Ashes of Time: A Wong Kar-wai Take on Wuxia

Unlike the Zen-infused narratives of King Hu’s later wuxia films, the fantastical elements of Tsui Hark’s, or the Taoist philosophy of Ang Lee’s Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Wong Kar-wai’s Ashes of Time can only be meaningfully compared to his later work, The Grandmaster, within the context of the wuxia genre.

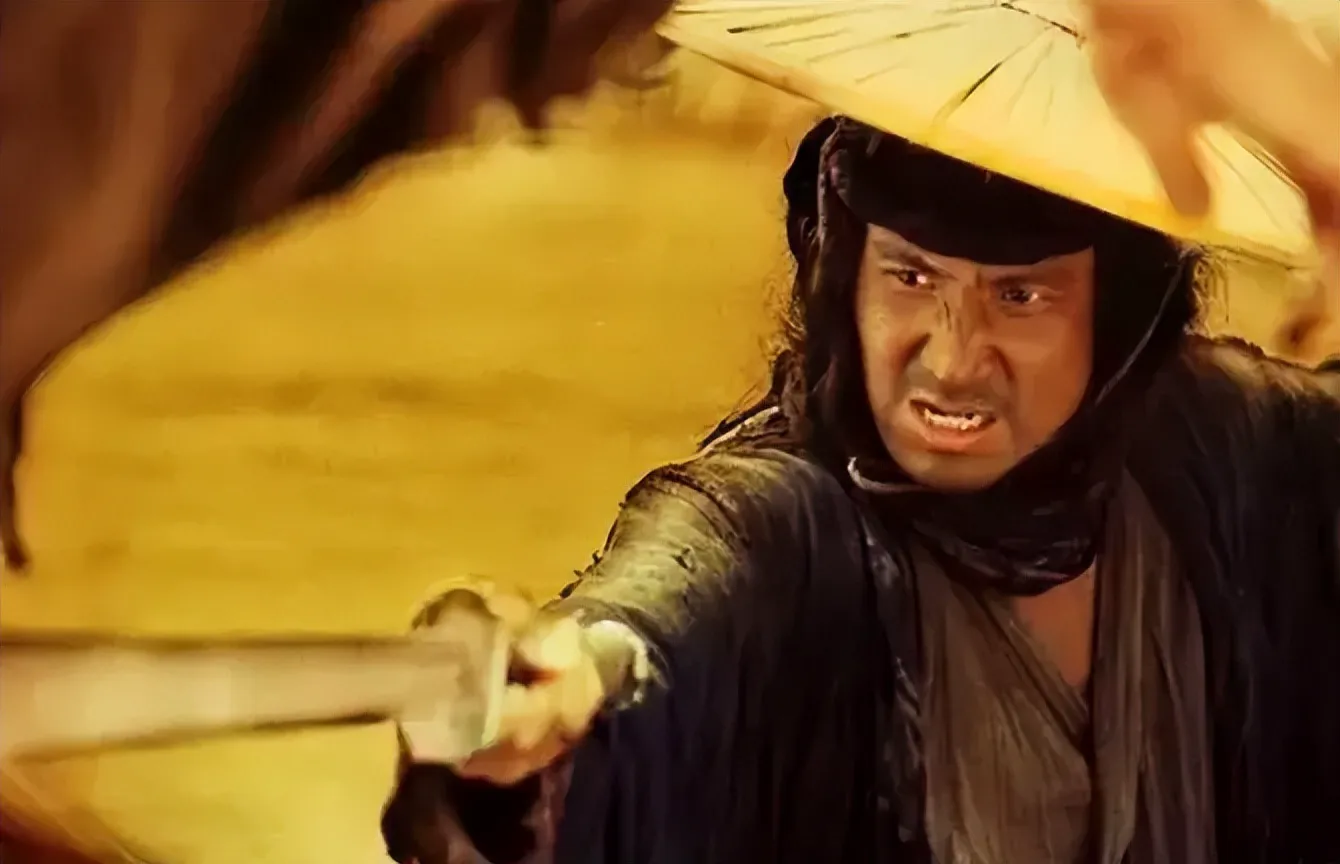

Ashes of Time (1994)

Specifically, the martial arts world in Ashes of Time serves merely as the narrative backdrop for “a story of a half-life romance” (as Wong Kar-wai himself described it). In contrast, The Grandmaster brings the “lost world of martial arts” to the forefront.

