The Enduring Legacy of “Psycho”: More Than Just a Shower Scene

Talk to film critics familiar with psychoanalysis about “Psycho,” and they’ll tell you how perfectly the film embodies the perverse pleasures of cinema. Chat with horror aficionados, and they’ll explain how the movie marked a turning point, shifting the genre’s focus from external threats to the terrors within our own minds.

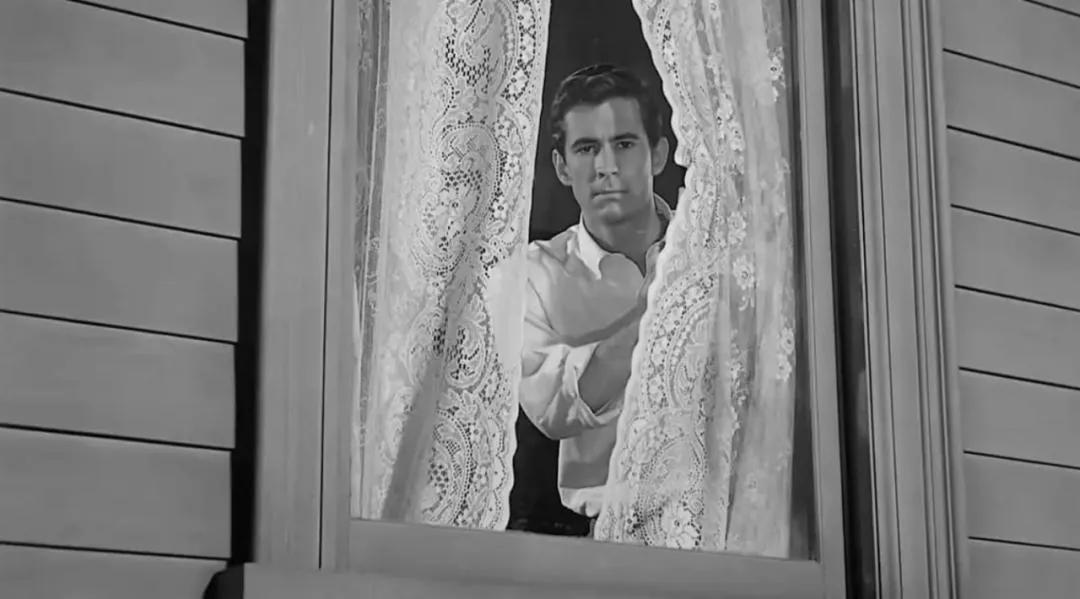

“Psycho” (1960)

However, if you speak with anyone who actually saw “Psycho” in a movie theater back in 1960, they’ll likely recount the sheer terror they experienced. I vividly remember a Saturday matinee where my two girlfriends and I spent most of the film with our eyes tightly shut, relying on the soundtrack and the screams of the audience to gauge when it might be safe to peek at the screen again, drawn by a morbid curiosity to the unfolding horror.

A Shared Cinematic Trauma

Most people who saw “Psycho” during its initial theatrical run have similar, deeply ingrained memories. Many recall the shock of the infamous bathroom murder and the subsequent months, or even years, during which they avoided taking showers. But while the film’s impact on the nation’s bathing habits is well-documented, its fundamental transformation of the moviegoing experience is less often discussed.

With its deliberate, voyeuristic shots of Marion Crane’s affair and the theft of $40,000, culminating in the dizzying, spiraling descent of the bathroom murder scene “flushing” into the drain, “Psycho” encouraged viewers to relinquish the control they had been conditioned to expect from classical cinema. With “Psycho,” film, in a way, reverted to what critic Tom Gunning described as the “attractions” of pre-classical cinema – an experience more akin to a rollercoaster ride than an engagement with a classical narrative.

The Rollercoaster Ride of Modern Cinema

Anyone who has watched movies in the last two decades will recognize how deeply ingrained this rollercoaster-like experience of tension and release, attack and escape, has become. While narrative hasn’t been abandoned, it’s often superseded by a barrage of audiovisual shocks and thrills, as Thomas Schatz noted in “The New Hollywood”: “sensory, dynamic, fast-paced, increasingly reliant on special effects, increasingly ‘dreamlike’… and increasingly aimed at a young audience.” Schatz identifies “Jaws” (1975) as the progenitor of the New Hollywood blockbuster, but “Psycho” laid the groundwork for the “sensory, dynamic” appeal of post-classical cinema.

