A Deep Dive into Spike Lee’s “Do the Right Thing”

By James Brown

He brought the music wherever he went. From the film’s opening, he advises a kid sitting on a stoop to “do the right thing,” amidst the dizzying summer heat and the blare of Radio Raheem’s boombox. Raheem, always silent yet ever-present, played by Bill Nunn with a mix of anger and benevolence, filled the frame whenever he appeared. His music was his voice, constantly blasting Public Enemy’s “Fight The Power.”

Do the Right Thing (1989)

He moved within the echoes of music, a formidable and indispensable presence, radiating aggression and vitality. Radio Raheem spoke sparingly, yet his voice, amplified by his ever-present boombox, commanded attention. Through sound alone, he distinguished himself, asserting his individuality.

The Complexity of Human Experience

Human experience, both collectively and individually, is a stubborn voice, refusing to be confined to a single expression. To say that Spike Lee’s searing masterpiece, Do the Right Thing (1989), is simply a commentary on race relations would be a gross oversimplification. It’s a diverse and volatile work, a dangerous yet poignant attempt to capture the multifaceted nature of humanity.

This complexity is evident from the very beginning. Editor Barry Alexander Brown’s opening montage is a vibrant tapestry, immediately immersing us in the film’s intricate world. The colors are a character in themselves. The sweltering Brooklyn heat, money, ownership, and melting ice all contribute to the oppressive atmosphere, mirroring the cacophonous music that surrounds the characters.

In the meticulously crafted microcosm of Do the Right Thing, everything feels heightened, more intense than it should be. The human condition is laid bare, making the summer feel like a year of anxieties.

Character Studies in a Boiling Pot

Another striking scene introduces Tina (Rosie Perez), a young mother on the verge of collapse. She navigates her dilapidated apartment near the train tracks, tending to her child while shouting at her mother in Spanish. Tina’s constant movement, sometimes shrouded in shadow, sometimes bathed in prismatic orange light, combined with the camera’s rapid retreat as she approaches, creates a sense of her being about to burst from the frame.

Later, in an intimate and objective shot, Mookie, played by Spike Lee himself, thanks God as he runs an ice cube over Tina’s body, as if preparing her for surgery. In this scene, Lee seems to be telling Perez, in her first film role: This is a new character I’m entrusting to you.

While Lee’s narratives often veer towards tragedy – blood, the Billy Club, the summer heat, and the street’s water hydrant – his artistry lies in his deceptive portrayal of everyday life within this community.

The camera introduces us to each family, each child, and Lee makes sure to acknowledge them, even scolding them for their greetings. There’s Da Mayor (Ossie Davis), the drunken block elder; Mother Sister (Ruby Dee). The names themselves hint at their roles. The three elders sit on the curb, backs against a fire-engine red wall, gossiping and complaining.

In this, his third film, Lee’s genius shines: his love for the community and his visually striking, character-driven style. The characters are constantly talking, yet surprisingly vulnerable. Lee’s orchestration is filled with impromptu wit, like poetry found on the streets.

The film’s visual style is humane, the colors dizzying, and the curiosity about others palpable. In Malcolm X (1992), Lee cast Denzel Washington in the lead role. In Bamboozled (2000), Savion Glover and Tommy Davidson played musical minstrels. And When the Levees Broke: A Requiem in Four Acts (2006) focused on the victims of the U.S. government’s inadequate response to Hurricane Katrina, a focus born of both visual and moral concern.

Bamboozled (2000)

Ernest Dickerson’s cinematography intensifies this ethical sense, emphasizing the camera’s symmetry and synchronized movements. Costume designer Ruth E. Carter dresses the actors in vibrant, contrasting colors. Production designer Wynn Thomas transforms Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, into a stage for conflict and contradiction.

These elements allow Lee to realize his vision: the 360-degree tracking shots around characters, not seen in Do the Right Thing but fully realized in the following year’s Mo’ Better Blues (1990). Do the Right Thing can be seen as a precursor to Mo’ Better Blues, painting a poignant portrait of Radio Raheem.

