Reflections on Cinema: A Personal Journey by Cristi Puiu

As a preliminary note, I must confess that I’ve never considered myself a quintessential cinephile.

My memories of Bucharest’s cinemas in the 1970s are vivid, a time when I was too young to distinguish between theater and film. What truly stands out are the films that profoundly impacted me and the specific theaters where I experienced them.

The first such place was The Romanian Cinematheque. I was about 20 when I saw Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1962) there.

The Exterminating Angel (1962)

A Shift in Perspective

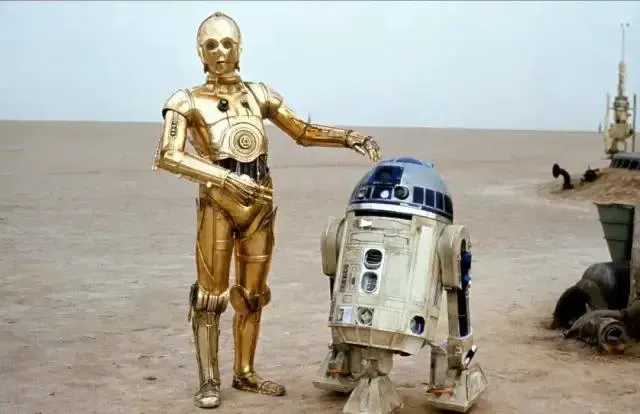

This film revolutionized my perception of cinema. Having always been drawn to painting, I had naively viewed film as a somewhat base art form, akin to watching a football match. I had seen spectacular movies like Star Wars (1977) and The Empire Strikes Back (1980) – the last of such imports for a while. But The Exterminating Angel made me think, “Wow! I never imagined film could be like this.”

Star Wars (1977)

Overcoming Barriers

It wasn’t my own initiative to go; a friend invited me. Coming from a modest background in the suburbs of Bucharest, it was an hour-long journey to the city center. To make that trip for a film, you had to be truly captivated. And many were.

However, I felt a sense of social stratification. There seemed to be a cultural hierarchy, with bourgeois filmgoers at the top. It felt exclusionary. Coming from a working-class family, there was a palpable distance between me and the members of the Cinematheque. It wasn’t just my imagination. You could hear it in their conversations: “You haven’t seen Seven Samurai (1954)? That’s a disgrace! It’s Kurosawa!”

Seven Samurai (1954)

Taking that first step was challenging, but I gradually discovered more films that resonated with me, shifting my perspective. Once inside the cinema, you realize there are no monsters lurking.

Later, at the Cinematheque, I saw Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959) and Nikita Mikhalkov’s An Unfinished Piece for Mechanical Piano (1977). These experiences further transformed my understanding of film.

Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959)

Escapism and the Power of Cinema

The Cinematheque was always packed, especially during the communist era. Some would buy tickets and resell them at inflated prices. There was always a buyer!

It was a form of escapism from the bleakness. In the final years of Ceaușescu’s dictatorship, heating systems were unreliable in winter. You’d watch films bundled in coats, your breath visible in the cold air.

But there were also genuine cinephiles, including young people and students from Bucharest’s art schools. The relationship between film lovers and cinema in 1980s Romania was truly remarkable.

I remember the long lines when the Cinematheque screened Tarkovsky’s Stalker (1979). Seeing Tarkovsky’s latest work was essential. There was a sense of reverence. He was the pope of cinema in 1980s Romania, along with Buñuel, Kurosawa, and several Italian directors – Antonioni, Visconti, Fellini. But not Hitchcock. While I admire Hitchcock, he felt like a god, but still human.

Stalker (1979)

The Changing Landscape of Cinema

Today, Romanian audiences are primarily interested in blockbuster films, much like the rest of the world. The Romanian Cinematheque is nearly empty. I don’t know what happened. The audience vanished, perhaps died.

In the 1990s, many local entrepreneurs opened bars and restaurants.

On the roof of the Bucharest National Theater, there used to be a place called La Motoare, meaning “The Engines,” because of the engines on the roof. An old friend who had worked at the Cinematheque would screen films on a large wall, like an open-air cinema. In the summer, we could watch movies, drink, and chat. It was wonderful, but the place is gone now, due to renovations.

Later, I studied film in Geneva, where there was a cinema called Grütli. Like many Western cinemas, it had a café.

Interestingly, they followed a traditional model, often dividing films into two parts, even if it was a 90-minute movie. The film would pause midway, allowing the audience to chat, have ice cream, smoke, or drink beer for 15 minutes. I loved that.

My film education was lacking when I arrived in Geneva. When I decided to switch to the film department (at the École Supérieure d’Art Visuel), I started watching six films a day. There was a video store called Karloff – named after Boris Karloff – where I would rent and watch six films at a time.