From its initial screenings, audience reactions were unprecedented: gasps, screams, shouts, even people running up and down the aisles. Although Hitchcock later claimed he had anticipated this all along, saying he could hear the screams as he designed the bathroom scene, screenwriter Joseph Stefano countered: “He’s lying… We had no idea. We thought people would gasp or be silent as they watched, but scream? Never.”

Contemporary reviews unequivocally acknowledged the unprecedented nature of the audience’s screams: “The film is so well-made… that audiences will do something they almost never do anymore – yell at the characters in the film, hoping to prevent them from walking toward their artfully preordained doom” (Ernest Callenbach, Film Quarterly, Fall 1960).

Controlling the Chaos: A New Moviegoing Etiquette

However, the challenge for Hitchcock and every theater manager was how to prevent these reactions from spiraling out of control. According to Anthony Perkins, audiences often missed his entire sequence of mopping up the floor in the hardware store and dumping Marion’s body in the swamp because they were still reeling from the bathroom murder. According to Stephen Rebello in “Alfred Hitchcock and the Making of Psycho,” Hitchcock even asked Paramount to allow him to remix the film to reflect the audience’s reactions, but was denied.

Hitchcock’s unprecedented “special policy” of barring anyone from entering the theater after the film had started served as both an encouragement and a means of managing the chaos. It ensured that viewers would fully experience the shock of the protagonist’s sudden murder in the shower. More importantly, however, it transformed the casual act of going to the movies into a more ritualistic activity, involving arriving on time and patiently waiting in line for admission.

Hitchcock reportedly conceived the idea of not admitting latecomers during the editing process: “I suddenly insisted, loudly, that all the effort I had put into ‘Psycho’ from start to finish, inside and out, should not be wasted – that everyone in the world must see the film from the beginning to the end and enjoy my work to the fullest, which startled my colleagues. That’s how the film was conceived, and that’s how it must be watched” (Motion Picture Herald, August 6, 1960).

In a narrow sense, this simply meant that Hitchcock, having painstakingly set up the surprise of the bathroom murder, wanted to ensure that audiences would fully appreciate it. But in a broader sense, his demand for punctuality ultimately led to fixed showtimes, tighter screening intervals, the elimination of pre-show cartoons and shorts, and patient queuing – all standard procedures of the contemporary moviegoing experience.

The Ritual of Fear: A New Kind of Audience

Critics lauded Hitchcock’s new policy: “In any other form of entertainment, from ice shows to baseball games, most of the audience arrives before the show begins. Not so with movies, which have operated on the policy of cramming people in whenever they arrive, regardless of how the latecomers might affect the plot.” Columnist Stan Delaplane detailed his experience of going to see “Psycho,” capturing some of the psychological undertones of the new viewing regime.

"There was a long line at the theater – they only let you in before the show starts, no one in the middle… A recording of Mr. Hitchcock was playing on the loudspeakers.

"He said it was absolutely essential – with his pronounced English accent. He said you absolutely must not come in after the show starts.

"Then a few women’s screams came over the loudspeaker, which got the blood boiling. The ticket taker started tearing tickets and letting us in.

"I had read reviews of the film in London months ago. The English critics panned it, saying it was ‘too contrived,’ ‘not up to Hitchcock’s standards.’

"I don’t know what standards they were talking about. But I must say, Hitchcock… didn’t seem the least bit flamboyant. He got us excited.

"Screams all around! We were all slumped in our seats. After wiping the sweat from our palms on our mink coats, we left in an orderly fashion to get hamburgers. Letting the next batch ‘enter and die.’

"Well, if you read the trade papers, you know ‘Psycho’ made a lot of money.

“Which means we’re going to see a series of similar films” (Los Angeles Examiner, December 9, 1960).

Clearly, Delaplane’s audience is docile. Their pleasure is rooted in this docility. However, we can see a performative element at play in this enjoyment of arousing a collective submission to fear and release. In this highly ritualized masochistic submission to a familiar “master,” we see screams and shouts frankly understood as “excitement,” followed by a highly sexualized climax (“enter and die”), a feeling of collapse, and then a restoration of appetite (both literal and metaphorical).

