Ad Astra: A Journey Inward Disguised as a Space Odyssey

James Gray, the director known for “The Lost City of Z” and “Two Lovers,” presents an existential space drama starring Brad Pitt.

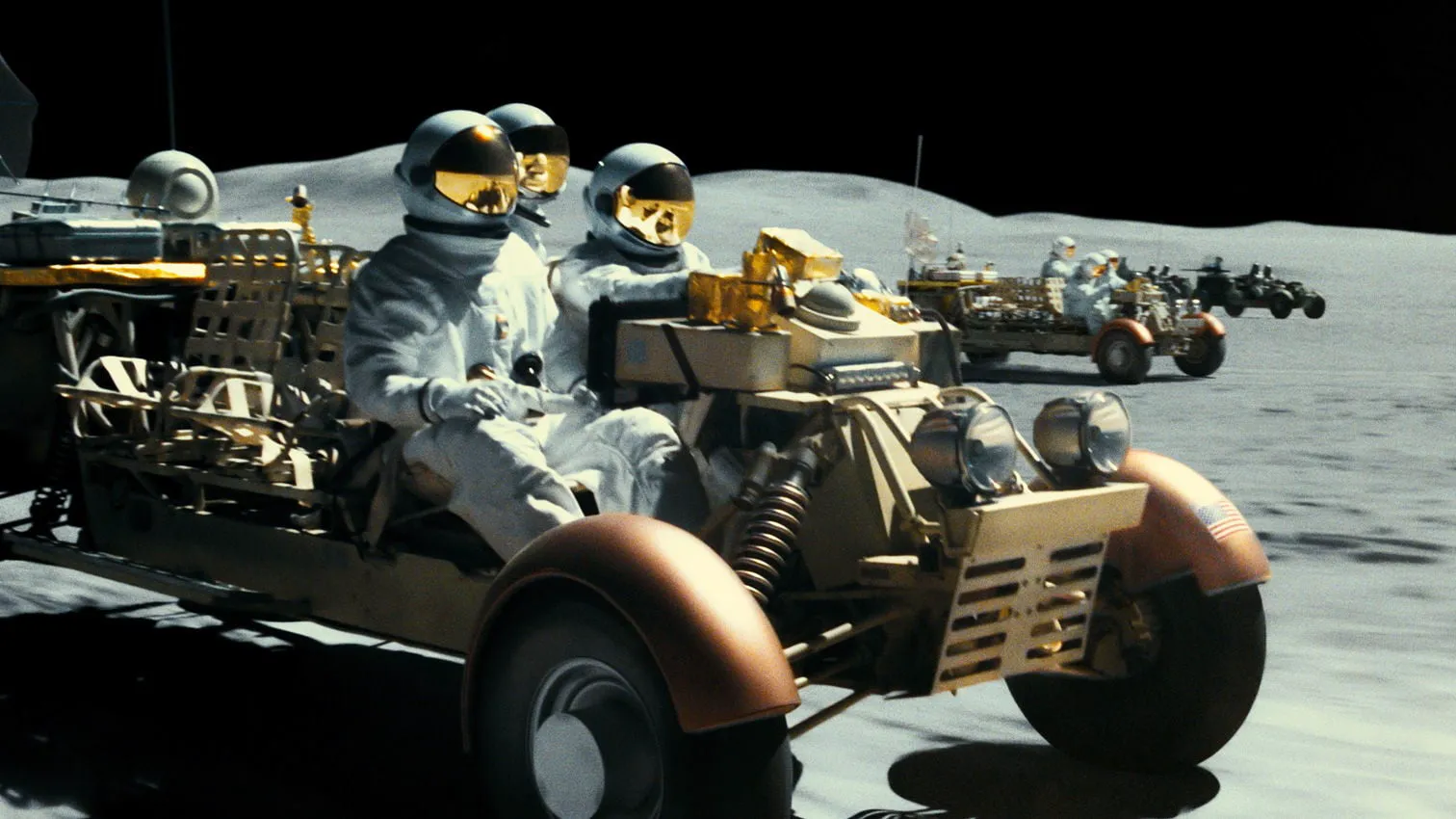

In the near future, humanity has fully embraced space exploration. Lunar vacations are commonplace, and scientists meticulously study the universe from Martian outposts. Roy McBride (Brad Pitt) is the son of Clifford McBride (Tommy Lee Jones), a celebrated astronaut who embarked on a deep-space mission beyond the solar system 20 years prior, only to vanish near Neptune. Roy, now an astronaut himself, is a deeply troubled man. His wife (Liv Tyler) left due to his workaholism, yet he remains fixated on the cosmos, hoping to find answers to his lifelong questions. Meanwhile, Earth faces imminent destruction from powerful cosmic surges originating near Neptune, believed to be linked to Clifford McBride’s lost vessel. Roy is tasked with a critical mission: to contact his father and uncover the truth behind the Neptune anomaly.

The Vacuum of Space, the Vacuum Within

The vast emptiness of space has long served as a metaphor for personal emptiness in art. It provides an ideal setting for introspection, where the absence of external stimuli encourages inward reflection. This theme resonates in films like “Gravity,” “Moon,” and, to some extent, “Interstellar” and “The Signal.” Even Tarkovsky’s “Solaris” critiqued Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey” from this perspective. Recent Hollywood productions, such as “First Man,” “Proxima,” and “Lucy in the Sky,” explore similar themes: astronauts grappling with their return to Earth, yearning for the cosmos while haunted by earthly concerns.

Gray’s Signature Style in Space

“Ad Astra” transcends mere trend-following or political commentary. Gray began writing the script seven years ago, and the film seamlessly integrates into his established filmography. Gray’s protagonists are perpetual outsiders, whom he initially attempts to reconcile with their homes before ultimately sending them far away. This yearning for escape is evident in Joaquin Phoenix’s desire to flee to San Francisco in “Two Lovers,” Marion Cotillard’s pursuit of a better life in “The Immigrant,” and Charlie Hunnam’s relentless search for “The Lost City of Z.” “Ad Astra” shares a close kinship with the latter, both exploring characters driven by an obsessive need to escape, seeking something elusive in the unknown.