Mo’ Better Blues (1990)

Icons and Idols

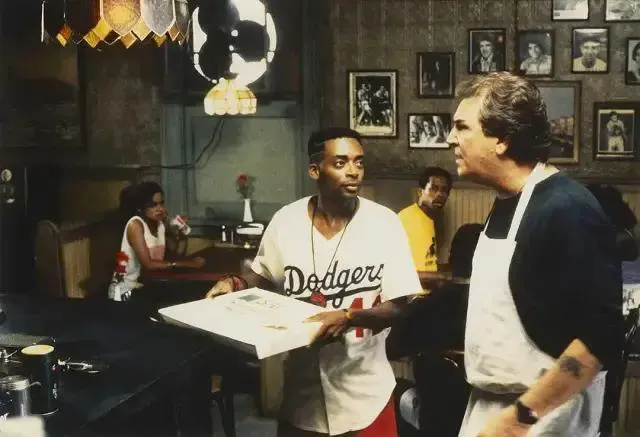

Iconography is everywhere in Do the Right Thing. Behind the cash register at Sal’s Famous Pizzeria hangs a painting of Pope John Paul II. The trouble begins at Sal’s “Wall of Fame,” featuring Italian-American celebrities like Frank Sinatra, Al Pacino, and John Travolta, meant to inspire Sal (Danny Aiello) and his sons, Vito (Richard Edson) and Pino (John Turturro).

Giancarlo Esposito’s character desires more Black faces on the wall to better serve Sal’s Black clientele. The local radio DJ’s (Samuel L. Jackson) studio walls are adorned with posters of Keith Sweat, Whitney Houston, Tracy Chapman, and Anita Baker. Smiley (Roger Guenveur Smith), who stutters, sells graffiti portraits of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. In Lee’s films, the interest in faces is unwavering, almost religious.

