The Enduring Charm of “Porco Rosso”: A Reflection on Miyazaki’s Anti-War Sentiments

On November 17th, Hayao Miyazaki’s classic animated film “Porco Rosso” was re-released in mainland China. Despite being a film from 1992, it continues to possess a timeless allure.

Porco Rosso Poster

From Manga to Masterpiece: The Genesis of “Porco Rosso”

Between 1984 and 1990, Miyazaki’s manga “Hayao Miyazaki’s” (Miscellaneous Thoughts) was serialized in the model magazine “Model Graphix.” This work, comprising only 13 chapters, primarily delved into military weapons and war stories, featuring descriptions of aircraft, warships, tanks, and more. Its central theme largely revolved around reflections on and condemnations of war, revealing Miyazaki’s anti-war ideology. “Porco Rosso” is adapted from the twelfth chapter of “Hayao Miyazaki’s Miscellaneous Thoughts,” titled “The Age of the Flying Boat.”

“Hayao Miyazaki’s Miscellaneous Thoughts” Collected Edition

A Unique Protagonist and Miyazaki’s Signature Style

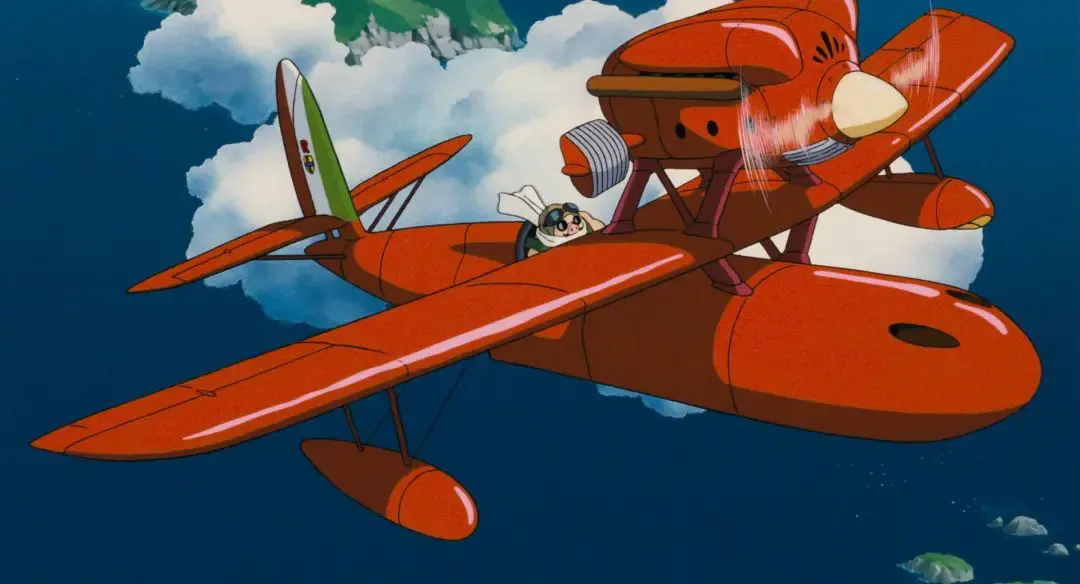

In Miyazaki’s extensive collection of animated works, often featuring young boys and girls as protagonists, the character of “Porco” Marco Rossolini stands out. He’s a middle-aged, overweight pilot, a self-exiled former war hero. The film’s opening minutes showcase Porco’s thrilling battle against air pirates to rescue young girls. This scene perfectly demonstrates Miyazaki’s mastery of depicting aircraft. The red Savoia S.21 gracefully soars through European towns and over the blue sea, seamlessly traversing the sky and land. The combat scenes are not brutal but incredibly romantic, with the elegant and passionate dogfights resembling a dance of airplanes. The kidnapped girls are excessively adorable, showing no fear of the air pirates, eagerly wanting to be taken away, happily adventuring and tumbling in the dangerous air battles, and jumping into the sea one after another to play. Whether it’s the fierce air pirates or the heroic Porco, they are helpless and forced to “surrender” to these lovely girls, which remains a testament to Miyazaki’s gentle touch.

A scene from “Porco Rosso,” featuring the engine with “Ghibli” inscribed on it.

Ghibli: From Aircraft to Animation Studio

Later, during Porco’s aircraft repair, the new engine bears the inscription “Ghibli.” This isn’t a mere product placement by Studio Ghibli. During World War II, the Italian Air Force had a reconnaissance aircraft named “Ghibli,” meaning “wind over the Sahara Desert.” Moreover, the name of Studio Ghibli was reportedly suggested by Miyazaki, befitting his status as an aviation enthusiast. This “aviation enthusiast” indeed has a family background in the field. Miyazaki’s father was an employee of “Miyazaki Aviation,” a family-run aircraft factory that belonged to the military industry. Growing up immersed in this environment, Miyazaki’s understanding of aircraft surpasses that of ordinary people.

