Delving into the Depths of Humanity: A Look at Ang Lee’s “Life of Pi”

As the chill of winter sets in, I find myself drawn to the warmth of home and the captivating world of cinema. When my son presented me with a choice between Korean dramas and the films of Ang Lee, my decision was immediate and resolute: Ang Lee. While his filmography may not be extensive, nearly every piece is a masterpiece, earning him top accolades, including multiple Academy Awards. Films like “Brokeback Mountain” and “Lust, Caution” catapulted Heath Ledger and Tang Wei to international fame, especially the then-unknown Tang Wei. Even years later, the intimate scenes between Tony Leung and Tang Wei in “Lust, Caution” remain a topic of discussion.

This enduring fascination points to a fundamental truth: humanity is the eternal subject of literature. While love is often cited as literature’s most enduring theme, writers and playwrights inevitably confront the complexities of human nature when exploring love. Human nature is inherently fragile, easily tested, and often manifests in animalistic greed and wickedness, leaving little room for ambiguity.

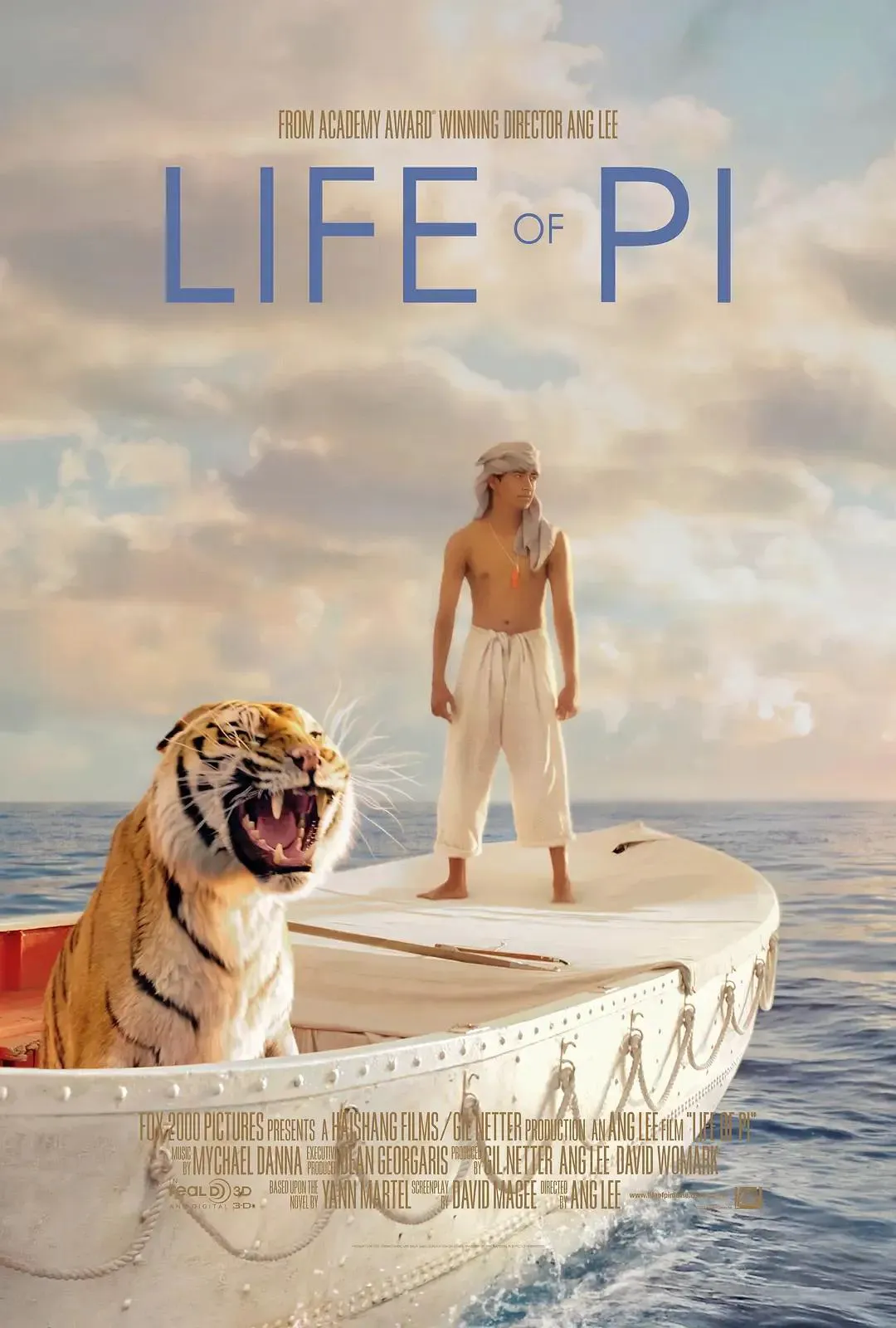

Speaking of human nature, I want to delve into another of Ang Lee’s masterpieces, “Life of Pi,” which earned him the Academy Award for Best Director. With a remarkable豆瓣 score of 9.1, this film has become a timeless classic for audiences worldwide. I’ll save “Lust, Caution” for another time.

The Essence of Faith and Perseverance

Released in December 2012, “Life of Pi” has stood the test of time, solidifying its reputation as a cinematic gem. Watching the protagonist, Pi (Suraj Sharma), evolve from an innocent Indian boy to a resilient survivor after a devastating shipwreck is truly captivating.

