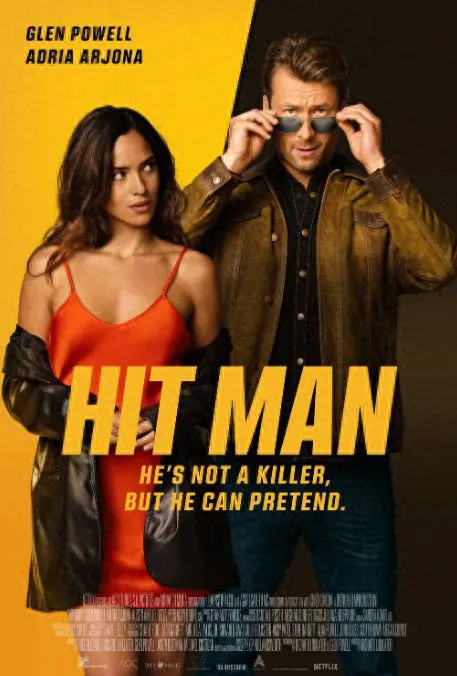

Richard Linklater’s “Hit Man” Takes the Top Spot on Netflix

Richard Linklater’s latest film, “Hit Man,” has swiftly ascended to the number one spot on Netflix, garnering widespread acclaim from both critics and audiences.

While beloved by many for the “Before” trilogy, Linklater is a filmmaker with a more complex creative identity than just the romantic long-haired protagonist wandering the streets of Vienna.

From the loose, organic, low-budget debut “Slacker” to the quintessential Hollywood inspirational comedy “School of Rock,” Linklater consistently reminds us of his versatility. It’s easy to remember him for the “Before” trilogy, but often forget that he’s also the mind behind other diverse works.

“Hit Man,” adapted from the true story of a legendary Houston undercover cop, boasts a seemingly forgettable title, yet delivers a compelling narrative.

The film is a blend of genres, described as a “hitman story, romantic comedy, and modern film noir” all rolled into one.

It possesses a visual quality that, while not immediately striking, feels like a big-budget production.

The Plot Thickens

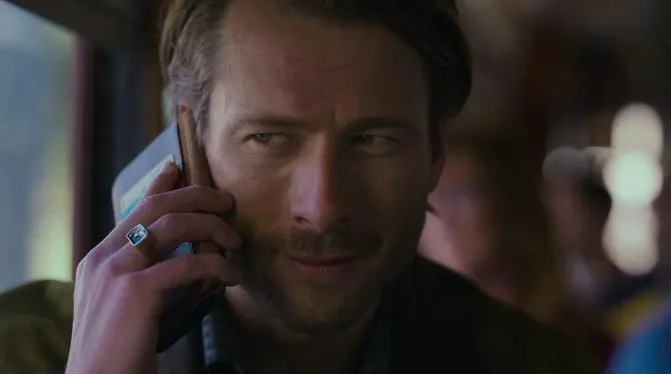

Linklater teams up with Glen Powell, who gained prominence after “Top Gun: Maverick,” and with whom he has collaborated for years. Powell not only stars in the film but also serves as a writer and producer.

The story revolves around a philosophy professor who moonlights as a fake hitman for the police, luring potential criminals. However, he falls in love with one of his clients while posing as a killer.

Beneath the surface, the film continues Linklater’s long-standing creative approach: a seemingly gentle exterior concealing a rebellious spirit and a keen, insightful understanding of human nature.

Exploring Identity and Illusion

The film opens with Gary Johnson, the philosophy professor, lecturing on Nietzsche’s philosophy of embracing risk and living in the moment.

However, a student in the back row sarcastically remarks that he’s just a “nobody driving a Honda Civic.”

The gap between one’s ideal self and reality is a central theme.

In the very next scene, the same philosophy professor, driving his Honda Civic, is tasked with an undercover police operation, posing as a contract killer to meet with potential clients.

The Fake Assassin

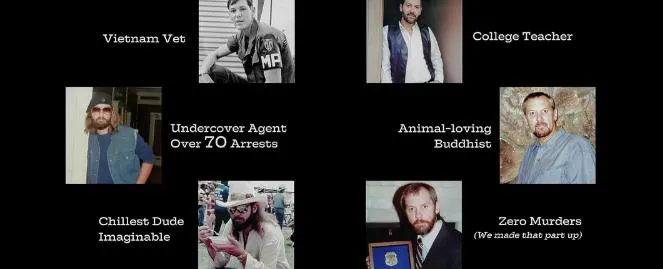

Strictly speaking, Gary isn’t a hitman, but rather assists the police by impersonating one to expose those plotting murder, preventing future crimes.

