Diving into the Enigmatic World of Italian Giallo Cinema

When one thinks of horror cinema, images of shadowy specters, ancient curses, or monstrous creatures often come to mind. However, the unique and often unsettling realm of Italian Giallo films offers a decidedly different, yet equally chilling, form of psychological dread and visceral suspense.

Far from relying on supernatural entities or haunted houses, Giallo carves its own niche, specializing in a disquieting sense of unease that expertly blends elements of crime, mystery, and horror. This peculiar genre emerged from the vibrant, tumultuous cultural landscape of 1960s Italy. Initially, it was frequently dismissed by critics and audiences alike as mere “trash,” a lowbrow effort designed to titillate with gratuitous gore and shocking nudity. Yet, despite this critical disdain, Giallo not only survived but thrived, growing into a profound and indelible influence on countless films that would follow, shaping the very definition of modern psychological thrillers and slasher films.

The Curious Origin Behind the Name: A “Yellow” Story

The name “Giallo” itself is shrouded in a certain mystique, prompting many to wonder about its origins. Does it, in fact, have anything to do with the color yellow?

Indeed, it does. In Italian, “Giallo” directly translates to “yellow.” The distinctive moniker stems from a hugely popular series of inexpensive crime and mystery novels published by Mondadori, a prominent Italian publishing house, starting in 1929. These paperbacks became instantly recognizable due to their bright, almost lurid, yellow covers. This bold yellow hue rapidly became synonymous with intricate tales of crime, murder, and deductive reasoning. As these “yellow books” gained immense popularity across Italy, other publishers began to emulate their distinctive design. Consequently, “Giallo” transcended its original meaning, evolving into the widely accepted term in Italy for any suspenseful narrative revolving around crime and mystery.

From Literary Pages to Cinematic Screens: The Genre’s Birth

The overwhelming success of these “Giallo” novels naturally caught the keen eye of Italian filmmakers. In the early 1960s, a visionary group of directors recognized the immense cinematic potential inherent in these suspenseful “yellow” stories, swiftly leading to the birth of the Giallo film genre as we know it.

The figure widely acknowledged as the progenitor of the genre is the master of macabre, Mario Bava, with his 1963 film, The Girl Who Knew Too Much (also known as The Evil Eye). While this foundational film might appear somewhat muted or “tame” by a contemporary audience’s standards, it nonetheless meticulously established many of the pivotal core elements that would come to define the distinctive Giallo style: a seemingly innocent woman thrust into escalating peril, a shadowy and mysterious killer whose identity is a puzzle, and a tangled web of intriguing clues and red herrings designed to keep the audience guessing.

Decrypting the Quintessential Giallo Aesthetic

So, what exactly are the defining characteristics that make a film undeniably “Giallo”? The genre rapidly developed a signature aesthetic, marked by distinctive, recurring tropes that are almost guaranteed to appear:

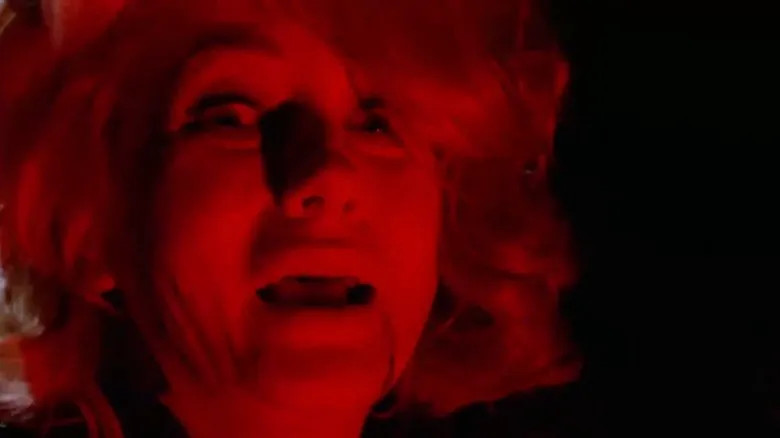

- The Protagonist: A Captivating Woman in Peril Nearly every Giallo film features one or more exceptionally attractive and fashionable women, often portrayed as sexually liberated or highly independent. These alluring figures frequently find themselves at the mercy of unseen forces, becoming the primary victims or targets of the mysterious killer.