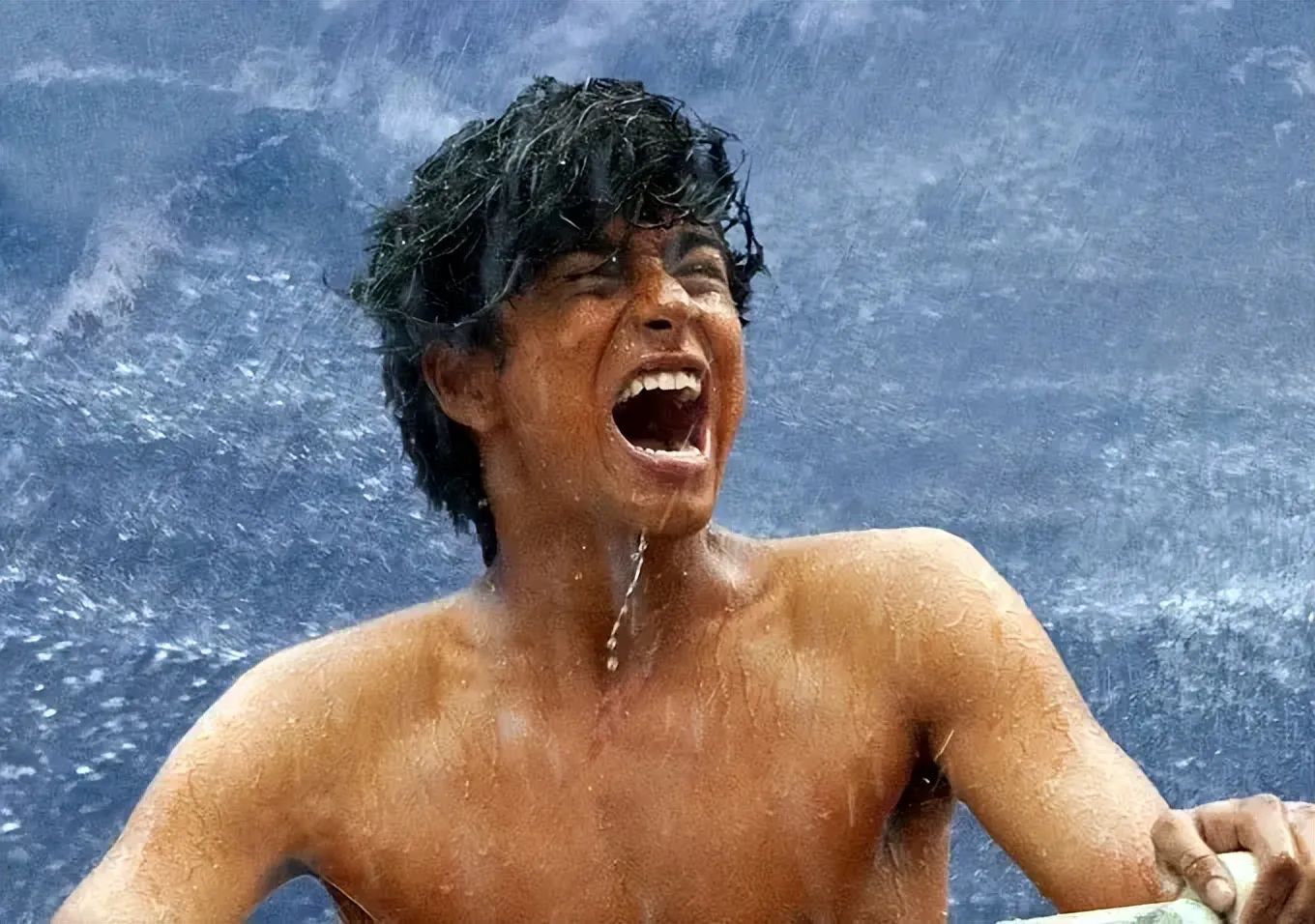

The film depicts a night when Pi is awakened by his brother, who urges him to witness the raging storm on deck. Growing up on land, Pi is awestruck by the sheer power of the ocean. Despite being only slightly older than his brother, he feels compelled to protect his family. He rushes back to the cabin to warn his parents, but a massive wave crashes over him, engulfing the ship and his family. In a desperate attempt to save them, he is swept away, witnessing the tragedy unfold before his eyes.

Amidst the chaos, Pi is thrown onto a lifeboat. He desperately tries to pull his mother to safety, but a burly cook blocks her path, preventing her from reaching the boat. Pi watches in horror as the cook stabs his mother, leaving her lifeless. Later, the cook dismembers her body and consumes it, mirroring the fate of a Chinese sailor. Their supplies had been lost when a pod of whales collided with the ship. Pi is traumatized by these acts of cannibalism.

The Dichotomy of Survival and Mortality

Like Hamlet’s famous soliloquy, Pi faces a stark choice: survival or death.

He realizes that he must save himself. Remembering his father’s words that he can only rely on himself, Pi studies a tattered survival guide. He understands that he must find a way to coexist with the animals on board, especially Richard Parker, a Bengal tiger, who would eventually see him as prey.

The tiger devours a zebra with a broken leg and defeats a hyena, illustrating the harsh realities of the natural world. Pi understands that he must address the tiger’s hunger. He cleverly uses small fish to catch larger fish and even a rat, providing the tiger with sustenance.