Despite the class (mink coats and hamburgers) and gender of the audience, they have a new awareness of themselves as gathered around certain terrible sexual secrets. The shock of understanding these secrets produces both a discipline and a camaraderie around that discipline, a collective pleasure that was new to cinema and subverted traditional gender roles for the audience.

The Art of the Tease: Marketing Fear

Another important tool in disciplining the “Psycho” audience was the trailer. All three trailers hinted at the film’s secrets, but unlike most “coming attractions,” they didn’t reveal too much. In the most famous of these trailers, Hitchcock serves as a tour guide of the Bates Motel and the house next door (now converted into a Universal Studios theme park, complete with the “Psycho” house and motel) on the Universal Studios lot. Each trailer emphasized the importance of special discipline: either “please don’t give away the ending, it’s the only one we have,” or the necessity of arriving at the theater on time.

But there was another unreleased trailer that was even more important in instilling discipline in the audience. This trailer, titled “How to Treat and Handle ‘Psycho,’” was not strictly a trailer, but a visual “handbook” instructing theater managers on how to screen the film and manage the audience.

The black-and-white short opens with Bernard Herrmann’s violin score over a street scene outside the DeMille Theater in New York – the site of “Psycho’s” premiere. A long line of people waits on the sidewalk for the matinee. An urgent-sounding narrator explains that the man in the tuxedo in the picture is the theater manager, responsible for enforcing the film’s screening policy – a policy that requires him to direct traffic on the sidewalk while awaiting the opening of this “blockbuster.”

The film then explains the key elements of this procedure, beginning with Hitchcock’s own sly and unflappable voice broadcasting: “Lining up is good for you, it makes it easier to find your seat. It will also allow you to better appreciate ‘Psycho.’” The polite exhortation, coupled with the presence of private detective-like guards and a life-size cardboard cutout of Hitchcock in the lobby – sternly pointing at his watch – seems a bit comical today, as we have thoroughly accepted the discipline of punctuality and secrecy.

Part of the film’s pleasure lies in Hitchcock’s playfully assuming a sadistic posture while simultaneously expressing excessive concern for the audience’s experience. He asks the waiting audience to keep the story’s “tiny, terrible secrets” because his primary concern is the audience’s best interests. (According to Rebello, this strategy was successful – when audience members leaving the theater were questioned by those waiting in line, they simply replied that the film had to be seen). He also upholds the democratic nature of this policy, making no exceptions for the Queen of England or the theater manager’s friends.

Interspersed with the occasional scream of a woman (not Janet Leigh – could it be her double?) and Herrmann’s unsettling score, the film brilliantly documents the process of watching a movie, in which going to the movies is both a more painful experience and a more disciplined act.

Hitchcock leveraged his “master of suspense” persona from television to deliver thrills that the small screen couldn’t match, surpassing television. He garnered the rapt attention that symphony orchestras would envy – and these audiences often preferred the amusement park diversions of letting go of all thoughts, rather than the high culture cultivation that emphasized discipline.

The Power of Pleasure: A New Kind of Control

Lawrence Levine provides a compelling account of the disciplining of American audiences in the latter half of the 19th century in his book “Highbrow/Lowbrow.” Levine argues that while American theater audiences in the first half of the century were highly participatory and unruly, arriving late, leaving early, smoking, heckling actors, stomping their feet, and applauding wildly, they were gradually taught by cultural arbiters “to submit to the creator, to become the instruments of their will, the spectators of the artist’s work.”

Of course, Hitchcock advocated “taming” his audience with the “artist’s will,” but this will served to create sensory stimulation and piercing screams, rather than the passivity and silence that Levine describes. Hitchcock’s constraint on the audience was a more subtle exercise of power, a productive rather than repressive power in Michel Foucault’s terms, integrating knowledge and power in the production of pleasure.

In the discipline imposed by Hitchcock, the efficiency and control exhibited outside the theater need to be seen in conjunction with the fear and release patterns unleashed inside the theater. This discipline is no different from the requirements of emerging theme parks, and it is not based on the distinction between highbrow and lowbrow audiences, nor, like later rating systems, on the stratification of audiences of different ages.

