The Black Phone: When the Past Calls with Terror

Joe Hill, son of Stephen King, has long established a reputation independent of his father in the literary world and its adjacent screen adaptations. While remaining a spiritual and ideological heir to the King of Horror, Hill has found his own voice and built his own universe of fear. “The Black Phone,” one of his most acclaimed short stories, fell into the hands of Scott Derrickson, a director known for the first “Doctor Strange,” but beloved by genre fans for “Sinister.” This collaboration was a labor of love: “The Black Phone” is one of the most thoughtful and complete projects from Blumhouse (the studio behind “Insidious” and “The Purge”) in recent years.

The late 1970s. Anxiety hangs over a one-story town, where every lamppost is “decorated” with an announcement: “Missing Child.” Locals, swallowing the lump in their throats, glance at each other and the new name printed in bold, but continue to pretend that life goes on. Brother and sister, Finney (Mason Thames) and Gwen (Madeleine McGraw), go to school, collecting bruises from local bullies, and at home, beatings from their alcoholic father. Domestic violence is the climate of every day, which can end in disappearance: no black eye can compare to the grip of the Grabber, which Finn is destined to experience on his wrist.

Mason Thames as Finn in a still from “The Black Phone”

“The Black Phone” offers a walk through familiar territory, where every corner feels like home: filmstrips in class, school bathrooms as the main arena for showdowns, arcade games after school, and launching rockets in the backyard. But the artifacts of memory that fill the screen are not marked with bright spots of nostalgia, as “Stranger Things” dictates, but with warning signs of imminent threat. The very America that pop culture of the 2020s misses so much is a zone where there is no safe place.

