The Frail Boundaries of Faith and Madness in Lee Chang-dong’s Secret Sunshine

Lee Chang-dong’s Secret Sunshine (2007) is more than just a film about suffering and redemption; it’s a poignant drama where the precarious line between madness and faith becomes increasingly blurred.

Secret Sunshine (2007)

The events that befall the protagonist profoundly shape her perception of the world. Shin-ae (Jeon Do-yeon), a young widow from Seoul, relocates with her son, Jun, to Miryang (which translates to “Secret Sunshine”), her late husband’s hometown.

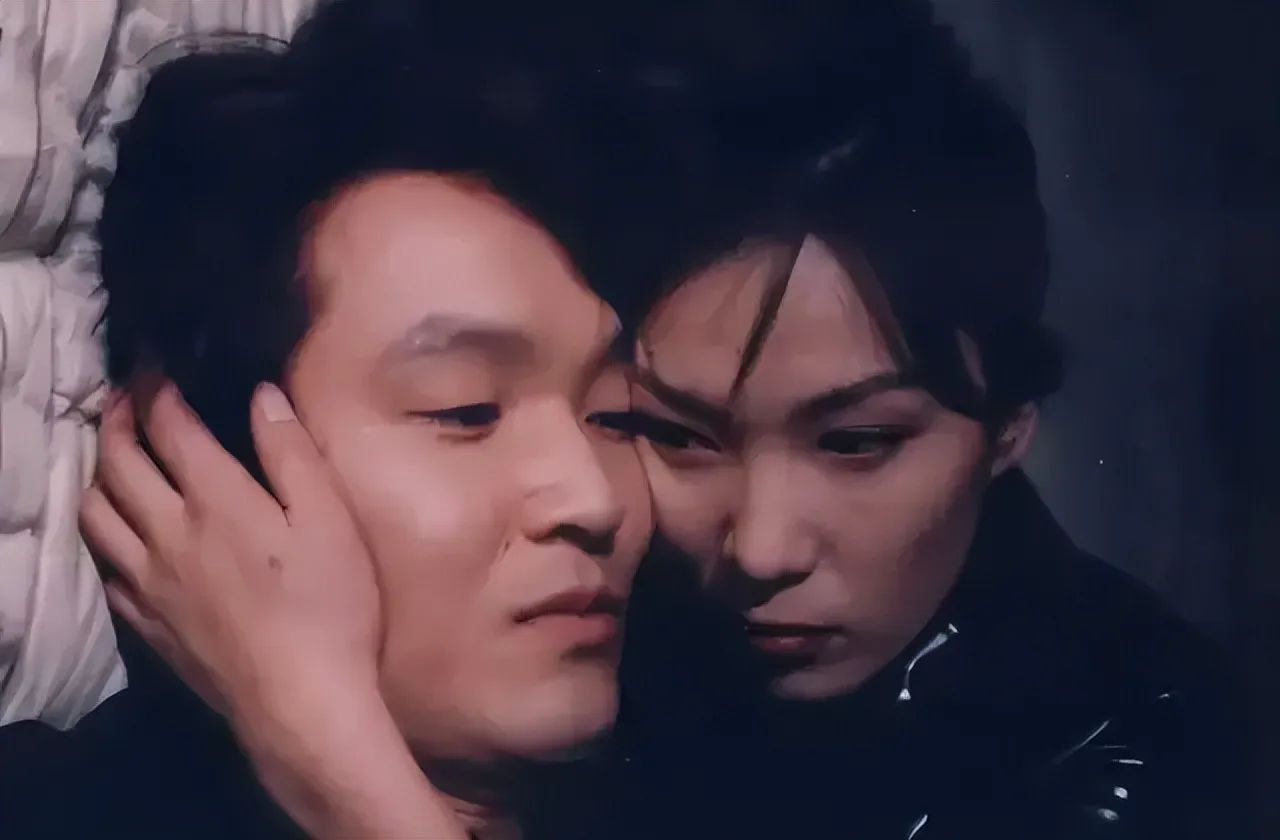

She establishes a piano school, only to find herself the subject of unwanted local attention. Jong-chan (Song Kang-ho), a seemingly affable auto mechanic, assists Shin-ae when her car breaks down upon arrival and becomes her persistent admirer.

The Challenge of Faith

In Miryang, many residents view Shin-ae, the newcomer from the big city, with a critical and disapproving eye. A pharmacist suggests that the love of Jesus Christ is the remedy for all her ailments. Shin-ae, taken aback, attempts to be polite while dismissing her proselytizing.