I watched Barry Lyndon (1975) on video and was amazed. Months later, Grütli was showing it, but I was living in Lausanne. I thought I’d miss my train home if I went, but decided to watch at least two and a half hours before leaving early, rather than not go at all. Barry Lyndon was important to me. I have issues with the zoom shots, but it’s still a great film.

Barry Lyndon (1975)

Discoveries and Personal Connections

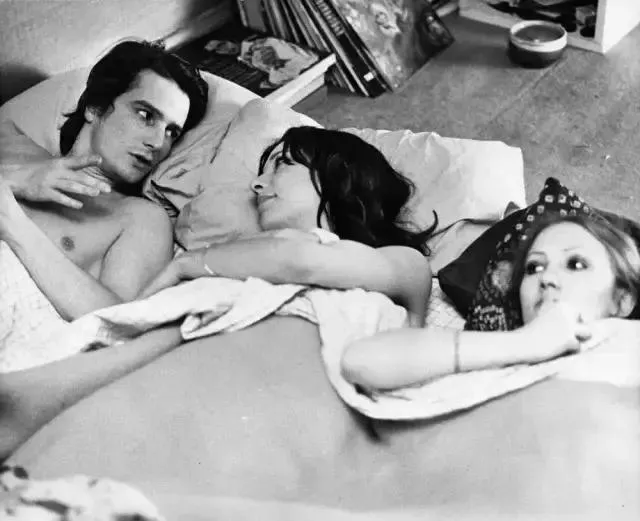

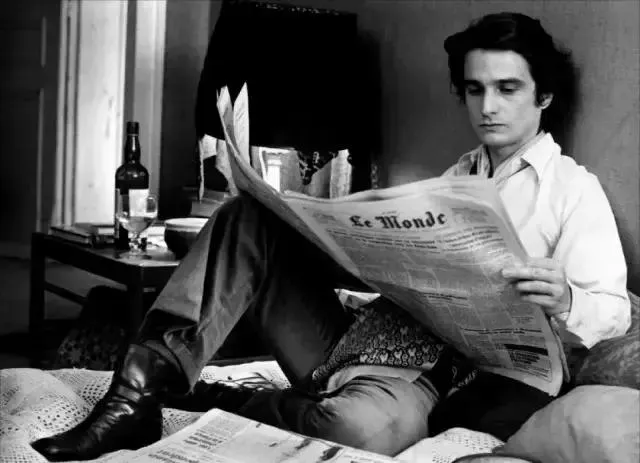

In 2000, I visited my aunt in England – she lived in the Midlands, about 20 minutes from Nottingham – and there was a video rental shop. Having read about Jean Eustache and The Mother and the Whore (1973), I rented the VHS tape. I still have it at home.

The Mother and the Whore (1973)

Shortly after, I made my first film. The French ambassador to Bucharest, Henri Paul, initiated a program where directors could choose a French film to screen at the French Cultural Center. I chose The Mother and the Whore. Seeing it on the big screen was a completely different experience. The cinema was packed, with people standing. It was incredible.

You can’t find The Mother and the Whore on DVD or Blu-ray. Apparently, the director’s family won’t grant authorization, which is sad. So, while cinemas are closing, some films are being withheld for financial reasons. I have the VHS tape, but no VCR, so it’s just a decorative object.

The Essence of Cinema

As I said, I’ve never been obsessed with cinemas, but I love the films I’ve seen in them. If a film is important to me, I’ll see it in a cinema, regardless of the screen size. What matters to me is the experience: the images and sounds.

During the communist era, film imports were restricted for political reasons, but VCRs were booming.

People with relatives abroad could buy VCRs, so in my neighborhood, you could pay 50 Romanian lei to watch five films in a row.

My uncle had a VCR, and we first saw Mad Max (1979) at his house. Films by Jarmusch, Almodóvar, Spike Lee, and Greenaway were unavailable in cinemas. This was how they circulated.

Mad Max (1979)

The Rise of Home Viewing

After the regime change, many cinemas were converted into bars or other establishments. We used to have 450 cinemas; now, including multiplexes, there are only about 100 to 120. Only about 30 traditional (single-screen) cinemas have survived.

I think this is because people became addicted to television and watching films on VCRs in the 1980s. Cinemas became places to watch propaganda films from Korea, China, Russia, the Czech Republic, or Romania. You went there not to see the film, but to spend two hours in the dark with a girl or boy. Like in Cinema Paradiso (1988). For cinema itself, the VCR replaced the cinema.

