Decoding Arrival: A Missed Opportunity to Explore Language and Time

The film Arrival, adapted from Ted Chiang’s novella Story of Your Life, dares to tackle a subject often sidestepped in science fiction: the process of communication between humans and an alien civilization. This is arguably the most fundamental challenge any science fiction author dealing with extraterrestrial contact should address. Yet, many choose to avoid it for several reasons:

- The problem is inherently complex.

- Solving it requires delving into linguistics, a social science often perceived as less rigorous than the natural sciences.

- Exploring the topic can easily devolve into a dry, academic exercise, alienating a large portion of the audience.

However, some works do attempt to portray this challenging process. Robert Zemeckis’s Contact (1997) dedicates significant screen time to depicting human-alien communication. In the film, humans and the Vega aliens communicate through mathematics and logic. The director and writers skillfully build the process, starting with a sequence of prime numbers from space, progressing to Hitler’s television speeches, and culminating in complex coded texts. This approach transforms the film into a captivating puzzle, rewarding the audience with moments of intellectual satisfaction as the code is cracked.

The Courage to Adapt, the Failure to Execute

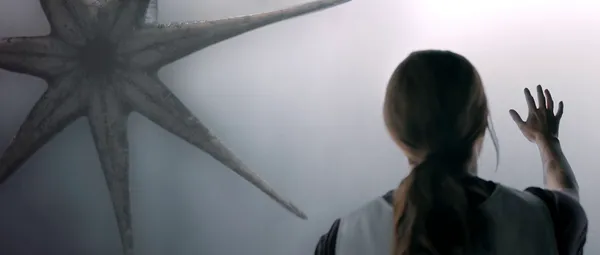

The producers of Arrival deserve credit for adapting Story of Your Life, a story that doesn’t easily lend itself to high-tension cinematic drama. However, it’s not impossible. In the novella, linguist Louise Banks’s journey to decipher the Heptapod language is structured in layers. She begins with their spoken language, then moves on to their written language, and finally, through the study of their writing, gains insight into their way of perceiving the world.

In academic research, the ascent from lower to higher levels is often the most thrilling part, akin to a goal in a soccer match. A skilled sports photographer would capture the passes, the dodges, and the jubilant reactions after the goal.

Arrival, however, fails to capture these moments effectively. The audience remains largely unaware of Banks’s intellectual breakthroughs, not through any fault of their own, but because the director doesn’t highlight them.

The Missing Piece: The Principle of Least Action

The film particularly falters in its handling of the principle of least action, a concept crucial to Banks’s epiphany. Perhaps this was done to simplify the film for a wider audience. However, without this and related explanations, viewers are left wondering how learning an alien script grants the ability to foresee the future.

In the original story, physicist Gary explains the principle of least action with a simple example: light, when refracted, always chooses the path of least time. This sounds strange, as it seems to attribute agency to light, implying it acts with a purpose. This is teleology, which describes the result of an event first. Science, however, typically describes the cause first, using a mechanistic approach. Whether we describe the cause or the result first is merely a difference in narrative order and doesn’t affect the event itself.

While it doesn’t affect the event, the way we speak reflects how we perceive the world. Ted Chiang suggests that humans typically perceive the world in a linear, cause-and-effect manner. This is debatable; many scholars argue that human thinking is inherently teleological, predisposing us to believe in religion rather than science.

However, let’s set aside this debate and accept Chiang’s premise: humans perceive the world from cause to effect. The Heptapods, on the other hand, perceive cause and effect simultaneously. Their writing, therefore, isn’t arranged linearly like human writing. Instead, it’s multi-dimensional, incorporating aspects like horizontal and vertical orientation, proportion, and curvature. The film simplifies this. Different narrative sequences are embedded in different dimensions.

However, the Heptapods’ spoken language can’t achieve the same multi-dimensionality as their writing because speech is bound by the linear nature of time. One can only utter one sound at a time. Thus, the Heptapods’ spoken and written languages are distinct systems, with the written language truly reflecting their thought processes.

Language Shapes Thought

In the 20th century, linguists Edward Sapir and Benjamin Lee Whorf proposed the theory of linguistic determinism, suggesting that language determines thought. They argued that language is not merely a mirror reflecting thought but also shapes the way we think.

For example, when we silently ponder something, a voice echoes in our minds. This is the result of linguistic habits permeating our thinking. A Chinese speaker hears a Chinese voice, while an English speaker hears an English voice. Interestingly, people who primarily use sign language experience not sounds but patterns of signing.

While Sapir and Whorf’s theory is somewhat radical and has faced criticism, it’s not entirely wrong. Since language at least influences thought, learning another language means learning another way of thinking. Banks, in learning the Heptapods’ written language, gradually adopts their way of thinking, perceiving the past, present, and future simultaneously.

The director fails to visually represent these theories in a compelling way. The film presents the process in a flat, uneventful manner. Each theoretical discovery is glossed over with calm dialogue. Eventually, the director seems to lose patience and uses a voiceover to quickly summarize the remaining theories from the original story, resulting in a film that induces drowsiness.

A Disrupted Narrative and a Lost Emotional Core

The director then attempts to salvage the film with a tacked-on ending, inexplicably having China declare war on the aliens, only for Banks to suddenly evolve and successfully prevent the military action. This disrupts the film’s narrative rhythm.

To make the declaration of war seem less abrupt—though it ultimately remains so—the director inserts a large amount of background information earlier in the film, leading to a second misstep. To make time for this exposition, the director sacrifices the narrative arc of Banks and her daughter, which is equally important to the alien storyline in the original story.

In Story of Your Life, the two storylines are interwoven in a balanced and artful way, a technique also used in Chiang’s Division by Zero. Why does the author favor intertwining a hard science fiction story with a poignant personal story? Most people assume that science appeals to reason and is therefore incompatible with emotion. In film, brilliant scientists are often portrayed as emotionally inept. Only a few can perceive the inherent harmony between science and emotion. The trajectory of an electron in a uniform electromagnetic field and the movements of an ice skater share the same poetry. Ted Chiang is undoubtedly one of those few who can see this connection.

The Paradox of Foreknowledge and the Power of Choice

Foreseeing the future and realizing the future is a classic paradox in mythology and science fiction. If someone foresees the future, they will want to avoid unpleasant events. But if they avoid the future, the prediction will not come true. One way to solve the paradox is to use an irresistible force to drag the seer into the future. Like Oedipus in Greek mythology, who wanted to escape his cursed fate but ultimately fell into the trap of fate.

Ted Chiang replaces fatalism with a sense of mission. He believes that when a person foresees the future, it inspires a sense of mission to fulfill their destiny. This fulfillment is Promethean. Prometheus, despite knowing he would be severely punished for stealing fire from the gods, was driven by compassion for humanity to bear the consequences.

Chiang combines this sense of mission with maternal love. Banks, through learning the Heptapod language, gains the power to foresee the future. She foresees that she will have a daughter and that her daughter will die prematurely. But maternal love leads her to accept this happy and unhappy fate. This great maternal love should have been the lyrical core of the film, but the director dilutes it.

Perhaps the director always intended to turn a novella that succeeds through its emotional depth and solid linguistic theory into a typical Hollywood blockbuster. This decision doomed Arrival to be a critical and commercial disappointment, because Story of Your Life simply lacks the elements needed to be a blockbuster.