The pharmacist, looking at her earnestly, calmly suggests that Shin-ae’s distrust stems from a lack of imagination: “Maybe you only believe in what you can see, and you don’t believe in what you can’t see?” This could be Lee Chang-dong’s challenge to himself and his protagonist, a poignant conundrum related to faith and film: it reveals, on the one hand, the need and desire to seek meaning beyond the “visible,” and on the other hand, the slim possibility of finding meaning in life in the absence of faith.

Lee Chang-dong: A Director Exploring the Medium

Secret Sunshine is Lee Chang-dong’s fourth film; since then, he has made a fifth, Poetry (2010). Born in 1954, Lee Chang-dong ventured into film after working as a teacher and novelist for some time (he published two well-received novels in the 80s). Due to this background, critics often consider Lee Chang-dong’s films to have a “novelistic” quality, with the film’s elegant narrative structure and surprisingly multifaceted characters naturally attracting the attention of critics.

But as Lee Chang-dong himself has mentioned, he embarked on the path of filmmaking rather late—he was already in his 40s when he directed his first feature film, Green Fish (1997)—he is a director still exploring the film medium and grappling with fundamental questions about its limitations and possibilities.

Green Fish (1997)

He has said that before starting to film, he always asks himself “What is film for?” Secret Sunshine is a work filled with inner emotions and abstract concepts; it is a study of faith and the power, strangeness, and cruelty it contains; it is a special examination of humanity and experience, all of which are explanations of religious existence and necessity—all of this is to try to depict those “invisible things” in film, the most important visual medium.

Lee Chang-dong has become one of South Korea’s most outstanding film directors on the world stage: he won several awards at the Venice Film Festival with Oasis (2002) and won the Best Screenplay Award at Cannes with Poetry; Secret Sunshine won Jeon Do-yeon the Best Actress Award at Cannes.

But Lee Chang-dong is somewhat different from the other key figures of the “Korean New Wave” of the past 15 years, not only because he briefly served as (2003-2004) the Minister of Culture, Sports and Tourism of South Korea (so far, Lee Chang-dong is the only filmmaker to have held this important position).

Beyond Genre: Lee Chang-dong’s Unique Vision

The most successful and internationally marketable Korean films in recent years have innovated and varied on the basis of genre films, such as Kim Ji-woon’s A Tale of Two Sisters (2003), Park Chan-wook’s Oldboy (2003), and Bong Joon-ho’s The Host (2006). Those who enjoy a reputation in the art film camp are Jang Sun-woo, who directed Bad Movie (1997), and Hong Sang-soo, who directed Woman on the Beach (2006), whose works are more challenging.

Lee Chang-dong’s sensitive and straightforward films do not belong to either camp. His unadorned visual style leads him to downplay his presence in the film, and he is therefore called a humble director. But his films are not nuanced character portraits; they always (sometimes subtly) reveal the greater forces at play in Korean history and society.

Green Fish, which tells the story of a young man from a poor family who falls into crime, is a gangster film set against the backdrop of Asia’s economic miracle in the 1990s. Peppermint Candy (1999) is structured much like Memento and Irreversible, both of which begin at the end of the story and use flashbacks to depict the failures and traumas experienced by the troubled protagonist, with the audience following the film’s perspective all the way back to the Gwangju Massacre. (That year, Lee Chang-dong graduated from Kyungpook National University in Daegu with a degree in Korean literature.)

Peppermint Candy (1999)

Oasis, on the other hand, details the relationship between a mildly mentally disabled ex-convict and a woman with cerebral palsy—the film begins with a terrible, hopeless scene (he rapes her), and tells a Fassbinder-esque forbidden love story that is met with cold eyes and hostility from those around them.

Oasis (2002)

Seeking Normality in Secret Sunshine

The first film Lee Chang-dong made after stepping down as Minister of Culture, Sports and Tourism was Secret Sunshine. In media interviews, he emphasized that he had always wanted to make a “normal film.” He sought to restore a minimalist style, with “ordinary shots” in the film, unlike the magical realism style of Oasis (which occasionally features some exquisite fantasy scenes) or the complex narrative structure of Peppermint Candy.

But more importantly, the “normality” of Secret Sunshine is not only an important, fundamental force, but also a check on the religious themes, a force that allows artists to seek larger themes and mysterious things. When I interviewed Lee Chang-dong in 2007, he likened this approach to an act of purification, saying, “I wanted to remove the mysticism from the film.”