Hitchcock played the role of a sadist who wanted a compliant audience to trust him so that he could provide a cunning pleasure, and we see a new deal struck between artist and audience: if you want me to make you scream in a new way, to experience these previously taboo sexual secrets, then patiently line up and prepare to be stimulated.

Gender and Performance: Inside the Theater

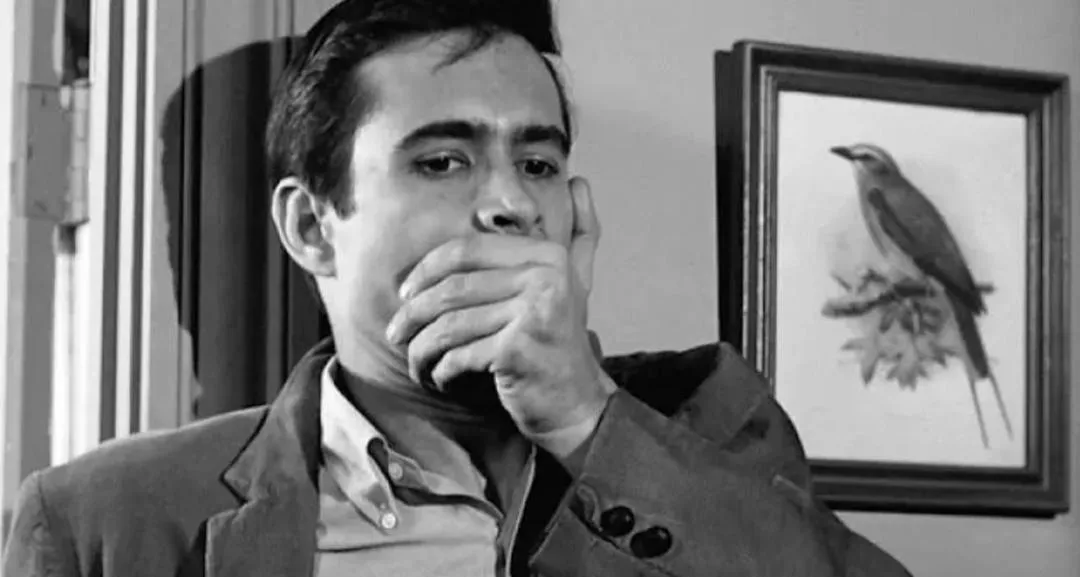

In that film, we see the audience queuing outside the theater for “Psycho,” while photographs taken with infrared cameras during screenings at the London Plaza Theater, and published by the film’s distributor, Paramount, in a promotional brochure, give us a glimpse of what was happening inside the theater. With the exception of a few viewers who looked away, the rest of the audience looked tense, agape, and riveted to the screen. Some defensive postures indicated the audience’s expectations – arms crossed, several people perked up their ears, suggesting the importance of sound in eliciting terror.

Overall, these people were watching intently, some covering their faces or propping their chins with their hands. One man tried to pull out his tie as he clutched it; another bit his fingers, and the young man next to him smoked a cigarette while grabbing his cheek. The people with their heads down in these photos are all women, including one woman sitting next to that cool male smoker who covered her mouth with her hand.

How should we interpret these images of audiences expressing fear? Is it possible that there was a discipline both outside and inside the theater, albeit a different kind of discipline? Of course, we have no way of knowing at what point in the film these images were taken. But we do know that the most terrifying moments in the film occur before and during the appearance of “Mother Bates,” and that these presentations lead to highly feminized fear, first Marion, and then subsequent victims.

The terrified female victim is a cliché of horror movies: the expressions of sexual arousal and fear are both coded as typically feminine elements. As Carol J. Clover puts it in “Men, Women and Chain Saws,” “naked terror” is “feminized.” Thus, the highly sexualized and terrorized female figure is the most traditionally gendered element of the film.

The “Mother Bates” who ostensibly causes this terror is less traditional. “Mother Bates” is clearly female, but equipped with a phallic blade, she represents a new cinematic monster. But Hitchcock’s decision to turn the traditional monster in horror films into a son dressed as his own mother was less about empowering the castrated “monster woman” with violent power than about exploiting the sensational pleasure of sexually ambiguous drag.

