A Misguided Film Despite a Talented Cast: A Review

Despite assembling a demonstrably talented cast, this film ultimately falters, succumbing to a narrative that feels both muddled and disappointingly underdeveloped. What could have been a profound exploration of human connection and the complexities of mental illness instead unfolds as a disjointed and poorly conceived cinematic endeavor. The film consistently misses opportunities to delve into the very depths its compelling true story offers, leaving viewers with a sense of unfulfilled potential.

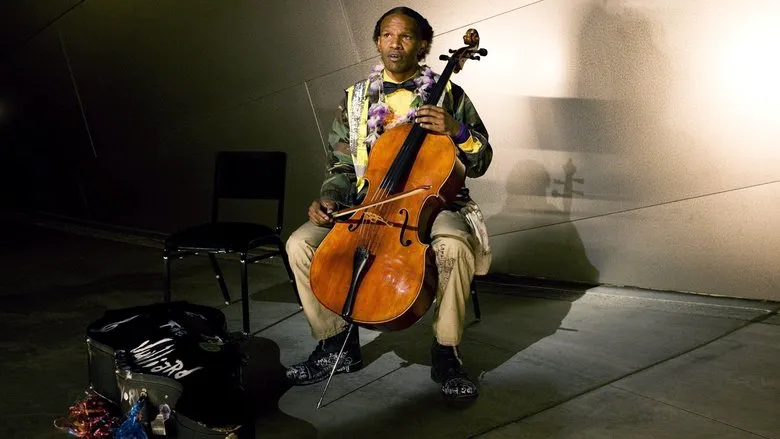

The core narrative follows a Los Angeles Times reporter who, during his daily rounds, stumbles upon a brilliant yet disheveled homeless musician. Intrigued by the man’s extraordinary talent and perplexing circumstances, the reporter decides to feature him in a series of articles, eventually compiling these pieces into a published book. This interaction forms the central axis of the film, charting the evolving relationship between the journalist and his enigmatic subject.

The Tragic Descent into Mental Illness

The troubled soul at the heart of this narrative is Nathaniel Ayers. In his formative years, Ayers was a beacon of light, brimming with infectious joy and possessing an almost spiritual devotion to music. His radiant smile and unbridled passion for performance painted a picture of a promising future, making his subsequent tragic decline into schizophrenia all the more heart-wrenching. As the insidious grip of the illness tightened, he began to experience debilitating auditory hallucinations, alienating himself from loved ones, abandoning his prestigious studies at the renowned Julliard School, and embracing a solitary existence on the streets. There, amidst the bustling backdrop of Los Angeles, he would engage in fervent conversations with unseen entities and offer impromptu Beethoven concerts to anyone within earshot, often oblivious to the bewildered and sometimes compassionate stares of passersby. His cello became both his burden and his sanctuary, a tangible link to the musical world he once inhabited.

A Reporter’s Compassionate Discovery

Nathaniel Ayers’ story, rooted in real-life events, carries profound weight. For a more romantic, perhaps Russian, audience, it might evoke parallels to Gumilev’s “The Magic Violin,” where majestic sounds draw forth spirits or wild creatures shadow the paths of musicians. However, Ayers’ destiny intersected not with mythical figures, but with Steve Lopez, a pragmatic, down-to-earth reporter. Lopez, with his keen journalistic eye, instinctively recognized the compelling and potentially transformative story embedded within the troubled homeless man’s plight. This discovery indeed proved to be a goldmine – metaphorically and literally. Lopez meticulously crafted numerous articles, which culminated in a best-selling book about Ayers. As expected, Hollywood was quick to acquire the lucrative film rights, and Joe Wright, lauded for his work on “Atonement,” was brought on board to helm the adaptation. From a filmmaking perspective, schizophrenia, with its inherent psychological complexities and dramatic potential, presents a rich canvas for exploration.

The Unconquered Challenge of Depicting Mental Illness

However, tackling a subject as nuanced and intricate as mental illness is akin to opening a Pandora’s Box; to effectively translate its complexities onto the screen, one must first be willing and able to genuinely delve into the profound depths of the protagonist’s mind and experience. Director Joe Wright, in this instance, appears to perpetually circle the subject, seemingly unsure of how to truly proceed or where to anchor his narrative. The central dilemma for the film seems to oscillate: should it focus on how the burgeoning friendship with the compassionate reporter miraculously healed the patient, transforming him into a fully functioning musical genius rescued from the streets? Yet, such a commercially driven narrative provides no genuine cure; the stark reality is that Nathaniel Ayers, despite now residing in secure housing, continues to play his cello on the very streets of Los Angeles, just as he always has.

Alternatively, should the film endeavor to courageously explore the convoluted and often terrifying inner world of a schizophrenic individual? Wright, regrettably, appears hesitant to commit, perhaps unwilling or unable to venture deepest into the dark and disorienting landscape of mental illness. This reluctance results in a portrayal that feels emotionally detached and intellectually superficial, preventing any meaningful insight into Ayers’ experience.

A Disappointing and Superficial Portrayal

This fundamental creative timidity culminates in a climactic scene that epitomizes the film’s shortcomings. As the mentally ill cellist listens intently to Beethoven’s powerful compositions, the screen explodes with a deluge of colorful, chaotic flashes and abstract light patterns. This simplistic, almost childish light show is ostensibly meant to serve as a visual representation, a fleeting glimpse into the patient’s complex and fragmented inner world. However, this shallow and ultimately unsatisfying portrayal serves only to highlight the director’s hesitancy, reducing profound psychological turmoil to a mere visual gimmick. It is a disappointingly superficial attempt to convey the depths of a condition that demands far greater empathy, insight, and artistic courage. The film, despite its promising premise and the inherent drama of the true story, ultimately fails to deliver a meaningful exploration, leaving its audience with a sense of what could have been.