He builds a raft and divides the space, allowing the tiger to stay on the boat while he remains on the raft. Gradually, he trains the tiger to respect his boundaries. Pi catches various sea creatures and feeds them to the tiger, who eventually stops seeing him as a food source.

Later, they reach a carnivorous island. Despite the lush greenery and docile meerkats, Pi notices human teeth embedded in the flowers that bloom at night. He realizes that they must leave immediately to avoid the horrors of the island.

These elements contribute to the “fantasy” aspect of the film on a visual level.

However, the “fantasy” in “Life of Pi” extends beyond the visual realm to the story itself. Much of what the audience sees is a product of Pi’s imagination, a fabricated narrative.

The truth is far more brutal.

In reality, there were no animals on the lifeboat, only the cook, a sailor with a broken leg, Pi, and his mother. They were the initial survivors, embarking on a long and arduous journey at sea.

As time passes, food becomes scarce, and the survivors must compete for survival.

This is where human nature is truly tested.

The Ultimate Test of Humanity

The cook is the first to succumb to his baser instincts. After the supplies are lost, he kills the injured sailor and dismembers his body for food.

Pi’s mother, a vegetarian, is horrified by this act and spits at the cook, calling him a beast. In a fit of rage, the cook murders Pi’s mother in front of him and throws her overboard, attracting sharks. This is a scene of unimaginable cruelty.

Pi, unable to bear it any longer, attacks and kills the cook. He then continues to drift at sea, alone with his mother’s body.

