Between inspiration and outright folly lies a razor-thin margin, defined by a potent concept and a discerning artistic vision. “Apartment 7A” falters on both counts. Centered on Terry Gionoffrio (played by Julia Garner of “Ozark” fame), a minor character from the 1968 classic “Rosemary’s Baby,” whose fate is sealed from the original film’s opening credits, the premise itself is problematic. “Apartment 7A” seems to operate under the assumption that its audience is either unfamiliar with its source material or has conveniently forgotten its plot details.

Worse still, “Apartment 7A” fundamentally misunderstands the source of “Rosemary’s Baby’s” enduring and deeply unsettling power.

The Subtle Horror of “Rosemary’s Baby”

As one of the most celebrated American horror films ever made, “Rosemary’s Baby” isn’t “scary” in the modern sense, nor is it overtly horrific. Jump scares are virtually nonexistent, and truly frightening imagery is sparse, largely confined to a single mid-film hallucination sequence. Its horror exists at the periphery – lurking in the smiles of its protagonist’s overbearing neighbors, in the shadows of the New York apartment building, and even, quite literally, behind veils. It’s a horror film that, for much of its runtime, avoids showing the nightmarish elements of its story head-on. And when it does, it’s often with a gallows humor that only amplifies the true, outlandish evil of its antagonists.

“Apartment 7A”: Missing the Mark

“Apartment 7A,” conversely, can’t resist showing its hand. Built on static shots and sharp cuts, this prequel lacks the dreamlike control of its classic predecessor. It’s more direct, more outlandish, but devoid of “Rosemary’s Baby’s” sinister wit. In other words, “Apartment 7A” misses the mark because it misses the point.

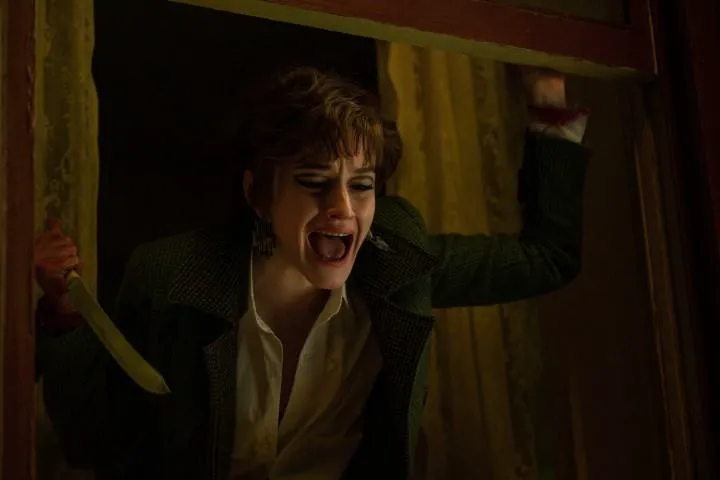

“Apartment 7A” begins with Julia Garner’s Terry as a New York dancer dreaming of seeing her name in lights. Set in 1965, the film swiftly dashes her aspirations. Its prologue quickly dispatches with Terry’s inability to dance after suffering a severe ankle sprain. This twist of fate sends Terry spiraling into a cycle of denial and substance abuse, culminating in her rescue from the sidewalk by Minnie (Dianne Wiest) and Roman Castevet (Kevin McNally), a seemingly kind elderly couple. Upon waking from a drug-induced stupor, Minnie and Roman invite her to stay in the apartment they own next to theirs and introduce her to their Broadway producer neighbor, Alan (a wasted Jim Sturgess).

What initially seems like a stroke of luck soon takes a sinister turn, with Terry experiencing unexplained bruises and increasingly demonic visions following a private evening with Alan. Minnie and Roman’s generosity morphs into something more sinister, and Terry soon grows fearful and suspicious of her neighbors’ secret (though not-so-secret) plans. Anyone familiar with “Rosemary’s Baby” knows what’s happening within the walls of the Bradford, the central building of “Apartment 7A,” and the prequel makes little attempt to deviate from the predictability of its premise. Instead, it nearly replicates the major dramatic beats of “Rosemary’s Baby,” making it feel more like a remake than a prequel, until the last moment when it is forced to diverge from its predecessor.

Overstating the Obvious

Director Natalie Erika James and her co-writers Christian White and Skylar James err by overemphasizing the malevolence of the Bradford’s residents, something “Rosemary’s Baby” only reveals explicitly in its third act. Minnie, in particular, is so overtly evil throughout “Apartment 7A” that Dianne Wiest’s performance fails to capture the unpredictable wickedness of Ruth Gordon, despite Wiest’s conscious, and distracting, attempts to mimic Gordon’s accent and cadence. Only Garner, the supremely talented young actress we now have, manages to emerge from the shadow of “Rosemary’s Baby” with something new and worthwhile. Her Terry is more forthright and desperate than Mia Farrow’s Rosemary, and Garner does her best to play her drama with sincerity and groundedness.

Missed Opportunities

While the decision to tell Terry’s story severely limits its freedom, “Apartment 7A” still stumbles upon unique ideas that connect closely to the core themes of “Rosemary’s Baby.” In its source material, Mia Farrow’s Rosemary believes that those around her actually see her as a person of flesh and blood. It’s only at the end that she realizes they see her and her body as a means to their own ends, and thanks to the immaculate beauty of Farrow’s performance, we feel both horror and grief on her behalf. In contrast, “Apartment 7A” uses Terry’s career as a vehicle to explore how women’s professional dreams have long been used as bargaining chips or tools for exploitation by figures of power (primarily men).

However, this truth is immediately apparent to both the audience and Garner’s Terry, meaning that the ending, which “Apartment 7A” executes with confidence, rings hollow. The prequel forgets the importance of “Rosemary’s Baby’s” supporting characters to its greatest moments and invests so little in how they treat Terry that their treatment doesn’t land with the weight it should. The new film is a stylish and, at times, genuinely frightening prequel, but it has so little new to say that its existence is difficult to justify.

The real-life actions of “Rosemary’s Baby” director Roman Polanski make appreciating the artistry of his earlier films and the overwhelming nature of the evil they highlight a difficult task. Had it better understood why the 1968 film was so disturbing, “Apartment 7A” might have served as an alternative for those unwilling to grapple with the complicated legacy of its predecessor. Instead, it mistakenly attempts to replace “Rosemary’s Baby’s” soft, suffocating touch with a more direct style that proves remarkably ineffective. Its horror is more obvious, its ideas more clunky. It hits you in the face, but it doesn’t get under your skin.