Gary believes that hitmen don’t truly exist; they are figments of imagination, fictional characters from novels and movies.

For Gary, teaching philosophy and psychology at university is theory, while pretending to be a hitman is practice.

He explores the human psyche, crafting a persona that aligns with the client’s fantasy.

However, the line between fiction and reality blurs. This “impersonation” gives rise to Gary’s alter ego, Ron, the killer.

Gary discovers that Ron is more charismatic, and people seem to like him more.

Initially, Gary creates the killer persona, but eventually, others perceive him as the killer, and their expectations influence his self-identity, pushing him closer to becoming a real killer.

The Art of Disguise

Discovering his talent, Gary utilizes his academic knowledge of human psychology and behavior to create unique killer personas for each client.

From the stereotypical redneck military enthusiast and the thug covered in tattoos and scars, to the American Psycho and British psychopath, Gary dons masks that resonate with the client’s image of a hitman – whether from movies, news, or hip-hop music. This allows them to lower their guard, convinced that the stranger they just met is the right person to entrust with their murder plot.

Thus, a dialectical proposition about self-image emerges.

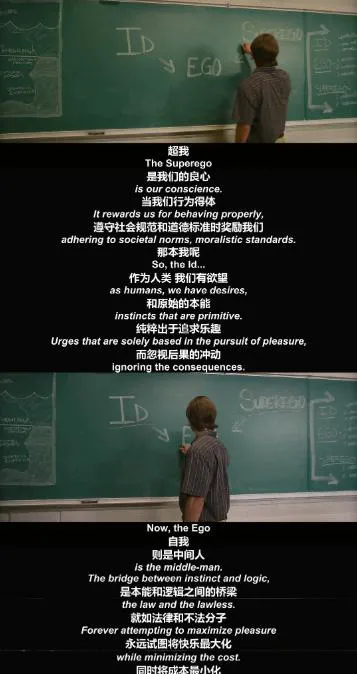

In his next class, Gary introduces Freud’s concepts of the id, ego, and superego.

Simultaneously, the film cross-cuts between his persona as the popular killer Madison and his ordinary professor appearance.

Nature vs. Nurture

In a stilted conversation between Gary and his ex-wife, the script somewhat deliberately raises the question of whether personality, as a stable and long-term psychological trait (such as the widely used Big Five personality traits based on scientific statistical foundations), can be altered through role-playing.

Interestingly, while Freud’s theory and the Big Five personality traits, seemingly at odds, presuppose a universal human nature (e.g., the id’s sexual drive and the Big Five categories), Jung’s theory, inherited from Nietzsche and Freud, and not explicitly mentioned in the film, may better align with the film’s ambiguous interpretation of role-playing and essence.

In fact, Nietzsche, quoted at the beginning of “Hit Man,” had a love-hate relationship with the concept of “masks.”

In his early work, Nietzsche praised how masks in ancient Greek drama allowed actors to forget their selves and humanity, and embody the Greek gods.

Later, he extended the concept of masks to criticize Western philosophers for donning masks of virtue and wisdom, concealing the chaotic, diverse, and complex qualities of human nature itself.

When Nietzsche wrote in “Beyond Good and Evil” that “every profound spirit needs a mask,” he was perhaps less concerned with praise or criticism, and more interested in clarifying why and how humans transform external projections into masks.

Because if humans understand life by constantly creating external images, and if “beneath the mask is another mask,” then boldly embracing every role and playing with every face is the path to becoming the master of one’s own life.

The Fusion of Selves

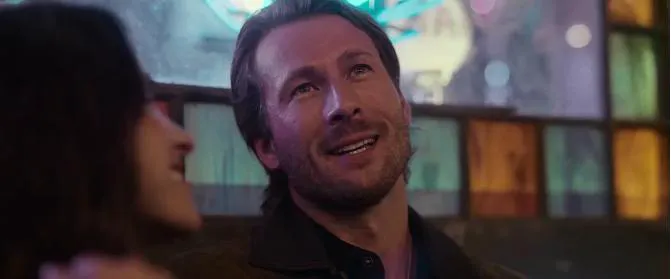

The tension between university professor Gary and the popular Madison ultimately doesn’t lead to the societal repression of desire, or confirm the immutability of human personality.

Instead, it evolves into a “hybrid” of Gary and Madison, intertwining the former’s rationality with the latter’s sensuality, allowing the mask to become ingrained in the flesh, becoming one.