Gray masterfully blends profound personal drama with adventurous narratives. “The Lost City of Z” openly references Kipling’s heroic poetry, while “Ad Astra,” stripped of its psychological depth, could be mistaken for a pulp science fiction adaptation. The film’s elements – space pirates, Martian bases, rogue primates, and asteroid field crossings – seem incongruous with a somber exploration of a deeply unhappy man. Yet, this juxtaposition embodies Gray’s unique charm: a modernist sensibility that treats genre tropes with a fresh perspective, unburdened by preconceived notions of “high” or “low” art. In Gray’s hands, “Solaris” can seamlessly morph into “Cowboy Bebop.”

The Pitfalls of Literary Sentimentality

However, Gray’s modernist approach has its drawbacks. “Ad Astra” occasionally veers into literary sentimentality, with monotonous voiceovers reiterating existential questions. Brad Pitt’s narration feels like a late addition, potentially imposed by producers concerned that viewers might miss the character’s inner turmoil. This is unfortunate, as “Ad Astra” excels at nonverbal communication. Pitt’s nuanced performance and Hoyte van Hoytema’s stunning cinematography – reminiscent of Deakins in “Blade Runner 2049” and Lubezki in “Gravity” – convey the character’s alienation and disorientation far more effectively than his monologues. Cinematographically, “Ad Astra” is a remarkable achievement, seamlessly blending the grandeur of a space epic with the intimate warmth of film grain. It’s hard not to wonder how much better the film could have been with less exposition.

Finding Meaning on Earth

Towards the end, the voiceover subsides, allowing Gray’s cinematic poetry to shine. The film culminates in a quiet, understated resolution of the philosophical themes explored in “The Lost City of Z.” “Man must always reach for the stars. Otherwise, what’s the point of having the sky?” a character in Gray’s previous film asserts. “Ad Astra” confidently counters, “There is no point.” Gray suggests that everything one seeks in the cosmos can be found on Earth. Wherever humanity goes, there will be familiar comforts and familiar problems. The film ultimately argues that human connection is what truly matters. While others chase distant galaxies, the protagonist chooses to embrace the beauty of an autumn sunset on the banks of a warm southern river.