 1990s, where resources were often scarce and basic needs sometimes questioned, one remembers relatives sending money and goods from the city despite their own struggles. The underlying principle remains throughout time and across cultures: human nature, in its capacity for empathy and generosity, is profoundly consistent.

Beyond food, the letters chronicled other aspects of post-war recovery. In 1952, Nora noted that most new cars in Britain were exported, with only a small quota reserved for domestic buyers, leading to five to six-year waiting lists despite high costs. Frank’s family rejoiced when they managed to acquire a used car, “finally join[ing] the ranks of car owners,” highlighting persistent transportation difficulties which had curtailed family travel after the war. By September 1953, Cecily could deliver hopeful news: “Everything is no longer rationed, and stockings can be bought in slightly better stores.”

However, freedom from rationing did not instantaneously mean abundance. In 1968, Frank’s youngest daughter, Mary, got engaged, but marriage was postponed because “both sides were not financially well-off.” The war’s legacy extended directly to Frank’s personal life too; his first wife had been a casualty of the conflict, leaving Sheila motherless at a young age. Politically, the bookshop staff harbored widespread hopes that Winston Churchill would win the election, believing he possessed the foresight to guide them to a better life – a common sentiment in an age yearning for stability.

Through these granular details, one can witness the gradual resurgence of the British economy. Helene, for her part, playfully encouraged Sheila and Mary to “settle down and produce for the country,” underscoring an era still reliant on a large workforce for economic development. The rise of tourism became a verifiable indicator of recuperation: in May 1957, Frank observed “more American tourists this year than ever before,” many of them Beatles fans, a sign of Britain’s growing cultural magnetism. This trend escalated; by October 1965, “There are more tourists this year than in previous years,” and by October 1968, a dramatic shift: “Large numbers of tourists from America, France, Northern Europe, and other countries have almost cleaned out all our better leather-bound books… Book sources are scarce… Book prices are rising…” Tourism clearly proved to be a powerful engine for economic growth.

These personal narratives subtly unveil the shifting global power dynamics. Cecily’s husband, a soldier, being deployed to the Middle East, with her following, hints at Britain’s continued involvement in post-colonial conflicts, often in alignment with American foreign policy. Another significant detail highlights Britain’s social progress: Nora’s hospitalization for several months, where she “hardly spent a penny” thanks to the nascent National Health Service, a testament to a foundational national policy.

Challenges in America

While British life was defined by austerity, America wasn’t without its own challenges, albeit of a different nature. Helene faced the unsettling reality of eviction when her apartment building was slated for a new development. Her landlord, intent on forcing tenants out, employed aggressive tactics:

My landlord, afraid that everyone would stay, simply fired the doorman, so no one takes care of the trash or hot water; he also plans to tear down the mailbox room, the hallway lights, and the partition wall between my kitchen and bedroom (happening this week)…

Sympathy for Helene’s plight is immediate, yet this passage also prompts reflection on the often-romanticized notion of “free America.”

Helene herself injected a dose of sharp sarcasm into her observations about American foreign policy, wryly remarking on “A ‘steadfast ally’ that spends lavishly to help Japan and Germany ‘recover’ from defeat, but watches its British compatriots suffer from hunger.” This pointed critique offered a grounded, unfiltered perspective on international priorities from a citizen navigating her own daily struggles.

The Art of Translation: Beyond Words

Having read the Chinese translation, the original reviewer felt compelled to seek out the original English version, a significant compliment to the translation’s ability to ignite further interest. From an “accuracy and elegance” standpoint, the Chinese translation earned full marks, especially Helene’s spirited, playful, and utterly charming tone, which was superbly rendered. It’s noteworthy that this appears to be the sole Chinese translation available, underscoring its classic status and quality.

However, the reviewer identified a notable challenge in terms of “faithfulness” – specifically, the translator’s choice not only to convert the language but also to infuse British and American cultural nuances with overtly Chinese cultural elements.

The most illustrative example of this approach lies in a truly “classic” passage:

The boss didn’t say “rabbit pocket feet,” he said “potato glue”!—I also think this is the only reasonable name. Think about it: beans grow in the soil, so calling it “potato” makes sense; digging it out of the soil, “stirring” and “stirring” it into a “glue” state, doesn’t it become “potato glue”! Isn’t this word closer to the truth than “peanut butter”? You really don’t understand Mandarin!

Translating an original English pun into a culturally resonant Chinese pun is an astounding display of linguistic prowess and creative ingenuity. It transcends mere word-for-word translation, transforming it into a new, clever play on words. Yet, as the reviewer aptly questions, does it retain any trace of the original English culture? Does it imply Americans suddenly speak certain Chinese dialects? This highlights the eternal dilemma in translation: how to balance linguistic brilliance with unwavering cultural fidelity.

This narrative beautifully illustrates a timeless truth: those who genuinely love books are often imbued with an inherent kindness towards the world, a connection that transcends geographical and cultural boundaries. This film serves as a gentle reminder to cherish unexpected bonds and the simple, profound joy of shared humanity.