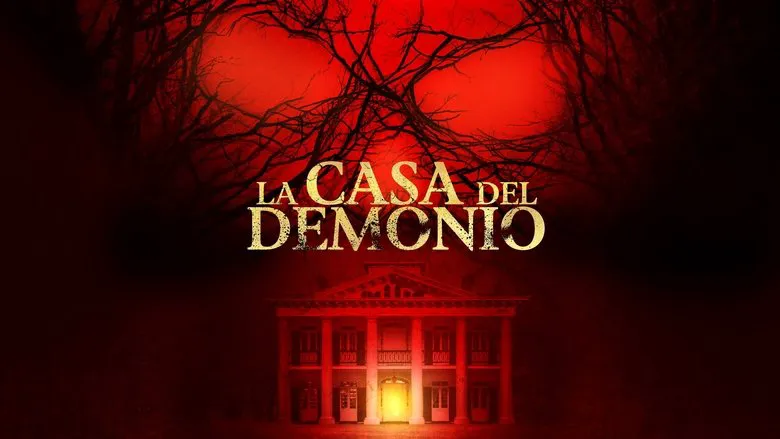

Behind the Shadows: The Filmmaking of Ti West’s “The House of the Devil”

Ti West’s The House of the Devil stands as a chilling testament to the power of atmospheric horror, a slow-burn masterpiece that meticulously builds dread rather than relying on cheap jump scares. Released in 2009, this film didn’t just tell a terrifying story; it immersed audiences in a bygone era of horror, paying direct homage to the genre’s golden age while crafting something refreshingly sinister. Let’s delve into what made this indie horror gem such a resonant experience.

The Auteur’s Vision: Ti West’s Homage to 80s Horror

Director Ti West made no secret of his admiration for late 70s and early 80s horror cinema. The House of the Devil is not merely inspired by films of that era; it consciously emulates their style, from its opening title cards to its grainy 16mm film stock, period-appropriate wardrobe, and synth-heavy score. West’s deliberate choice to shoot on film, rather than digital, immediately sets a retro tone, giving the viewer a sense of déjà vu, as if they’ve stumbled upon a forgotten VHS classic. This commitment to aesthetic authenticity wasn’t just a gimmick; it was fundamental to the film’s unsettling atmosphere, creating a subconscious familiarity that makes the eventual terror even more jarring. West’s meticulous direction ensured that every frame contributed to the mounting dread, a true exercise in patience that rewarded viewers with a suffocating sense of unease.

Crafting Claustrophobia: The Mansion as a Character

The Victorian mansion, where much of the film unfolds, is as much a character as Samantha herself. West and his production team masterfully utilized its labyrinthine corridors, dim lighting, and oppressive grandiosity to amplify Samantha’s isolation. The film’s description rightly notes that the house “appears to shift and twist at every turn, making it seem like a living being, closing in on her at every step.” This effect was meticulously achieved through production design and clever cinematography. Long, lingering shots explore the desolate rooms, allowing the audience to feel the suffocating emptiness alongside Samantha. The set dressings, including the unsettling symbols scratched into the walls, are subtle visual cues that hint at the sinister purpose of the Ulman family and the dark history of the house, slowly chipping away at Samantha’s composure and the audience’s sense of security.

The Power of Performance: Donahue and Noonan’s Eerie Chemistry

At the heart of the film’s effectiveness are the captivating performances of Jocelin Donahue as Samantha and Tom Noonan as Mr. Ulman (Belial). Donahue portrays Samantha with an admirable blend of vulnerability and resilience. Her initial desperation to earn money makes her relatable, allowing audiences to connect with her plight before the horror truly sets in. Her gradual descent from slight unease to abject terror is masterfully executed through subtle facial expressions and body language, conveying her internal struggle without relying on overt theatrics.

Noonan’s portrayal of Belial is equally chilling. His quiet, peculiar demeanor creates an aura of unsettling calm that is far more terrifying than outright menace. The film notes his “enigmatic behavior” and how his “unnerving presence seems to be seeping into her psyche.” This was a deliberate choice by West to make the character a walking embodiment of dread rather than a clear villain, leaving much to the audience’s imagination until the startling climax. The chemistry between these two actors, even in moments of quiet discomfort, is palpable, creating a tension that is almost unbearable.

A Masterclass in Slow Burn: Building Relentless Suspense

One of The House of the Devil’s defining characteristics is its slow, patient build. In an era dominated by rapid-fire scares, West deliberately embraces a “slow-burn” approach. The film spends its first act meticulously establishing Samantha’s predicament and the eerie atmosphere of the house, allowing dread to seep in through subtle details: the isolated location, the full lunar eclipse, peculiar phone conversations, and the shifting reality within the mansion. The “labyrinthine design,” “disturbing symbols,” and “inexplicable sense of malice” are introduced gradually, fueling Samantha’s (and the audience’s) growing apprehension. This unhurried pacing means that when the “unsettling events” finally unfold, and the “climax” arrives, the impact is devastating, earned through nearly an hour of sustained psychological tension. It’s a testament to West’s confidence in his craft and his understanding that true horror often lies in what is unseen or merely implied.

Ultimately, The House of the Devil is more than just a horror film; it’s a meticulously crafted experience that pays homage to cinematic history while forging its own unique path. Its technical craftsmanship, outstanding performances, and masterful suspense continue to captivate audiences and solidify its status as a significant entry in contemporary horror.