Joe Hill’s Legacy: “The Black Phone” and the Anatomy of Fear

Joe Hill, son of Stephen King, has long established himself as a literary force, carving a niche in the world of adaptations. While inheriting the mantle of the King of Horror, Hill has cultivated his unique voice and built his universe of dread. “The Black Phone,” one of his most acclaimed short stories, found its way to Scott Derrickson, director of the first “Doctor Strange” and genre fans’ darling for “Sinister.” This collaboration was a match made in heaven, resulting in “The Black Phone,” one of Blumhouse’s most thoughtful and cohesive projects in recent years.

A Town Gripped by Fear

The late 1970s. A sense of unease hangs over a small, single-story town, where every lamppost is “decorated” with a missing child poster. Locals, swallowing the lump in their throats, eye each other and the latest name printed in bold, but they carry on as if life goes on. Siblings Finney (Mason Thames) and Gwen (Madeleine McGraw) attend school, enduring the taunts of bullies, and at home, the abuse of their alcoholic father. Domestic violence is the norm, a daily climate that can end in disappearance. No bruise under the eye can compare to the Grabber’s grip, which Finn is destined to experience on his wrist.

Mason Thames as Finn in a still from “The Black Phone”

“The Black Phone” invites us to familiar territory, where every corner feels like home: filmstrips in class, school bathrooms as the main arena for fights, arcades after school, and launching rockets in the backyard. But the artifacts of memory that fill the screen are not marked with the bright spots of nostalgia, as in “Stranger Things,” but with warning signs of impending doom. This America, so yearned for by 2020s pop culture, is a zone where there is no safe place.