A Romantic Comedy with Depth

Layered on top of this narrative core is a clever romantic comedy.

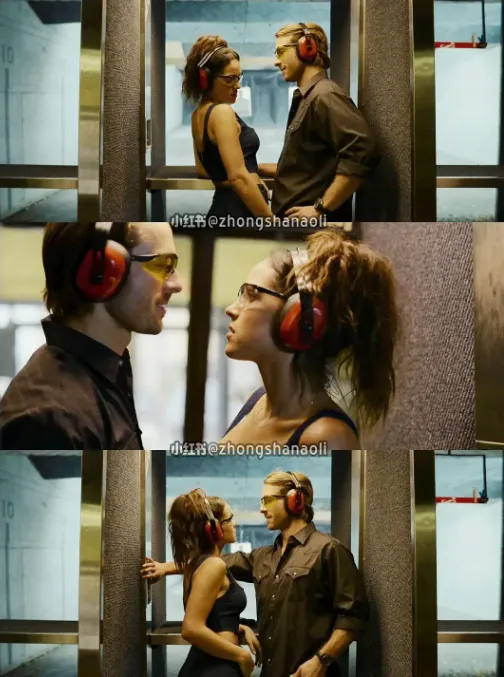

To rekindle his relationship with Madison, Gary must continue to meet her as the killer.

This persona is not only a charming, superego approved by mainstream tastes, but also an id driven by desire.

Returning to the conversation between Gary and his ex-wife, the latter urges him to change himself and find a partner.

Gary believes he can’t be in a normal relationship; but after meeting Madison, Gary changes himself for love, only to enter an abnormal relationship.

Linklater and Glen Powell have found the essence of the romance genre.

It’s a role-playing game akin to an undercover story.

To win someone’s heart, people invariably try to imagine their ideal partner, using that as a standard to adjust themselves, just as Gary tailors the ideal killer persona for each client.

Thus, the mask of a partner and the mask of a killer merge, even amplified by the sexual tension and excitement each possesses, sending the lovers’ adrenaline soaring, becoming increasingly addictive.

The Unmasking and Re-Masking

However, masks are eventually revealed.

A common romantic comedy trope is for the revelation of the mask to cause a brief separation, followed by a reconciliation after discovering that they love each other’s true inner essence, ending happily ever after.

But in “Hit Man,” the conflict of discovering each other’s true faces leads to them putting the masks back on: Madison is suspected by the police of shooting her ex-husband.

The police department sends Gary, disguised as the killer Madison, to probe for clues, forcing them to reprise roles that have already been exposed to each other, colluding to conceal the case and their relationship under police surveillance.

One person acting is deception, two people acting becomes a game.

As Gary and Madison share a higher level of knowledge than the other characters, their acting becomes a collaborative exchange of dialogue, smuggling secret messages within the lines, a form of intimate partner play. The superficial arguments and conflicts, because they are jointly orchestrated, can both vent their dissatisfaction with each other and achieve a cathartic release in the ensuing eye contact, even sparking more passion and excitement under the gaze (or rather, listening) of others.

While modern commercial films invariably pursue hybrid genres to expand their audience, “Hit Man” doesn’t forcibly insert romantic subplots, suspenseful elements, police shootouts, or car chases. Instead, it treats different genre logics as different modes of human behavior, finding the fundamental commonalities and tightly integrating them.

Echoes of Hitchcock

This “fictionalized” plot inevitably evokes Hitchcock’s classic “North by Northwest”: Roger is mistaken for Kaplan, then faces a series of chases, while the audience learns that Kaplan is a fictional character created for espionage; during his escape, Roger receives assistance from the beautiful double agent Eve Kendall, and to save her, Roger must play Kaplan…

Compared to “North by Northwest,” “Hit Man” also has brilliant plot twists, with the story capable of turning and turning again, a technique that is old-fashioned but never goes out of style in suspense films. In addition, the similar narrative techniques used in both films are noteworthy: letting the audience know (part of) the truth earlier than the characters, making the audience nervous or amused for the characters being kept in the dark. Suspense films don’t always need to keep the audience in the dark; sometimes, timely revelations can bring more interesting dramatic effects.

However, there are also important differences between the two films.

First, the fiction in this film has more depth, reflecting the struggle between self and id. Second, this film has no action scenes, but is constructed by dialogue, making it stylistically closer to the “Before” trilogy.