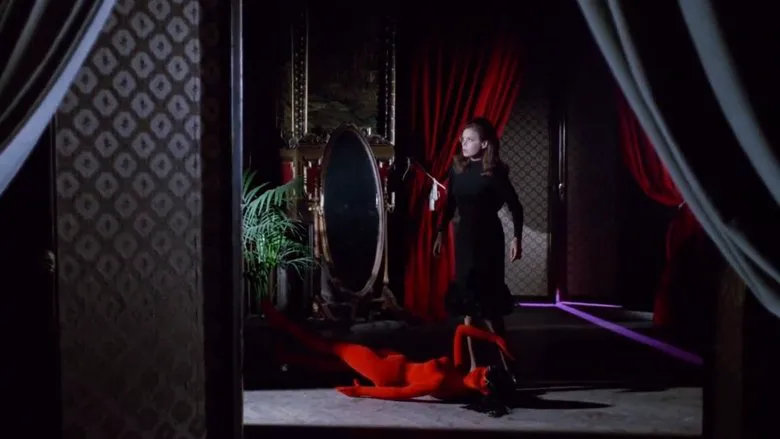

- A World of Opulence and Decadence The narratives typically unfold within lavish, visually striking settings. Picture sprawling, opulent villas, chic urban apartments, luxurious vacation resorts, or fashionable art galleries – environments starkly removed from the mundane reality of ordinary lives. This affluent backdrop often serves to highlight the moral rot lurking beneath the polished surface.

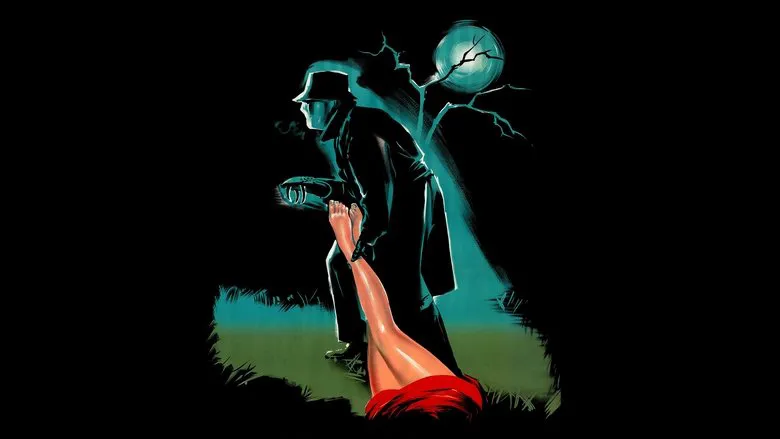

- The Enigmatic, Masked Killer A cornerstone of the Giallo genre is the presence of a gloved killer, their face meticulously obscured by a mask, hat, or cleverly hidden in deep shadow. Their identity and motives remain shrouded in thick mystery, fueling the central “whodunit” aspect of the narrative. This anonymity enhances the killer’s unsettling presence.

- The Knife as the Instrument of Terror Unlike many crime thrillers that might feature firearms, guns are largely absent from Giallo’s arsenal. Instead, the killer favors an array of knives—of all shapes and sizes—wielded with brutal, often ritualistic efficiency. The acts of violence are frequently filmed with stark, graphic detail, emphasizing the raw, visceral impact.

- Intense Erotic Undertones and Stylized Nudity Explicit scenes of intimacy, implied nudity, or full-blown nudity are common. While sometimes perceived as gratuitous and included primarily for shock value or exploitative appeal, these elements often contribute to the genre’s decadent atmosphere and psychological complexity, blurring lines between desire and danger.