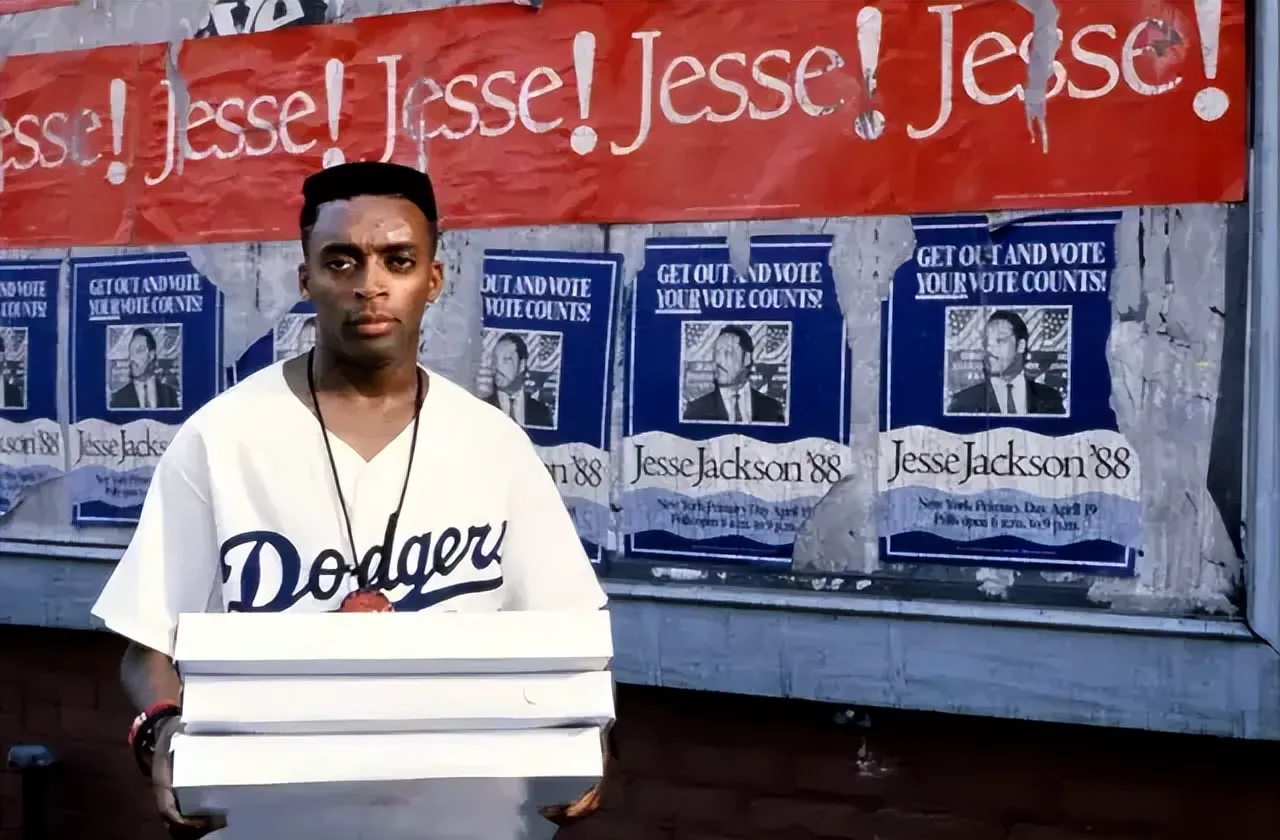

Let’s revisit Spike Lee’s portrayal of Mookie, the most dangerous and accomplished of them all. Lee’s willingness to embody himself in this lost, charming, and seemingly harmless character is perhaps why Do the Right Thing has remained fresh for over 30 years since its theatrical release, and why it has predicted the present era with such incredible precision.

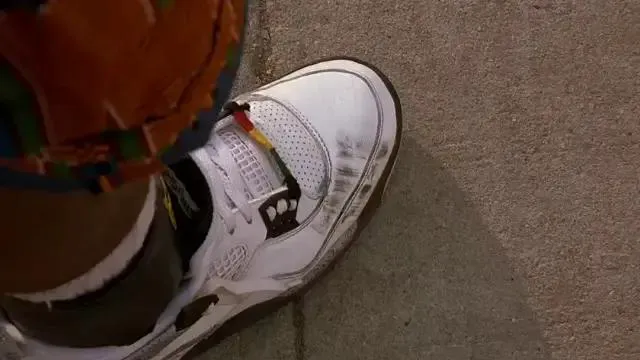

Mookie’s vintage Dodgers jersey, athletic shorts, and rare Nikes are now considered fashionable by Black youth. Even if Mookie were placed in today’s Bedford-Stuyvesant, Bushwick, Harlem, or Lower East Side, his style would still be relevant. Furthermore, Mookie uses a towel with the classic Knicks logo, which has recently regained popularity. Therefore, it is not difficult to explain that the pain in his heart carries an ironic sense of alienation.

A Reflection of Reality

When Do the Right Thing was released, its shock and immediate impact became even more justified. Lee had already established himself as one of America’s most important young directors with the success of She’s Gotta Have It (1986) and School Daze (1988). His eye for comedy was clear, as was his compassion for Black people and his deep concern for contemporary politics.

Now, he found himself immersed in New York City’s cyclical racial anxieties, fueled by state-sanctioned racist violence that permeated the city’s streets. Lee dedicated Do the Right Thing to the families of Eleanor Bumpurs, Michael Griffith, Arthur Miller, Edmund Perry, Yvonne Smallwood, and Michael Stewart, all victims of police brutality or white mob violence.

These are just a few of the Black people who died unjustly. (Incidentally, in Do the Right Thing, the crown that Smiley paints on Martin Luther King Jr.'s head looks somewhat like the crowns that graffiti artist Jean-Michel Basquiat painted to commemorate deceased Black heroes. Basquiat was horrified by Stewart’s death and created a painting specifically for the event called Defacement: The Death of Michael Stewart.)

In Do the Right Thing’s finale, after Radio Raheem is choked to death by police batons, people begin to summon the dead with sound, a practice that starts tentatively and evolves into a near-anthemic chant. The names they chant also represent those dead young Black people; the crowd in Lee’s film has clearly memorized these names—Radio Raheem is just the most recent unfortunate victim—just as contemporary audiences have their own lists of the deceased, such as Trayvon Martin, Laquan McDonald, Sandra Bland, and Philando Castile.

In 1991, two years after Do the Right Thing was released, the Crown Heights riot broke out in Brooklyn, and tensions between Blacks and Jews began to rise, echoing the conflict between Blacks and Italians (and, to a lesser extent, Blacks and Koreans) depicted in Do the Right Thing. Earlier that year, on the West Coast in Los Angeles, Rodney King was beaten by a group of highway patrol officers.

Ten years after the film’s release, in 1999, New York police fired 41 shots at Amadou Diallo, an innocent Guinean immigrant, killing him just steps from his home after midnight.

In 2014, 25 years after Do the Right Thing was released, Eric Garner’s death recalled the horrific scene of Radio Raheem’s death in the film: Eric Garner was also burly, a regular in his community, and was also inexplicably pinned to the sidewalk and suffocated to death.