Cinema Paradiso (1988)

The Future of Cinema

I think there’s a lesson here. Romania now has Netflix, HBO, Mubi, and many other online platforms. You can watch films from around the world at home with coffee, wine, or beer. It’s comfortable, the sound is great, and it’s not noisy. In Bucharest cinemas, people constantly use their phones. I fear cinemas may disappear, perhaps surviving like opera houses, showing old films as special screenings for those who can afford tickets.

After the pandemic outbreak, I was optimistic, but I believe the world will change dramatically.

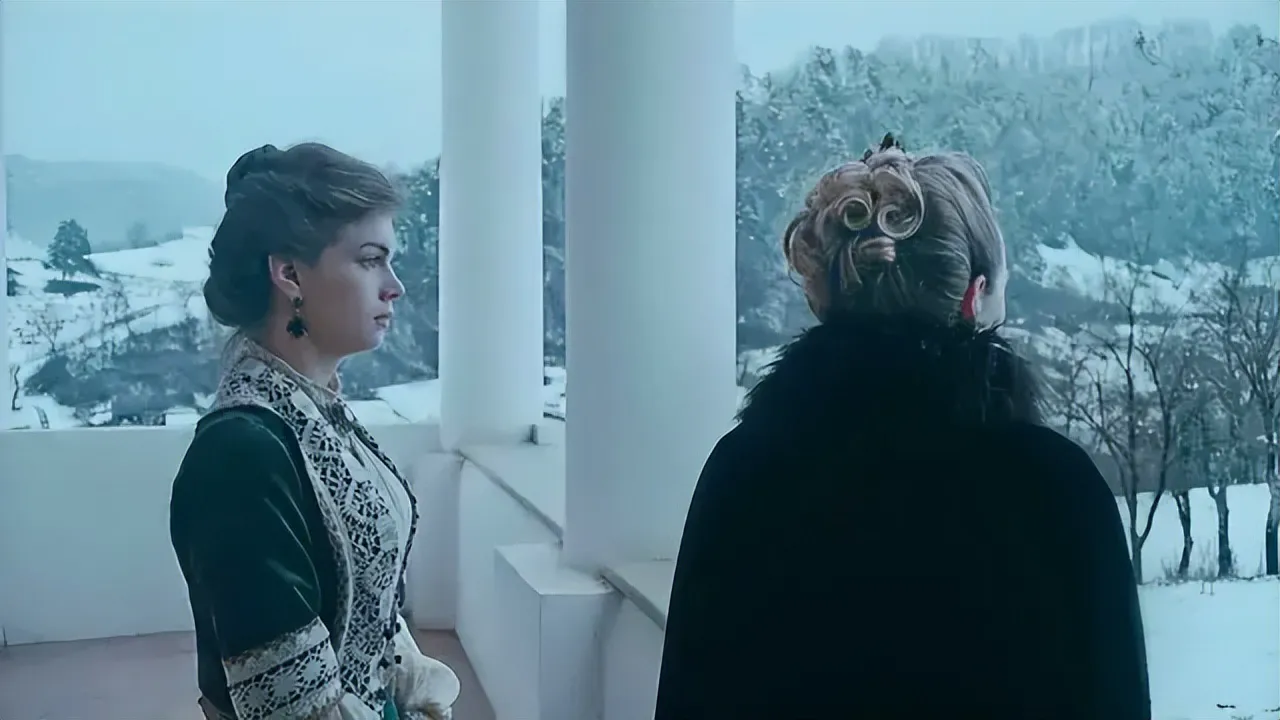

We didn’t release Malmkrog in Romania because the cinemas weren’t open. I told my wife (who is also the film’s producer, Anca Puiu), “Maybe it’s better to release it online.” I didn’t want to, but I didn’t care that much, because there were more serious problems than the release of a film.