Let’s elaborate on these two aspects:

The Philosophy of Self

The film repeatedly mentions philosophical theories, all revolving around the concept of self. Gary introduces Freud’s ego and id in class, which also happen to be the names of his two cats. These concepts are used in a simple and understandable way to thread through these theories:

At the beginning, Gary talks about Nietzsche’s view of “taking risks in life,” which actually foreshadows the id; later, Gary and his ex-wife talk about the view that “the self is an illusion,” which, in my opinion, is close to Hume’s idea, and Gary wants to express that the self can make any changes.

He can become the way his ex-wife likes, but his ex-wife suggests that he talk to someone, not a therapist, but another woman.

This reflects Gary’s repression of the id: the self is an illusion, meaning that instincts can be modified, and he can cater to others’ expectations, constantly fabricating a better self. However, in this process, he actually stifles the id, and he needs to take risks in life to find the original power of life.

Interestingly, when Gary fabricates himself as Ron, he is not suppressing the self and becoming someone else, but releasing the id and becoming himself. This is why pretending to be someone else can sometimes help us find truth in false social interactions.

The Ron that Gary fabricates, or rather releases, is recognized by Madison, but Gary believes that Madison will not like the real him.

The confusion between “fabrication” and “release” is the challenge he faces: he thinks that Ron is fabricated by him, so Madison will not like him;

However, there is actually a real him in Ron, so Madison may also like him.

The process of recognizing this is the process of character growth, and also the process of reconciling the id and the self.

The Power of Dialogue

The film begins with philosophical dialogues in the classroom, and close-up shots of the speakers’ faces set the tone for the film’s style: the entire film has no action scenes, no bodies being shot, and all the murders only happen in imagination and language.

Instead, there is a lot of dialogue, with the camera switching between the speakers’ faces, simple and unadorned. The amazing thing is that there is almost no dull moment from beginning to end: the dialogue itself is witty and humorous, coupled with the constantly reversing plot, which makes people feel the expectation of “there seems to be another reversal here.” The description of the murder is full of details.

This is where the magic of language lies.

A good movie does not necessarily have to win with images. If it can create imagination, it can sometimes be more exciting than simple images.

Therefore, “Hit Man” has no gunfights or action scenes, but it has the most profound psychological depiction of an undercover killer; the film does not have the protracted separations and reunions between lovers, but accurately promotes the sublimation of the relationship in each short meeting. The killer and the love genre, as the mask and the flesh inside and out, truly achieve the overlapping and fusion of multiple genres, and reflect on the essence of the genre in the process, no longer just a commercially oriented genre assembly car.

A Moral Quandary

In the end, not only did the suspect really commit the crime, but even the fake killer really killed someone. But Linklater has no intention of delving into the inner struggles of the characters, nor does he want to provoke the audience and create unease. Instead, he uses a very persuasive foreshadowing to loosen the audience’s moral shackles, allowing people to truly understand the characters’ situation and enjoy the criminal thrill of the fugitive couple together.

Before the protagonist commits the crime, we see the “Madison-ized” sexy professor Gary in the classroom challenging the modern society’s abolition of the death penalty, reviewing the evolutionary value of exile and the death penalty in traditional tribes; in terms of character shaping, both Madison’s abusive ex-husband and Gary’s corrupt police colleagues are portrayed as scheming and toxic men, and getting rid of them is also benefiting society.

The above two seemingly understated crime plots are not superficial conservative treatments, because truly conservative creators will try their best to portray the protagonist’s helplessness when killing to establish a defensive legitimacy, or simply not let anyone die in a romantic comedy.

But in “Hit Man,” whether to kill or not has also become a moral and epistemological question with dialectical value, just as Gary said in the final exam class, as long as we maintain enough openness (which is also one of the five major personalities).

There is no standard answer in this world.

And becoming the person you identify with is the most important thing - whether this identity is a mask, a body, or a self.

Linklater’s Rebellious Spirit

If we revisit Linklater’s works, we can find that under those gentle and refined packages, there seems to be a rebellious spirit hidden: from the wandering hippies in the early works “Slacker” and “Dazed and Confused,” to the black elements in “Tape” and “Bernie,” and even the pioneering “Boyhood,” which sings the praises of youth growth over 12 years and rejects dramatic narratives, and the “Before” trilogy’s shift from romance to realistic concerns, all are unwilling to accept traditional types and narrative methods, and do not easily criticize the marginalized characters under the lens, but dare to challenge the moral norms of society.

Perhaps the real “Hit Man” is Linklater himself. He is sometimes as forgettable as Gary, and sometimes as sexy and charming as Madison; and under layers of masks, the only constant is the spirit of daring to try and take risks.