The Subversive Power of Gender Bending

The district attorney says, “He’s a transvestite!” He tries to explain the roots of Norman’s behavior, but this explanation is inadequate. Of course, Norman is not simply a transvestite, but someone suffering from a more serious mental disorder, whose entire personality sometimes “becomes his mother,” according to the psychiatrist’s lengthy diatribe. However, in the scene where Norman “becomes” his mother, we see Norman sitting alone without a wig or skirt, reflecting on the sins of “her” son in “Mother Bates’” most feminine voice.

In other words, while on the surface Norman “is” now his mother, the scene visually and aurally varies Norman’s previous sexual ambiguity. The shock of this scene lies in the combination of the young male body and the older female voice: what is fascinating is not one identity being replaced by another, but the tension between masculinity and femininity. This point of view is made even clearer in the penultimate shot, when Norman’s face reveals the corpse of Mrs. Bates grinning.

Therefore, the psychiatrist’s claim that Norman is entirely his mother is unverifiable. Instead, these variations on drag become a satire, even bordering on camp, playing with the audience’s expectations of fixed gender. Norman is not a transvestite, but transvestism is indeed one of the attractions of these scenes.

But if gender play is an important and innovative element in the film, how did audiences view gender play while watching “Psycho”? I believe that gender roles were subverted both on screen and in the theater, and that even the most representative male and female behaviors had a mimetic performative element, subverting gender’s inherent responses.

Thus, although the men in the audience looked masculine, although they appeared calm in the face of the thrills, staring intently at the screen, their postures were somewhat strained. Faced with the source of gender-confused horror on the screen, their steadfast masculinity seemed somewhat contrived. The more they tried to appear masculine – like the man clutching his tie – the more clearly they revealed the threat of femininity.

On the other hand, the cowering, evasive female audience members exhibited the typical posture of frightened women. However, the exaggeration here also suggests a pleasurable and self-aware performance. I once interpreted this typical female response as a rebellion: women refusing to look directly at female victims under the shadow of male monsters, thereby resisting the assault on their gaze.

However, this concept of resistance only assumes the existence of male monsters and the female audience’s dissatisfaction with horror. Now, I am more inclined to believe that if some of the women in the audience refused to watch the screen, they, like my girlfriends and I, were in the early stages of absorbing a certain law that was teaching us how to watch – encouraging us to watch like men in order to experience greater stimulation.

We also need to recognize what those photos cannot show us: that these laws of gender play evolve over time, and although they seem fixed here, they are actually changed by “Psycho.” In the bathroom murder scene, male and female audiences were either stunned or clutched their hands tightly, covering their eyes and ears, and recoiling in fear. For this first sudden attack, they may have made involuntary, very traditional reactions. But by the film’s second attack, these audiences had begun to adapt to this game of expectation, and repeated their reactions in gender-traditional or gender-transgressive ways (but in both cases, increasingly performative).

By the mid-to-late 1970s, “slasher/attack” had become a genre, films like “The Rocky Horror Show” had their own performative lives, and by the 1980s and 1990s, erotic thrillers became a new and active genre, those disciplined performative audiences had given way to the children on the rollercoaster raising their hands and shouting, “Mom, look, no one’s raising their hands!”

“The Rocky Horror Picture Show” (1975)

A Legacy of Thrills and Chills

In “Psycho,” new misalignments emerged between men and women, between normal people and psychopaths, between eroticism and fear, and even between the Hitchcockian suspense we were familiar with and a new, gender-based horror. And it is these qualities that made it a pioneer of the New Hollywood’s various stimulating visual “attractions,” which would become the foundation of the New Hollywood. After making “Psycho,” Hitchcock boasted of his ability to control the audience’s reactions, saying that if you “design it properly in terms of emotional impact, audiences in Japan and India will scream at the same time.”

Those photos of “Psycho” audiences seem to confirm his claim – of course, these photos show his ability to elicit audience reactions – however, we have reason to suspect a certain degree of calculation behind his emotional planning. We have already seen that Hitchcock was actually taken aback by the screams that “Psycho” elicited. Perhaps his carefully designed film screening experience was simply to regain control of an audience reaction that had shocked even him.