The Irresistible Allure of Giallo’s Suspense

Beyond the sensationalized elements and visual flair, the profound appeal of Giallo lies in its relentless, nail-biting suspense. The audience is continuously kept on the edge of their seats, engaged in a desperate game of deduction: Who is the elusive killer hidden beneath the mask? What are their obscure, often convoluted, motives? And, perhaps most pressingly, who will tragically be the next victim to fall? This dynamic mirrors the classic “whodunit” detective stories popularized in British literature. The unyielding tension of watching the protagonist inch ever closer to unlocking the terrifying truth, or desperately evade the killer’s escalating pursuit, creates an undeniably thrilling and immersive cinematic experience.

hol

ogical fragmentation and A Genre-Defining Landmark: Blood and Black Lace

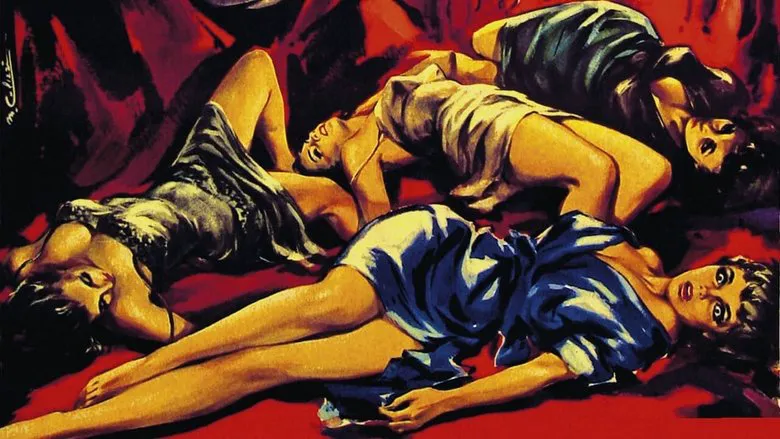

Mario Bava’s 1964 masterpiece, Blood and Black Lace, stands as an absolutely pivotal moment in the evolution of the Giallo genre.

This groundbreaking film pushed boundaries by portraying the killer with an unprecedented level of cold brutality and artistic stylization. More importantly, it solidified and codified the classic Giallo formula: a relentless, enigmatic killer systematically stalking and brutally murdering beautiful victims, one by one, within a fashionable setting. This meticulously crafted template was subsequently adopted by countless films that followed, becoming the de facto blueprint for the genre. Remarkably, Blood and Black Lace predated the explosion of the American slasher film craze by a significant fourteen years, arguably laying a foundational groundwork upon which many iconic horror franchises would eventually build their entire premise.

The resounding success of Blood and Black Lace ignited a frantic race among other Italian directors, spawning a competitive environment where filmmakers vied to create ever more gruesome, shocking, and visually inventive murder sequences. The Giallo genre entered a period of prolific output, with hundreds of similar films being churned out annually. Many of these features were produced quickly and on tight budgets, often recycling formulaic plots with only slight variations to satiate audience demand.

Adapting to Diverse International Tastes

While Italian audiences enthusiastically embraced the Giallo genre in all its visceral glory, international viewers held varying preferences and encountered different censorship standards. American audiences, for instance, often found the films excessively gory, whereas Scandinavian viewers, particularly in Sweden, considered them insufficiently explicit. To cleverly circumvent these international disparities and optimize marketability, directors devised an ingenious solution: creating multiple versions of the same film! Versions destined for American distribution often toned down the explicit sexual content but sometimes amped up the gore, while those intended for European audiences, particularly those in less restrictive markets, included more pronounced explicit content. This practice has, understandably, led to some delightful confusion among Giallo film scholars and dedicated cinephiles, as the same cinematic work may exist under different titles and with surprisingly divergent content across various territories.

