The Enigmatic Ballad of Limonov: A Portrait of a Rebel Artist

Eduard Limonov, or “Edichka” as he was known, was an odious poet who relentlessly pursued global recognition, traversing cities like Kharkiv, Moscow, New York, and Paris. Despite being born into a KGB family, Limonov, portrayed by Ben Whishaw, refused to collaborate with the authorities, instead taking on various jobs to make ends meet: factory work, serving as a butler, construction, and more. His life was dedicated to achieving international acclaim as a writer while staying true to his rebellious artistic spirit, resisting the temptation to commodify his image for marketing purposes.

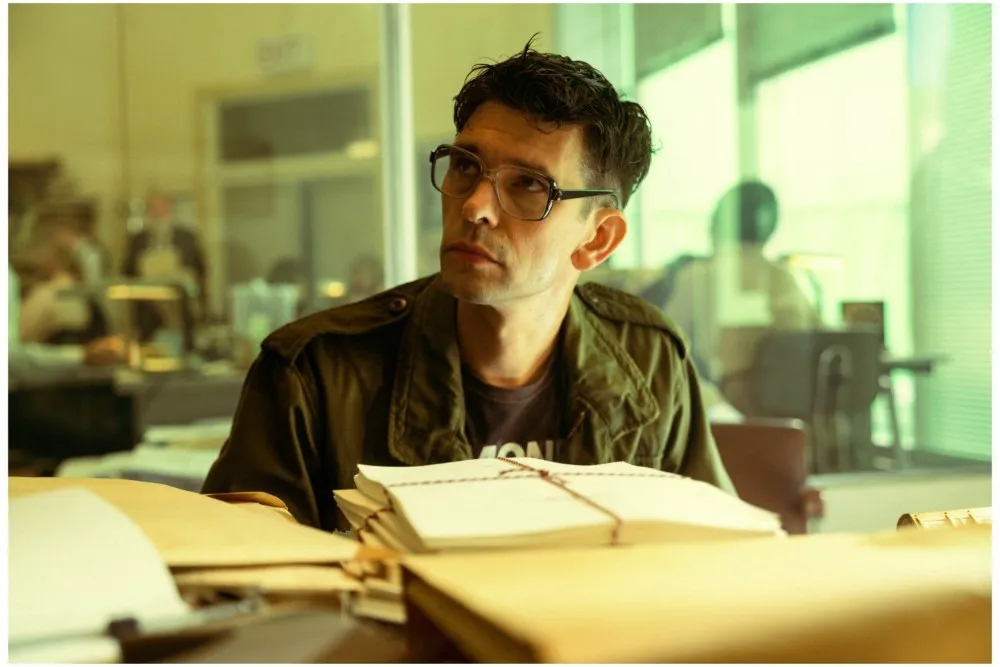

Ben Whishaw as Eduard Limonov in “Limonov: The Ballad of Eddie”

Director’s Lens: Biography and Interpretation

Interpreting a film solely through the lens of the director’s biography is an oversimplification. While parallels can be drawn between the lives of Eduard Limonov and Kirill Serebrennikov, the director of this biopic – exile, public recognition of provocative work, and conflicts with authorities – it’s crucial to acknowledge the significant differences. These range from the political climates of their respective countries to the personalities of the artists themselves. One spent decades seeking a publisher, largely in the underground, while the other has been embraced by elite circles both domestically and internationally. Therefore, it’s more insightful to examine the portrait of the artist that Serebrennikov, a director with a diverse portfolio spanning films, music videos, theater, and even exhibition curation, presents.

The Dichotomy of the Working Class Hero

In “Limonov: The Ballad of Eddie,” a significant portion of the film focuses on Limonov’s struggle to publish his work on his own terms and articulate his life philosophy. He consistently asserts his identity as a member of the working class, yet this crucial aspect of his biography receives limited attention in Serebrennikov’s film. Spanning over two hours, the film covers 30 years of the writer’s creative journey, resulting in a fast-paced narrative where the character is revealed through flamboyant scenes (such as cutting his wrists and smearing blood on the walls after a rejection) and self-assured pronouncements. However, Limonov’s frequent claims of marginality and counter-culturalism are not consistently supported by the plot or visual elements. In one scene, Limonov is compared to the Beat Generation, but writers like Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William Burroughs endured genuine hardship in Paris, surviving on meager funds and trading their work for squalid living conditions. In contrast, Serebrennikov’s characters navigate impeccably lit sets devoid of human presence, and the protagonist seems unfamiliar with the struggles of poverty.

Ben Whishaw as Eduard Limonov in “Limonov: The Ballad of Eddie”

Echoes of the Past: Style and Tone

Serebrennikov’s signature techniques – posters, inscriptions, animation, and music video inserts – are reminiscent of his earlier film about Viktor Tsoi, “Leto.” However, there’s a distinct difference in tone between the two biopics. In “Leto,” musical numbers and animation conveyed the fantastical world of the Leningrad rock scene, complemented by a constant sense of irony. In “Limonov,” Serebrennikov rarely allows himself to laugh at the protagonist. Ben Whishaw, who convincingly portrays the Russian accent without resorting to parody, may declaim his pride and adherence to principles, but fate repeatedly slaps him down, forcing him to clean up after the wealthy and obey the dictates of office managers.

A Romanticized “Genius”?

In Serebrennikov’s interpretation, Eduard Limonov appears as a man with delusions of grandeur, whose provocative behavior stemmed from a contempt for the world around him, a world that, of course, failed to understand him. This image of a smug and misunderstood “genius” is precisely the kind of romanticization and sensationalism that Limonov himself despised, and that Serebrennikov presumably rejects. The protagonist’s reflections on pandering to public taste can also be applied to Serebrennikov’s work, which seems to have abandoned formal experimentation in favor of a more familiar approach. The director seems aware of these creative compromises, as evidenced by the final monologue about the artist’s forced compliance with external rules, while conveniently omitting that his pursuit of scandalous fame is, in itself, a form of posturing.