However, the lack of food continues to plague Pi. Driven to desperation, he is forced to consume the cook’s flesh.

Having killed and eaten the sailor, and then his mother, Pi is driven to kill and eat the cook in order to survive.

The truth is too harsh, too brutal for Pi to accept.

Therefore, his mind creates an alternate reality. In this version, his mother becomes an orangutan, the cook becomes a hyena, the sailor becomes a zebra, and the tiger represents Pi himself, his primal, animalistic side.

The journey of Pi and the tiger is actually Pi’s own journey, with Pi representing his good side and the tiger representing his savage side.

As for the island, consider why it is populated by meerkats rather than rats. Meerkats are desert creatures, yet they are found in the middle of the ocean. The truth is that the island represents his mother’s corpse, infested with maggots. The meerkats are the maggots. Pi’s departure from the island symbolizes his separation from his mother’s decaying body.

The truth is too terrible to bear, so he chooses to disbelieve it. The insurance investigators in the film also choose to believe the fabricated story.

When Pi tells the first story, he says that the orangutan arrived on a floating banana. The insurance investigators immediately point out that bananas do not float. However, when Pi tells the second story, he does not correct this detail, insisting that his mother arrived on a floating banana.

The inconsistencies in Pi’s story reveal the truth. Eventually, even the insurance investigators can no longer believe him.

Pi likely consumed parts of his mother’s body. On the island, Pi eats the roots of plants, and the tiger eats meerkats, which is a metaphor for eating his mother. The roots represent muscle fibers, and the meerkats represent maggots. In reality, Pi, driven by hunger, ate the maggots on his mother’s body and even some of her decaying flesh.

Because eating his mother is too horrific to contemplate, Pi’s mind creates the tiger to perform the unspeakable act.

Pi says that he left the island because he feared being consumed by it, but he actually feared being consumed by the act of eating his mother, which would drive him mad. He chose to flee the island and forget the truth.

Because he chose to forget, there are multiple versions of his story. When telling the second story to the insurance investigators, he stops after implying that he ate the cook. He is not deliberately hiding the truth, but rather has forgotten it himself. The only remaining memory is the cannibalistic island from the first story.

The conditions for survival at sea are so harsh that there is often no other choice.

Those unfamiliar with the ocean may believe that it is teeming with fish, but most marine life lives near the continental shelf, where the water is rich in nutrients. The deep ocean, like the center of the Pacific, is barren and desolate, unable to sustain life. Pi’s ability to catch fish is not a given, just as it is difficult to find life in the desert.

Despite the hardships he endured, Pi ultimately chooses to embrace goodness, preserve his humanity, and return to a normal life.

“Life of Pi” is a seemingly beautiful film that delves into religion, human nature, and the actions people take in extreme circumstances. It is a film that deserves repeated viewings and contemplation.

Interpreting the Film’s Message

“Life of Pi” tells the story of an Indian boy who survives 227 days at sea with a Bengal tiger named Richard Parker. The novel explores themes of adventure, hope, miracles, survival, and faith. The fantastical journey and the coexistence of innocence and cruelty create a thought-provoking narrative that examines faith, survival, and the relationships between humans and animals, humans and each other, and humans and the world.

The film, adapted from Yann Martel’s novel, has won numerous international awards. Ang Lee’s title, “Life of Pi,” is brilliant. The fact that a defenseless boy and a Bengal tiger can coexist and survive a perilous journey is a testament to the power of faith.

Lee incorporates faith into the emotional fabric of the film. The film’s interpretation of faith is its greatest success. It is not merely visually stunning; it also challenges viewers to confront their own beliefs and consider the existence of God through an unprovable journey.

The film captures Pi’s fear and loneliness during his most difficult moments, as well as his constant cycle of hope and disappointment. This creates a sense of anticipation and suspense, making the film both engaging and thought-provoking.

In the end, when the tiger reaches the shore and disappears into the jungle without looking back, it is a poignant moment of farewell. The lack of a proper goodbye leaves the audience in tears, a testament to the film’s emotional impact.