The Brevity of Combat in Ashes of Time

In Ashes of Time, all the martial arts are reduced to “one-cut style,” so swift that the audience barely registers the characters’ moves before the fight concludes.

Wong Kar-wai employed long takes for scenes like Ouyang Feng’s encounters with Hong Qi. Reportedly costing HK$1.5 million, these fight scenes were strategically placed at the beginning and end of the film by Wong and editor Patrick Tam. In Ashes of Time, the action sequences function as mere bridges, lacking narrative drive.

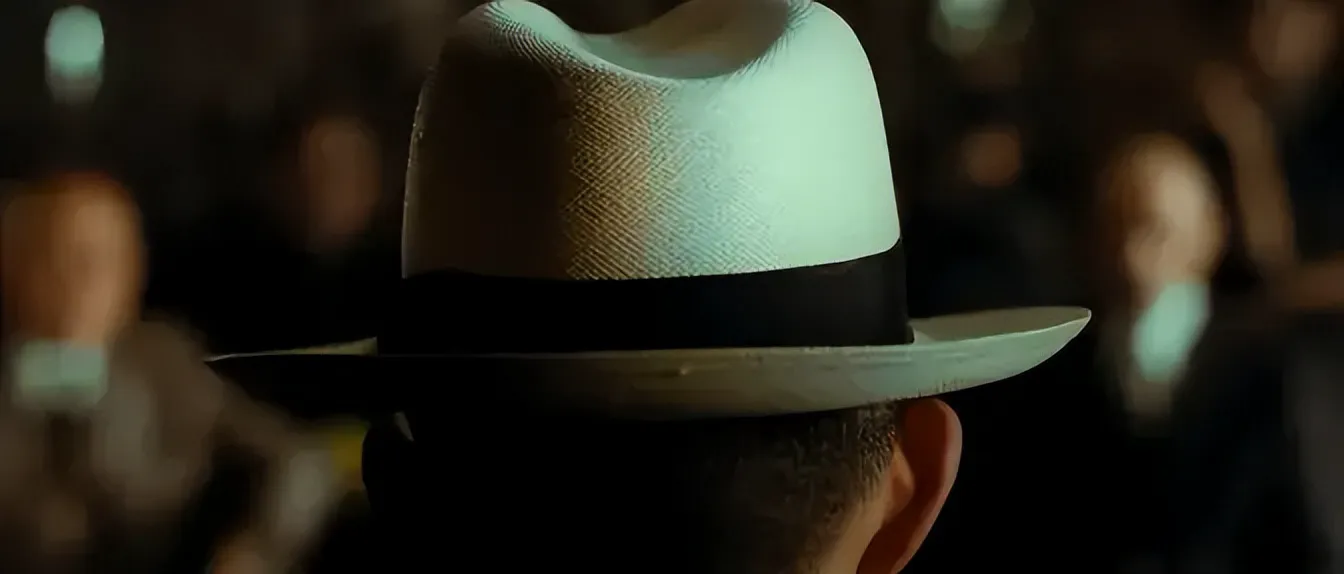

The Art of Combat in The Grandmaster

Conversely, in The Grandmaster, Wong Kar-wai utilizes high-speed photography and constructive editing to amplify the “grandmasters’” techniques. From the initial stance to the secret moves, the engagement, and the final pose, every detail is meticulously crafted. Wong treats these fight scenes as cultural heritage. More importantly, the fights between Ip Man and Er’niang, and Er’niang and Ma San, are fully integrated with character arcs and narrative tension.