Back in 1989, some viewers worried that Lee’s film might incite violence among Black audiences. What a strange and inadvertent concern, while violence continues to occur in reality. The key climax of Spike Lee’s film—death, anger, riots—undoubtedly adds a layer of empty realism to the film.

Despite the righteous anger, Do the Right Thing is an early expression of an unsettling ambivalence that would become a hallmark of Black political attitudes in the 1990s. The totemic victories and open liberal Protestantism on which the civil rights generation relied were long gone, and their fierce successors—Black art and Black power, the dual nationalism of art—were gradually waning. Now, Lee’s generation of filmmakers would begin to select the works of their predecessors and begin to move toward tentative integration. In the most chaotic moments of Do the Right Thing, I naturally think of a passage from Gwendolyn Brooks’s 1960s poem Riot:

Sweat is lumping the poor’s shirt

not lovely

like the two elate volunteers at

the Illinois

They were saluting his coming

down out of the sky

over fresh sea.

Dark and loud

unswerving

they must do

And Do the Right Thing also contains a sincere and undisguised yearning for unity and harmony. Earlier, while sitting in front of the red wall, one of the old men, ML (Paul Benjamin), was dissatisfied with the Korean grocery store across from Stuvesant Avenue and Sal’s Pizzeria—but his friends happily reminded him that he was also a West Indian, also a descendant of immigrants who came to New York across the ocean. His way of integrating into urban and rural life is different from that of the Korean couple who run the grocery store, inevitably influenced by his skin color, but his story is equally true and equally funny. Just as grocers Steve Park and Ginny Yang claim a stake in American commerce, ML also carries American greed.

Bill Lee, Spike Lee’s father, composed the score for the film, showing his love for blues music and American ballads, coupled with the rhythm of Public Enemy, even the score is mixed together. Apart from the noisy, multilingual dialogue, we can still appreciate Do the Right Thing. Each character in the film is vividly portrayed in the picture, shouting directly at the camera about the injustice encountered by the ethnic group, and the different accents between them are ironic. In the film, even prejudice is diverse.

Lee uses John Turturro’s olive skin and thick hair to make racial ambiguity a silent speech. John Turturro’s Pino hates “niggers,” but he likes Magic Johnson. None of his roars can weaken his younger brother Vito’s budding friendship with Mookie, or Sal’s infatuation with Mookie’s sister Jade (played by Spike Lee’s real-life sister, Joie Lee).

After all the violence has passed, the last scene of the film is a dialogue between Mookie and Sal, which begins with sharp words, but in the end, the two seem to have reached a reconciliation. Mookie’s friends tell him, “Don’t forget you’re Black.” But Tina just begs him to be a man. And whether Black or man, they have no real choice.

If we expect Lee to be anything other than a liberal at heart (or, pessimistically, a cautious “synthesizer,” caught between the stereo’s two speakers), we will always be disappointed. He respects and loves the radicals, admires their exaggeration and their infinite, obvious love for race and its people, but ultimately cannot see their premise. At the end of the film’s credits are two passages, one from Malcolm X, defending political violence for self-defense; the other from Martin Luther King Jr., whose passage condemns violence. Since the nineties, this undigested dialectic has been more or less the reality of our racial politics.

For Do the Right Thing, the most appropriate cultural hero may be Nelson Mandela, who is not mentioned in the film, but in my opinion, he exists in the film in an invisible way. In some ways, Spike Lee’s story is more similar to the state of white minority rule in South Africa—Sal and his sons are the minority whites living in this community, except for the cyclist—than to the broad narrative of American majority terror politics.

Less than a year after Do the Right Thing was released, Mandela was released from prison. In 1994, he was elected President of South Africa. Soon, this former radical who had zealously defended the oppressed and engaged in revolution was hailed as a symbol of global peace and liberation.

And Radio Raheem in Do the Right Thing is just a loner who loves music, and he was born to adapt to differences. When we first heard his long speech in the film after a long silence, he showed Mookie, who admired him, the rings on his hands. They looked shiny, well-maintained, and vaguely dangerous. One hand spelled out “Love” and the other spelled out “Hate.” He told Mookie the life story of “Love” and “Hate,” who fought each other stubbornly. In the end, “Love” defeated “Hate” and stayed.