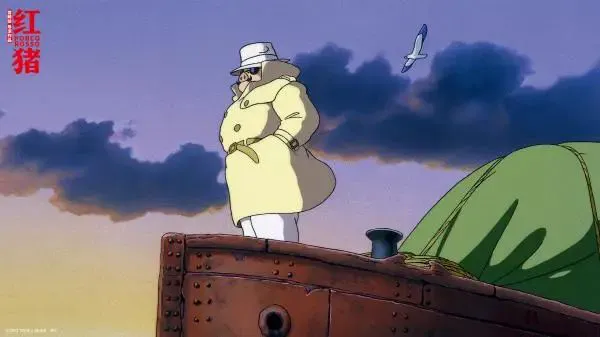

A scene from “Porco Rosso”

Women in Aviation: Reflecting Historical Reality

The appearance of Fio Piccolo, the granddaughter of the mechanic, and her all-female aircraft construction team is an uplifting and stunning segment in “Porco Rosso.” Historically, during World War II, with men widely participating in the war, women filled the significant gaps in the industrial workforce and took on the responsibilities of the family. For example, in the United States, between 1940 and 1945, the proportion of women in the workforce increased from 27% to nearly 37%. In 1943, over 310,000 women worked in the American aircraft industry, accounting for 65% of the total workforce in the industry (before the war, this proportion was only 1%), which corresponds precisely to this scene in “Porco Rosso.”

A scene from “Porco Rosso”

Anti-War Themes and Escapism

Whether it’s the initial rescue of hostages, the aircraft repair, or Porco’s air races, the film’s pace is light and warm. The recurring air pirate alliance seems dangerous but is actually quite endearing. Even when shouting and threatening, they become embarrassed and scratch their heads when scolded by beautiful and brave girls. Even in the flying competition where bullets fly, no one is ever hit. When the bullets run out, they resort to throwing things at each other in the air… The danger never comes from within the people. “What’s the difference between war and earning a bounty?” a young fellow asks. The boss replies, “Those who profit from war are bad people, and those who can’t earn a bounty are just incompetent.” The real villains in “Porco Rosso” are presented as the fascist secret police and the military, which is almost the only cold color in the film and represents the deep-seated pain in Porco’s heart. Italy, still under fascism, is the homeland Porco wants to escape. The past war trauma and the loss of comrades are the past he doesn’t want to face. “I’d rather be a pig than join the fascists” becomes his final stand.

A scene from “Porco Rosso”

Beyond the Surface: A Story of Healing and Mutual Respect

Some viewers might question “Porco Rosso,” viewing it as a story where beautiful young women and mature women fall in love with a pig, a mere middle-aged man’s fantasy. In my opinion, this is a biased view. Naturally, this 1992 work bears the ideological traces of that era, but whether a work serves male consciousness depends on its expressive themes and the portrayal of female characters. The expressive theme of “Porco Rosso” is certainly not male consciousness. Moreover, in works that serve male consciousness, the significance of female characters lies in loving men, competing for men’s attention, and being absolutely protected by men. They don’t need self-worth or self-awareness. In “Porco Rosso,” Fio and Gina have their own life values and self-pursuits. Their beauty exists independently of Porco, their value is not defined by Porco, and their friendship is not defined by Porco.

A scene from “Porco Rosso”

Miyazaki clearly disdains writing a clichéd story of “a prince protecting a princess and living happily ever after,” but rather “a princess saves a monster and then they each find happiness.” This is not a love story but a healing story. Porco, seeing the talented, stunning, brave, and adventurous Fio, exclaims, “Seeing you makes me think there is still hope for humanity.” And Fio sees Porco’s human form and ultimately lifts the curse on him. This is not a mutual pursuit but a mutual appreciation, ultimately pointing to self-redemption. This 1992 work was already attempting to depict a complex emotion that is equal and independent, and it should not be simply and crudely categorized as a “male gaze” perspective.

A scene from “Porco Rosso”

A Hauntingly Beautiful Vision of the Afterlife

In “Porco Rosso,” the most unforgettable scene for me is when Porco tells Fio about his past aerial dogfight. After many comrades and enemies perish together, the exhausted and desperate Porco arrives at the cloud sea plain and has a strange experience: those planes that were shot down like flies rise again and fly higher, converging into a daytime Milky Way in the gray-blue sky. In this solemn, funeral-like Milky Way, the aircraft no longer distinguish between nationality, faction, position, or enemy. The vanished young lives ultimately go to the same heaven. This scene, like the broken Laputa in “Castle in the Sky,” with its lush trees and roots flying alone into the endless void, is chilling. At this point, the film’s anti-war emotional expression reaches a subtle yet firm climax.