Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris is not merely a science fiction film; it’s an introspective journey into the depths of the human psyche, a haunting exploration of memory, guilt, and the limits of understanding. Right from the film’s opening, Tarkovsky employs a prolonged, mesmerizing shot that disrupts our typical sensory engagement. The camera lingers on the minutiae of nature—flowing water, swaying foliage—before gradually pulling back to reveal the protagonist, Kris Kelvin, his gaze distant and hollow. This initial sequence establishes Kelvin’s detachment, his unwillingness or inability to act as an interpreter of the world. He is no longer responsible of observation or as the intermedium of world.

The Limits of Transcendence

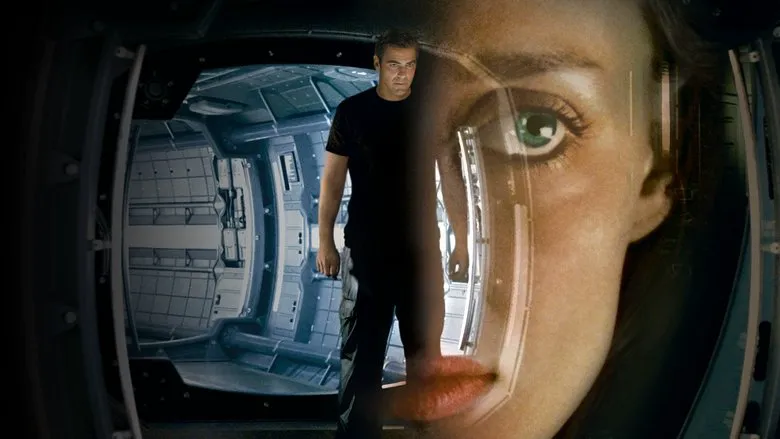

Comparisons are often drawn between Solaris and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. While both films venture into the realm of the cosmos, their approaches diverge significantly. 2001 presents a transcendent, almost god-like perspective. We, as viewers, are positioned above the narrative, privy to information and insights inaccessible to the characters within the film. This grants us a sense of intellectual gratification, the pleasure of deciphering a grand cosmic puzzle. Solaris, however, thwarts this desire. It resists easy interpretation, leaving many viewers frustrated by its ambiguity. Some critics even dismiss it as a personal and obscure exploration of love and humanity masquerading as science fiction, accusing Tarkovsky of prioritizing interpersonal relationships over grand, sweeping themes.

Private Gaze and Unknowable Depths

Kubrick offers an epic vision, focusing on the broad sweep of history and humanity’s place within it. Tarkovsky, in contrast, offers a perspective in Solaris that feels intensely subjective, almost voyeuristic. The extended observation of Kelvin sleeping, for instance, isn’t intended to convey a specific idea. Rather, it evokes a liminal space, a symbolic void representing the failure of interpretation. This space is similar to the feeling we get in horror movies when there is an unknown presence behind a door, but the feelings stems from the lack of anything behind the door afterall. It creates the potential for form that contains nothing, it acts as a threshold that is normally hidden in film language. This void becomes a catalyst for intense emotional turmoil, not born from tangible events, but from the very absence of them. The film deliberately avoids easy explanations, embracing the unknowable.

The Return of the Absent

This absence takes a disturbing turn with the reappearance of Kelvin’s deceased wife, Hari, resurrected by the enigmatic forces of the Solaris ocean. This resurrection creates a Hegelian paradox where the of absence is switched with the return of a something that wasn’t there before… The film is filled with uncertainty and doubt. Like the old pilot Burton from the beginning of the movie, the human mind is afloat and the ocean defies collective rational thought. Tarkovsky delves into the construction and deconstruction of the “human” itself, while Kubrick is trying to illustrate the begininngs of humans.

The Dissolution of Boundaries

In Solaris, the narrative unfolds entirely within the confines of human consciousness, blurring the lines between subject and object, reality and illusion. The self becomes fragmented, its boundaries dissolving. When Kelvin confronts the resurrected Hari, he attempts to destroy her, not because she is an external threat, but because she originates from within himself, from the depths of his own psyche. She is no longer an unknowable entity, but a projection borne of his unconscious desires and regrets. This full understanding causes failure. Staring a too long at Solaris opens an eternity of gap, a gaze that causes the things in side you to stare back at him.

The Perilous Gaze

Tarkovsky masterfully utilizes cinematic techniques to evoke a sense of unease that is often found in horror films. This constant sense of being watched is a result of everything. In the old barn the crack in the barn that the main character is sacred of presents the fear, just as it does in the strange tapes that Burton plays in his pre-flight briefing. The human mind is going to try to reconcile what is see, but if it is to fall short, then that is when paranoia begins. Solaris is the antithesis of an ability to rationalize. It expresses meaninglessness in any human that has the intention of attempting to find the meaning of the world that they live in. It becomes pure and absolute essence.

Confronting the Void

What, then, resides within Solaris? The answer, perhaps, is nothingness is the truest answer. What is tangible here changes too fast to be concrete and the camera can’t capture them. Solaris forces humans to confront the trauma of yesterday, as exhibited by the scalding water running down the face of the father at the end of the movie. Just as as Kelvin first confronts his wife who has manifested it shows humans destroying something so that they can return to a previous reality.

“Am I killing me?”

When one gazes into the abyss, what truly stares back? When the crew of the space station feel threatened by ghosts of their past, what has manifested? The human body has manifested itself. One is in essence, staring at itself, or in other terms, its own abyss. The void that Solaris causes enlarges a persons abyss that lives inside, until the point it escapes and threatens its host. Kelvin is staring into nothingness and his staring merely opens his abyss to swallow him. Someone else is not just staring and attempting to harm me in that intangible place, but it is me who is attempting nefarious action. Only then do we get to asking the question, “Am I killing me?”