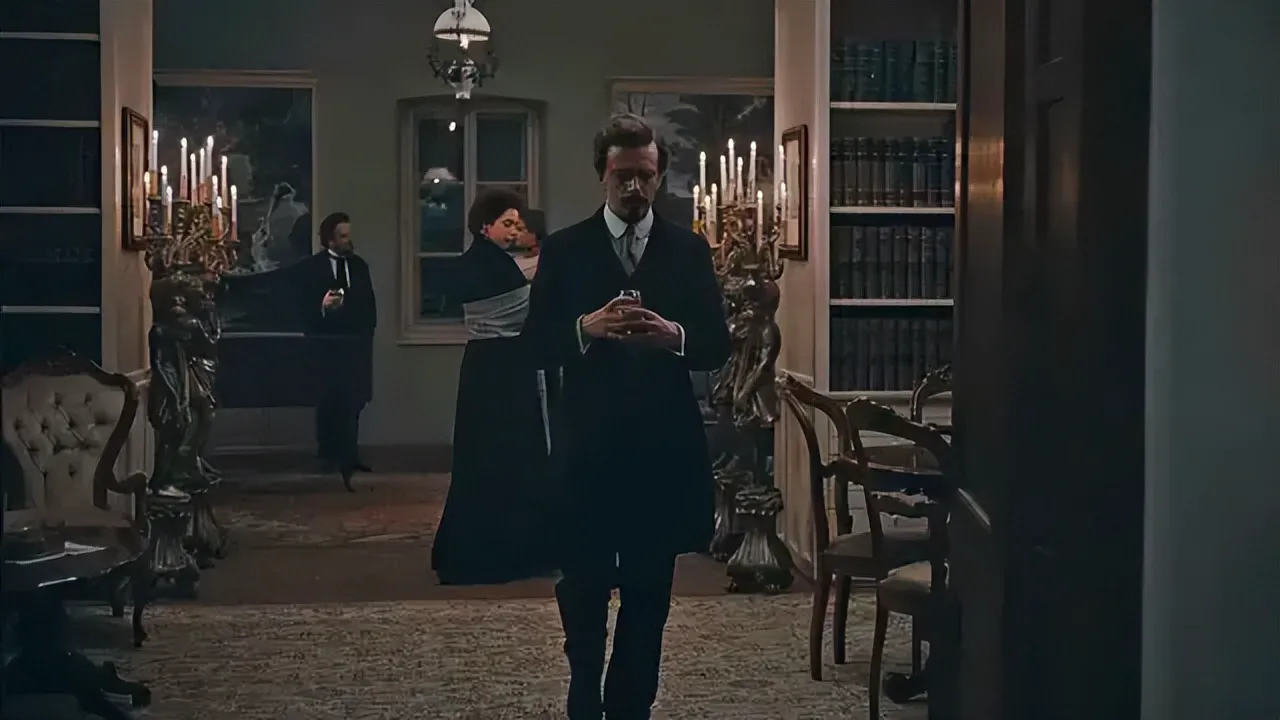

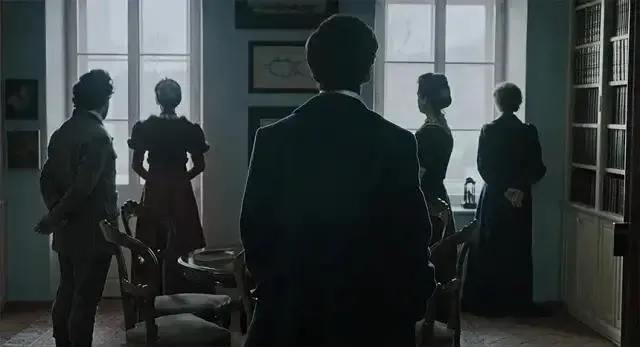

Malmkrog (2020)

My concern is that even when cinemas reopen, people won’t enter them without fear. I think this time is a test for each of us, and for cinemas.

I’m not sure. I’m bad at predictions. Maybe it will take time, and in a year or two, we’ll go to the cinema with friends again. Theaters are older than cinemas, and people still go to theaters. You can still buy vinyl records.

The instinct for adaptation is both our friend and our enemy, especially in the current situation. For example, you can’t imagine something that doesn’t already exist. As Borges said, all magical things are made up of elements that already exist on this planet, otherwise you can’t imagine them. Maybe the dreamers who shape the world with their wisdom, talent, intuition, and inspiration will come up with something to replace cinema. You never know, because cinemas are only about 100 years old. 100 years is nothing.

Malmkrog (2020)

The Importance of Discussion and Community

I started out studying painting. I’m not one of those directors who dreamed of being a director since childhood. I discovered cinema little by little. I love cinema, I love what I’m doing, but I spent my youth reading books, not watching films. So I think what happens after the film is as important as what happens during it. The conversations, discussions, and debates in cafes or bars are crucial.

The question I ask myself is: Will the public places where people meet be closed forever? Will this culture disappear? The markets in cities and towns – the squares, the open-air markets: will all that change? I don’t think so. I think it’s in our DNA.

A film includes the film itself plus the discussion about the film; a book includes the book itself plus the discussion about the book. When I like a book, I buy 10, 20, 50 copies to give to friends so we can discuss it together.

I’m optimistic. I believe it’s hard to break this habit. In every social model, there’s a place where people meet, talk, and exchange ideas, feelings, and emotions. Regardless of the social structure, there will always be such places, with rich and poor. Even the structure of theaters reflects this, with seats for the nobility and seats for the poor.

I think the inertia of this model is too great to change. I don’t like the word “inertia” much since the 2008 financial crisis, but I believe it’s not a luxury: it’s rooted in our most private structure. It’s part of us.