In Poetry, Mija, who suffers from early dementia, is inspired to learn to write poetry. She attends a writing class, and the writing teacher urges his students to observe the environment and things around them more carefully, as if seeing them for the first time. This reflects the clear implicit desire in Lee Chang-dong’s films: to see more and better worlds. The insight of the film is evident in Secret Sunshine, in which the protagonist becomes shaky after experiencing a series of devastating emotional shocks, and is almost in a state of absent-mindedness for most of the time.

Poetry (2010)

The Tragedy Unfolds

About half an hour into Secret Sunshine, the protagonist Shin-ae’s life changes dramatically. Her son, Jun, is kidnapped and held for ransom (Shin-ae has taken a fancy to a plot of land, which is obviously a scam, but it also makes the townspeople think she is rich), and Jun is eventually found dead on the riverbank.

This tragedy clarifies the theme of Secret Sunshine: Shin-ae’s relationship with God (or rather, her relationship with the idea of God), who at first is nothing more than a word in the mouths of others, and after experiencing suffering, Shin-ae decides to believe in God, and finally, she cruelly breaks off her relationship with God.

Lee Chang-dong did something arguably more difficult than making a film without mysticism about the power of faith; he made a film that is skeptical of religious groups, even angry at their hypocrisy and opportunism, but without resorting to mockery and vehement attacks.

Nearly a third of South Koreans are Christian, many of them evangelical; 11 of the world’s 12 largest Christian groups are based in Seoul. It is not difficult for the audience to guess that Secret Sunshine is a work with an “outsider’s perspective”—Lee Chang-dong does not believe in Christianity—the film is not an exposé, but more like a sociological investigation. It is to truly understand that redemptive religion is both attractive and risky, that it can both meet the needs of believers and potentially disrupt their lives.

Shin-ae adheres to some simple doctrines while enduring the temporary, grief-stricken mental derangement, but the warm, comforting Christian community helps her through her darkest moments. In short, Secret Sunshine shows how religion uses us and how we use religion. It is a film about people lying to themselves in order to live. It suggests that there may be no greater lie than religion—but it also acknowledges that timely lies are necessary.

Complex Truths and Emotional Nuances

Lee Chang-dong’s films are full of such complex truths, which are shown to the audience through the accumulation of suggestive details and performances with psychological undertones, rather than simply emotional catharsis. The audience can clearly experience this complex feeling in two key plot points in Secret Sunshine: Shin-ae’s conversion and her disillusionment, two elaborately designed scenes.

After her son’s death, Shin-ae, who is mentally strained by grief, walks into a “prayer meeting for wounded souls” accompanied by Jong-chan. The following passage has a certain documentary tension, and religion looks respectable, but a little vague, and the power of faith is both mysterious and can bewitch believers.

During the church’s full-house singing, Lee Chang-dong chose to shoot a long, fixed shot from the viewpoint of the back row of the church, and when Shin-ae’s crying became clearer and clearer in the hymns, he did not shoot her facial expressions. Only when the priest approached her and placed his hand on her head did he turn the camera to Shin-ae, who was shouting heart-wrenchingly.