The Masked Killer: A Stroke of Genius Born from Necessity

The ubiquitous trope of the masked, gloved killer in Giallo films was not always solely a stylistic choice; it was often a practical necessity driven by the realities of filmmaking on shoestring budgets. Italian films of that era frequently operated with incredibly tight financial constraints, demanding directors to be exceptionally resourceful. By masking or obscuring the killer’s face with a mask, gloves, and dark, concealing clothing, directors brilliantly circumvented the need for expensive, recognizable actors in pivotal but brief roles, and spared the costs associated with elaborate makeup or prosthetics. This ingenious visual shorthand allowed for highly effective and unsettling filmmaking, even on a remarkably tight budget, by allowing various stand-ins to perform the killer’s menacing actions.

The recurring tendency for killers to target women, often in violent and sexually charged ways, was sometimes rationalized within the narrative through backstories of perceived betrayal, psychological trauma, or dark, obsessive desires for revenge. Ultimately, however, it was arguably driven more by the perceived marketability of such dramatic and sensational scenarios in a still-developing cinematic landscape.

Giallo’s Enduring Masterpieces and Notable Contributions

Despite enduring criticism for being exploitative, sensationalistic, or simply “pulp fiction,” the Giallo genre undeniably produced several acknowledged classics that transcend their pulpy origins and are celebrated for their artistic merit. Dario Argento, often hailed as the “Master of Terror,” gave us Deep Red (1975), a film renowned for its meticulously crafted suspense, intricate plot, and the unsettling, almost poetic beauty of its murder sequences. His surreal and visually stunning Suspiria (1977), while blending supernatural elements, remains a masterpiece of atmospheric horror, delivering a uniquely unsettling and opulently eerie sense of pure terror. Other high-quality examples of the genre include Sergio Martino’s giallo thrillers like The Perfume of the Lady in Black (1974), celebrated for its psychological depth and hallucinatory sequences, and Lucio Fulci’s controversial Don’t Torture a Duckling (1972), which delves into superstition, innocence, and brutal violence in a chilling rural setting.

The Waning Years and Transformation of Giallo

By the 1980s, significant societal attitudes had shifted, and audience tastes had evolved considerably. The public gradually grew weary of the increasingly formulaic suspense films that invariably featured serial killers preying upon beautiful, often helpless, women. The Giallo genre itself, in its relentless pursuit of shock value, began to lose its distinctive narrative thread, prioritizing graphic violence and explicit gore over intricate suspenseful storytelling or psychological depth. It slowly but surely morphed into what ultimately became pure slasher films, effectively losing its unique identity. By the dawn of the 1990s, true Giallo films, in their original, distinctive form, had virtually vanished from mainstream production.

The Enduring and Unexpected Legacy

Despite its often controversial nature and the initial critical disdain it faced, the Giallo genre has exerted an undeniably lasting and profound impact on the broader landscape of horror cinema. Its signature tropes—the enigmatic masked killer, the chilling first-person point-of-view shots from the killer’s perspective, the heightened and often exaggerated murder techniques, and the fusion of sex with death—were enthusiastically adopted and adapted by American horror films, particularly during the slasher boom of the late 1970s and 1980s. The enduring influence of Giallo can be overtly seen in iconic franchises such as John Carpenter’s seminal Halloween, Wes Craven’s nightmare-inducing A Nightmare on Elm Street, Tobe Hooper’s brutally visceral The Texas Chain Saw Massacre, and the meta-horror hit Scream.

While Giallo films may have been reductively dismissed as mere “trash” or exploitative cinema in their heyday, they stand today as a significant, eccentric, and indispensable ancestor to the modern horror genre. They masterfully tapped into primal human fears and morbid curiosities with a raw, visceral, and often highly stylized approach, inadvertently paving a colorful and blood-splattered pathway for future generations of filmmakers to explore the darkest corners of the human psyche.