The Grandmaster (2013)

The Dual Production: Ashes of Time and Eagle Shooting Heroes

In December 1992, Wong Kar-wai brought a group of Hong Kong stars to Yulin, Shaanxi, to begin filming Ashes of Time. Due to slow progress and budget overruns, Jet Tone Production decided to shoot a low-budget comedy, Eagle Shooting Heroes, which was completed in just 27 days.

Jeffrey Lau, the director of Eagle Shooting Heroes and a friend of Wong Kar-wai, joked, “They filmed Ashes in the morning and Heroes in the afternoon. They were on the verge of a mental breakdown. Shooting Ashes of Time was as painful as losing a family member, while returning to Eagle Shooting Heroes was as joyful as having a newborn.”

Eagle Shooting Heroes (1993)

This explains why Joey Wong’s scenes were almost entirely cut from Ashes of Time. Brigitte Lin also only filmed half the movie because she had to shoot other projects. Wong Kar-wai turned these transient actors into passersby at the “Western Poison Inn.” Only Leslie Cheung could focus on one film at a time (and was the last to leave the set).

The “Bourgeois” Touch in Ashes of Time

Importantly, none of the heroes in Ashes of Time are traditional heroes, loyal and righteous, ready to help those in need. They are imbued with the “bourgeois” sentimentality of Wong Kar-wai’s urban films. These love-stricken heroes revolve around Western Poison, coming and going. In this sense, Ashes of Time is a wuxia film with Wong Kar-wai’s early style.

The only character with the traditional chivalrous spirit is Hong Qi, and he is righteous only because he doesn’t want to become like Western Poison. Thus, this film, adapted from Jin Yong’s wuxia novel, is stripped of its history, its characters (only retaining some names from the original novel), and its traditional chivalry. In Wong Kar-wai’s words, “Ashes of Time is about a dual contrast of ‘rejection’ and ‘being rejected,’ ‘escape’ and ‘return.’” As an anti-traditional wuxia film, Ashes of Time has no outward centrifugal force, only an inward centripetal force.

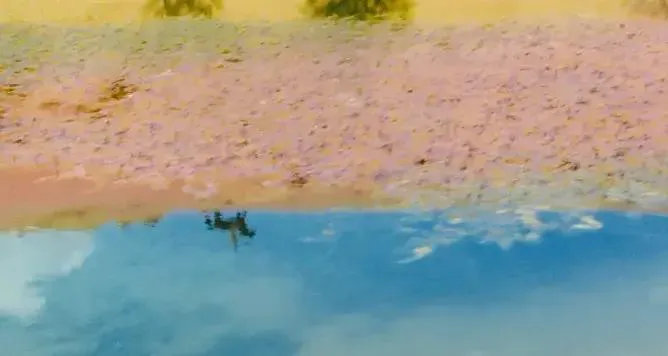

Wong Kar-wai uses extensive character monologues and slow horizontal pans (focusing only on their faces as they move) to “write” the characters’ inner secrets. In contrast, the martial world (a closed space, unlike the open space of The Grandmaster) and traditional chivalry become illusory. In this sense, Wong Kar-wai replaces the chivalrous spirit in Ashes of Time with a sense of “nostalgia.” All the characters in the film are wandering, unable to return “home.” Returning home, or “turning back,” becomes the central theme of the film.

The Theme of “Turning Back”

Speaking of the motif of “turning back,” The Grandmaster continues the seed planted by Wong Kar-wai in Ashes of Time. Back then, Wong Kar-wai and Sammo Hung were scouting locations together. Sammo Hung, being overweight, quickly became unable to climb and said, “Do you think there’s anything behind the mountain? It’s just the same desert, another mountain. Don’t climb!”

Said in jest, but heard with intent. Wong Kar-wai transformed this sentence into Western Poison’s line, “Everyone goes through this stage, seeing a mountain and wanting to know what’s behind it. Actually, it might just be another mountain. ‘Turning back’ might be better… I know that if you don’t want to be rejected, the best way is to reject others first. For this reason, I have never ‘gone back.’ Actually, it’s pretty good over there, but unfortunately, I can’t ‘turn back’ anymore.”