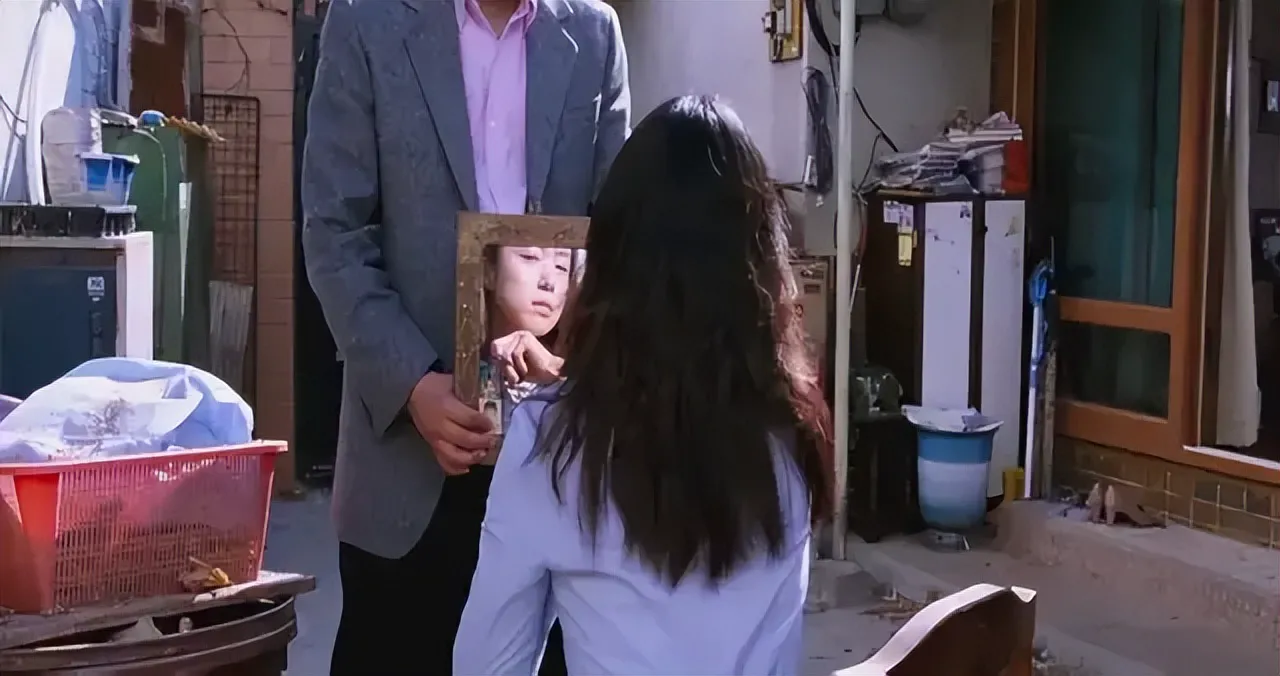

After gradually calming down, Shin-ae convinces herself to accept “God’s will” and decides to visit the man who killed her son in prison in order to forgive her. When she sits across from the murderer (as in the church shouting scene, Jong-chan is also sitting behind Shin-ae), the film tells one of the most pungent, ironic, and morbid jokes. This man, like Shin-ae, has a vacant and stubborn smile after being reborn.

The murderer of her son has also converted to religion and looks radiant. This scene shows that forgiveness and redemption can be so wrong and fragile—at least Shin-ae has learned this. The gradual change in her face reveals doubt and resentment aroused by betrayal. Her inner forgiveness of the murderer suddenly loses its meaning. God has taken the lead and taken away her opportunity to give meaning to life and take control of her life.

A Flawed Protagonist

As written by Lee Chang-dong—Jeon Do-yeon plays this key role in an adventurous, capricious, and completely unpretentious performance—Shin-ae is never the unimpeachable martyr common in “mother melodramas” (nor does she shed elegant tears like a suffering but dignified heroine: she is furious at this unjust world and indifferent God, and she keeps crying, vomiting, and vomiting again).

Shin-ae is clearly prone to making mistakes. She is a loving mother who makes bad parenting decisions, and she may also be a mystery (we can only guess what forced her to start a new life in a place connected to the past, or why she is so estranged from most of her relatives). This sad, hysterical woman ultimately occupies a place in the female portraits of Lee Chang-dong’s works.

It can be said that Lee Chang-dong’s film career began with male-centered works that ruthlessly analyzed the machismo psychology prevalent in Korean films. From Oasis to Poetry, for a director who has consistently criticized machismo and sympathized with women, this can be seen as a reasonable progression, and Lee Chang-dong has created some of the most memorable female characters in recent years.

These women have little to lose; it is because they are (forced to be) somewhat incapacitated—or perhaps more precisely, they become more free—that they can ignore and resist the male-dominated social order.

A Multifaceted Film

As Shin-ae teeters from one emotional extreme to another, Secret Sunshine also never focuses solely on one point—it is a film that contains many elements, including elements of thriller, comedy, and melodrama. Among these elements, Shin-ae finds a long-sought stability in the clumsy Jong-chan.

One of the things that complicates the film’s view of religion is that Jong-chan joined the church in order to get closer to Shin-ae, but he eventually gained his own satisfaction from Christianity. Driven by love, he is a kind-hearted pursuer, whether Shin-ae needs him or not, and he is Shin-ae’s guardian angel in reality.

Lee Chang-dong occasionally fills the wide-screen shots of Secret Sunshine with views of the sky—the opening shot of the film is a bright blue sky seen through a car windshield—Shin-ae has a habit of looking up at the sky, as if looking for some explanation—a reason to keep going. But at the end of the film, the camera focuses on a small, inconspicuous, barren piece of land, and the sun shines on it.

For Lee Chang-dong, a rationalist, it is not surprising to end a spiritual journey in this way. Shin-ae spends most of the film suffering for things that are unseen and unfathomable. At the end of the film, Lee Chang-dong reminds us that the things that can be seen and understood exist on the land beneath our feet, and they unfold from there.