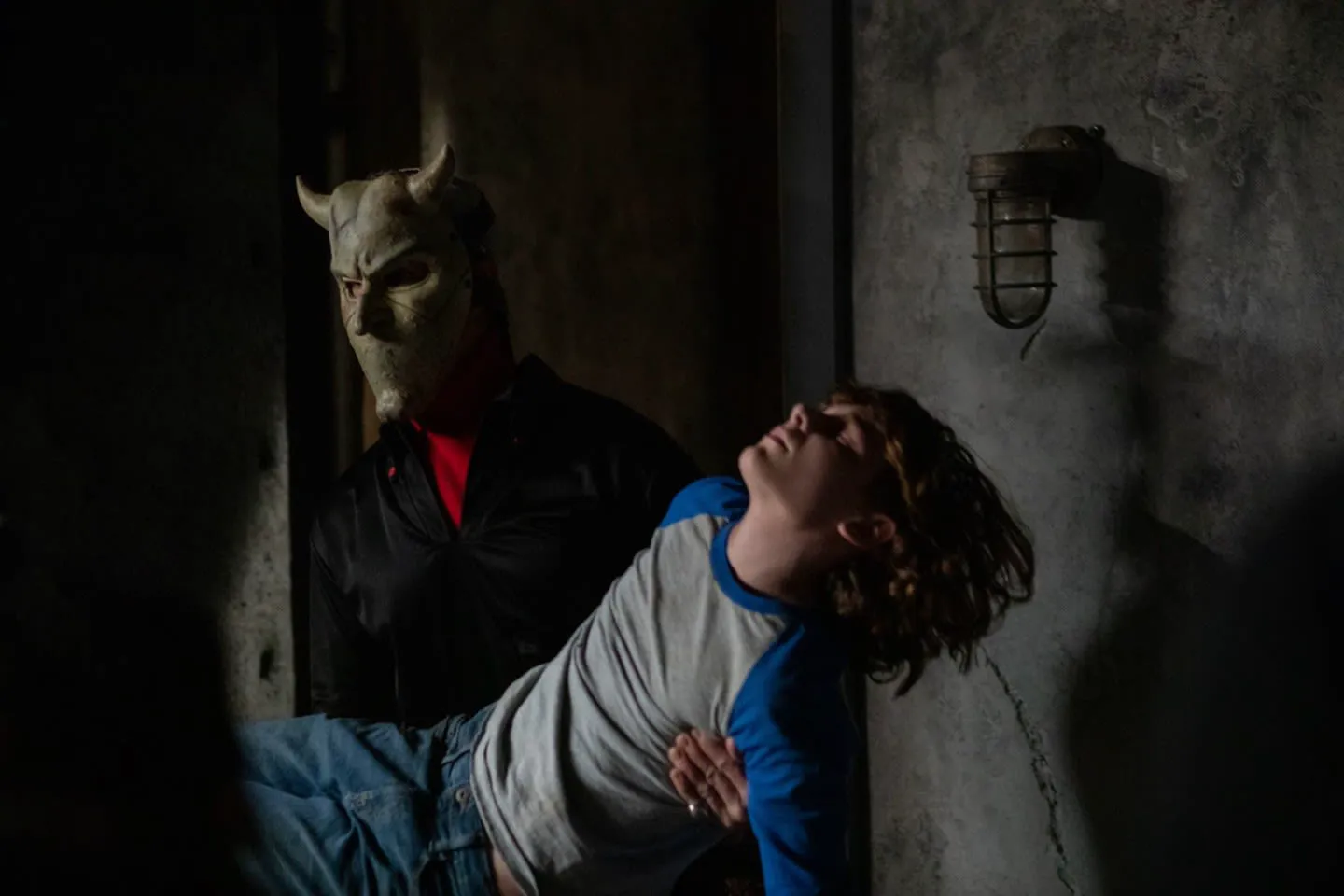

Ethan Hawke as The Grabber in a still from “The Black Phone”

The Power of Children

Genre master Scott Derrickson doesn’t recreate the feeling of a nightmare but constructs a constant anxiety, the feeling of dread with every evening phone call – the voice on the line ready to announce that a best friend hasn’t come home. As always, with adult indifference, salvation lies in the hands of children: Gwen dreams of snippets of her classmates’ executions, and Finney, locked in the ill-fated basement, receives calls from the boys who couldn’t escape – young souls so eager to help that they are willing to connect from beyond the grave. Derrickson’s mysticism is not a genre convention but a form of tragedy and a tool for empathy: if only the paperboy could speak.

Echoes of “It”

Comparisons to “It” are inevitable, both in plot and style: as a child, Hill feared both his father’s book and Tommy Lee Wallace’s TV movie, as well as the real serial killer John Wayne Gacy, so in the story, the Grabber was a clown. In the adaptation, Derrickson and his longtime screenwriter C. Robert Cargill turned “Doctor Strange” – their previous joint filmography entry – inside out, changing the maniac’s profession. Yesterday’s magician was a hero, and today’s illusionist has become the most terrifying enemy.

Madeleine McGraw as Gwen in a still from “The Black Phone”

But what matters is not that the circus is not only a haven of joy but the chosen angle of vision. The main lever of “The Black Phone” is Ethan Hawke in a satanic horned mask: a peculiar avatar of the nightmare living in every locked basement. But, unlike Andy Muschietti (the “It” duology), Derrickson doesn’t revel in the antagonist, doesn’t poeticize violence, and doesn’t place the maniac on the altar of pop-cultural sacralization of evil. Ethan Hawke’s face is hidden under a mask, and flashbacks of the Grabber’s backstory and outlines of death rituals don’t litter the screen. The viewer sees the killer through the lens of a frightened child, and the runtime for revealing motivation and admiring the tricks of an inflamed brain is given to the maniac’s victims.

Mason Thames as Finn in a still from “The Black Phone”

Shifting the Focus

This shift in focus makes you cry during the viewing, not fear, with every otherworldly call. The deceased children don’t remember themselves, becoming just another number on the list of victims, a statistic, a line of accusation in the protocol, and a headline in the morning newspaper. Finn calls each boy by name, sculpting the individuality of the dead from fragments of memories – one grief of an entire town is divided into many small tragedies in single-story houses. This reverent attitude towards the deceased completely changes the fabric of the frame, leading the film away from similar works.

If desired, “The Black Phone” can be recommended as a successful genre film in a retro frame. Bicycles, talk of Bruce Lee and “The Texas Chainsaw Massacre,” a notable cameo by James Ranson (Eddie from “It Chapter Two”): Derrickson successfully scares with the editing of the chronicle and unnatural contortions of bodies in the spirit of “Sinister,” and Ethan Hawke instantly becomes a repulsive bad guy. But take a step back and look at the everyday landscape of the late 70s as a whole, and you’re chilled by the indifference and homelessness of those who will never grow older.