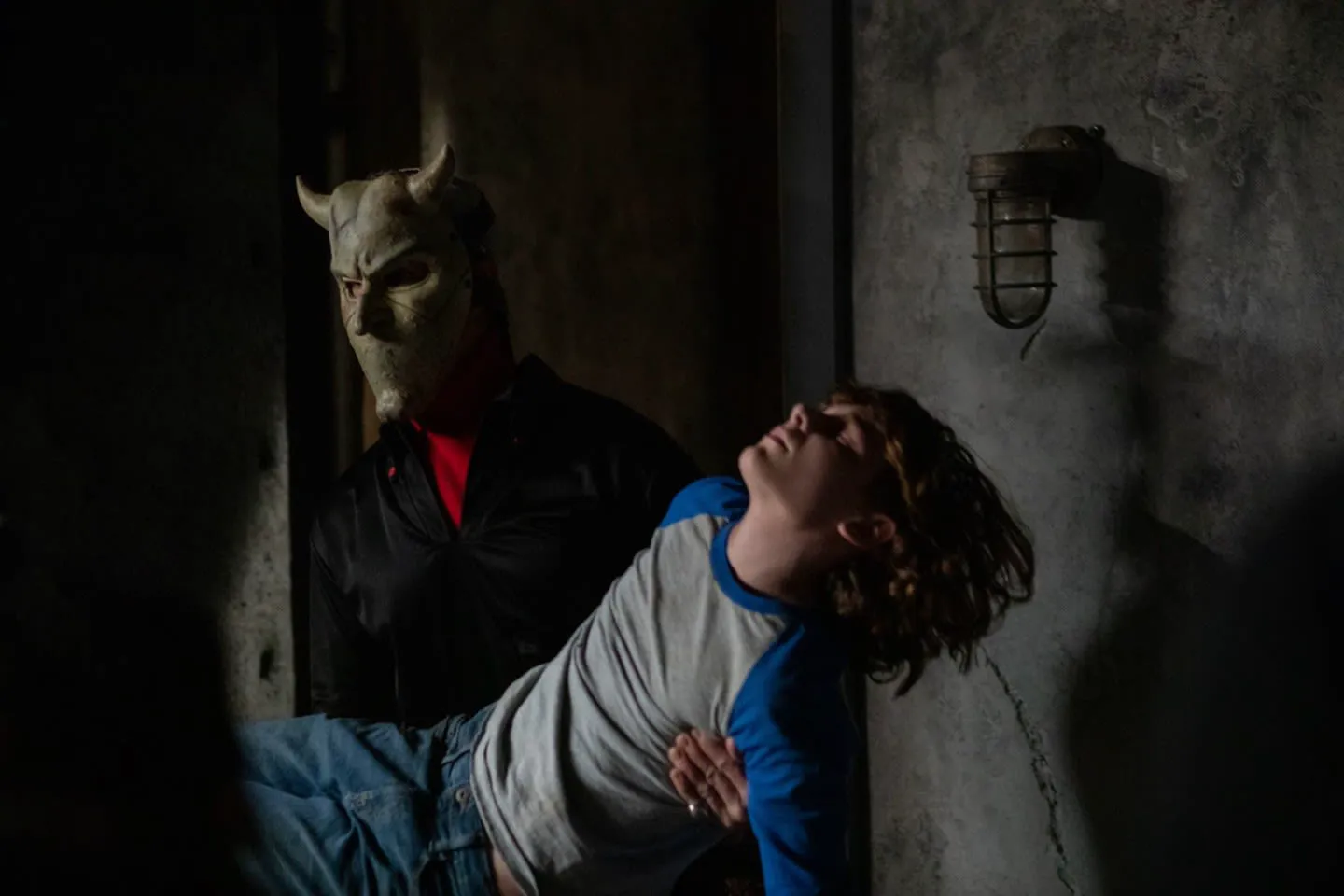

Ethan Hawke as The Grabber in a still from “The Black Phone”

Genre master Scott Derrickson does not reproduce the feeling of a nightmare, but constructs a constant anxiety, a feeling when you feel sick to your stomach from every evening phone call—the voice on the other end is ready to announce that your best friend has not returned home. As always happens with the indifference of adults, the miracle of salvation is in the hands of children: Gwen dreams of fragments of her classmates’ executions, and Finney, locked in the ill-fated basement, receives calls from the boys who could not escape—the youngsters want to help so much that they are ready to connect from the afterlife. Derrickson’s mysticism is not a genre convention, but a form of tragedy and a tool for empathy: if only the newspaper delivery boy could speak.

Echoes of “It” and a Shift in Perspective

The comparison with “It” is inevitable, both in plot and style: as a child, Hill was afraid of his father’s book, Tommy Lee Wallace’s TV movie, and the real serial killer John Wayne Gacy, and therefore the Grabber in the story was a clown. In the film adaptation, however, Derrickson and his constant colleague-screenwriter C. Robert Cargill turned “Doctor Strange”—the previous item in their shared filmography—inside out, changing the maniac’s profession. Yesterday’s magician was a hero, and today’s magician has become the most terrible enemy.

Madeleine McGraw as Gwen in a still from “The Black Phone”

But what matters is not that the circus is a den of not only joy, but the chosen angle of view. The main lever of “The Phone” is Ethan Hawke in a satanic mask with horns: a kind of avatar of the nightmare living in every basement that is locked. But, unlike Andy Muschietti (the “It” diology), Derrickson does not enjoy the antagonist, does not poeticize violence, and does not put the maniac on the altar of pop-cultural sacralization of evil. Ethan Hawke’s face is hidden under a mask, and flashbacks of the Grabber’s backstory and the contours of death rituals do not spread across the screen. The viewer sees the killer through the optics of a frightened child, and the timing for revealing the motivation and admiring the tricks of the inflamed brain is given to the victims of the maniac.

Mason Thames as Finn in a still from “The Black Phone”

A Symphony of Small Tragedies

The shift in focus makes you cry during the viewing, not be afraid of every otherworldly call. The dead children do not remember themselves, becoming another number in the list of victims, a statistic, a line of accusation in the protocol, and a headline in the morning newspaper. Finn calls each boy by name, sculpting the individuality of the dead from fragments of memories—one grief of an entire city is divided into many small tragedies in one-story houses. The reverent attitude to the dead completely changes the matter of the frame, leading the film away from similar films.

If desired, “The Black Phone” can be recommended as a successful genre film in a retro frame. Bicycles, talk about Bruce Lee and “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” a notable cameo by James Ranson (Eddie from “It: Chapter Two”): Derrickson successfully scares with the editing of the chronicle and unnatural curves of bodies according to the precepts of “Sinister,” and Ethan Hawke at one point becomes a disgusting bad guy. But it is worth taking a step back and looking at the everyday landscape of the late 70s as a whole, as the indifference and homelessness of those who will never grow older chills you to the bone.