Looking at the core theme of The Grandmaster, “The old ape hangs its seal and looks back, the key is not in hanging the seal, but in looking back” (Gong Baosen’s words), Ashes of Time and The Grandmaster become two mirror images of each other, with The Grandmaster being an imitation and rebuttal of Ashes of Time.

The Theme of “Rejection”

Regarding “rejection,” it is explicitly stated in Western Poison’s line, “If you don’t want to be rejected, the best way is to reject others first.” Because his true feelings were rejected by his sister-in-law, Ouyang Feng confines himself to the inn. Thus, the film’s theme is linked to its spatial arrangement. Murong Yan/Murong Yan, the wandering swordsman, Hong Qi, and Eastern Heretic become Western Poison’s passersby.

As mentioned earlier, to avoid becoming “Western Poison,” Hong Qi chooses to “move forward.” He avenges the egg-selling woman, he travels the world with his wife, and he uses Western Poison’s words to mock him: “Who says you can’t travel the world with your wife!” Of course, this sentence more directly satirizes the lone heroes in traditional wuxia films. In the end, Western Poison burns down the inn, destroying that past and memory.

Also regarding “rejection,” implicitly, Wong Kar-wai turns the inn into a “dressing room” where time and space intersect, like the room where Madeleine (Kim Novak) “changes clothes” in Hitchcock’s Vertigo. Hitchcock uses rotating shots to reverse time and identity. Wong Kar-wai uses deep focus shots (minute 27) and alternating editing (minute 32 and minute 91) to reverse time and identity.

First, consider the deep focus shot. “That night was particularly long. Because I seemed to be talking to two people at the same time. Later, I couldn’t tell if she was Murong Yan or Murong Yan.” The pitch-black depth of field becomes a time tunnel, and Western Poison, standing in the depth of field, changes into another person—Eastern Heretic, saying, “It’s you!” In this narrative segment, the camera remains fixed (except for a few establishing shots inserted in between), and the time and identity of Western Poison (Eastern Heretic) and Murong Yan seem to be reversed in the dark depth of field tunnel.

Next, consider the alternating editing. Eastern Heretic, Murong Yan, Western Poison, and the sister-in-law embrace each other, searching for “another person” in each other’s bodies. Conversely, they consciously treat themselves as “another person.” The substitution of identities, the light and shadows climbing on the walls, in Frankie Chan’s score, and in the “click” of the editing, are reversed.

The Structure of the Film

Finally, regarding the structure of the film, in Wong Kar-wai’s words, "Ashes of Time is a very tightly structured film. When re-editing it (referring to the later ‘Ultimate Cut’), giving up anything would break its balance because there are many scenes put together. I used the Chinese almanac to make a structure, which is a very tight structure, not freehand.

Chungking Express is freehand, we go wherever we go, we shoot wherever we shoot." The Chinese almanac—time—to put it simply, Ashes of Time is like a small boat drifting in the river of time. Time is structure; time is also ashes. In the last scene, Maggie Cheung, in a frame-within-a-frame composition, stands alone, reciting, “I always thought I had won, until one day I looked in the mirror and realized I had lost. In my best time, the people I loved the most were not by my side. If time could ‘turn back,’ how great would that be.”

Here, Maggie Cheung’s last line, “turn back,” forms a subtle mirror effect with the linear time constructed by the “time nodes” (Chinese almanac) throughout the film. We know that the solar terms in the Chinese almanac occur every year, and this cyclical “circular structure” is actually linear and even cruel.

Another detail worth noting is that Wong Kar-wai uses the scene of “Western Poison doing business” in both the beginning and the end of the film (minute 4, minute 92)—“Brother, it seems you are also in your forties. In these forty years, there are always some things you don’t want to mention again, or some people you don’t want to see again…” These two repeated narrative segments not only create a circular structure—echoing the Chinese almanac—but also generate a sense of desolation in this repetition.

Everything corresponds to Wong Kar-wai’s director’s interpretation of this film: “In this martial world, the most powerful thing is not martial arts, but time.” Some people, some things, once missed, can never be turned back. Those emotions that permeate the past can only slowly cool down and become “ashes of time.”