The Allure of the “Magic Mountain”: A Pause in Time and the Quest for Meaning

Imagine yourself wrapped snugly in thick woolen blankets, reclining on a balcony lounger. Above, the snow-capped peaks stand eternal, and at night, the sky explodes with a million stars.

Doesn’t that sound idyllic? This is the “horizontal” life in the sanatorium depicted in Thomas Mann’s masterpiece, The Magic Mountain. From the outset, Mann places his protagonist, Hans Castorp, “a perfectly ordinary young man,” in an unusual situation. Hans visits his cousin at a mountaintop pulmonary sanatorium. He follows the sanatorium’s routine, walking, chatting, dining, and resting alongside the patients. However, just as his three-week trip is about to end, he’s diagnosed with a lung ailment and forced to stay, a sojourn that stretches into seven years.

The Magic Mountain

From a worldly perspective, these seven years are a “pause” in his life. Before his arrival, he was poised to join a shipbuilding company as an engineer. This was the natural progression of his unremarkable life: attending school with lukewarm enthusiasm, drifting through university without a clear purpose, and selecting a field of study that was merely less tedious than the others. He was preparing for a life of quiet desperation, yet still respectable. He might have lived out his days in this conventional manner, or perhaps, given his declining but still respectable bourgeois family background, he might have entered politics or become a lawyer.

But this predictable existence is shattered by the sudden onset of illness. He’s thrust into the “Magic Mountain,” a world almost the inverse of reality. In the outside world, modern society adheres to a relentless, linear timeline, but on the “Magic Mountain,” time seems to stand still, and people often forget it exists. In the real world, people pursue honors and recognition, but most on the mountain are shameless, engaging in loud lovemaking in rooms with paper-thin walls, declaring, “I don’t have to do anything anymore; I don’t care about anything.” In the real world, people fear losing their health, but on the mountain, they compete for the severity of their illnesses, with the most afflicted receiving the most respect. Patients with pneumothorax mock those with milder conditions with whistles caused by their ailment. Even the seasons lose their meaning on the mountain; it might snow in August or be sunny.

The “Horizontal” Life and the Stagnation of Time

“Horizontal rest” is the primary activity on the mountain. Patients must recline like this at breakfast, lunch, and dinner. Settembrini, a humanist in the sanatorium who worships reason, civilization, and progress (and is, of course, a patient himself), derides them as “horizontal people.” Indeed, most on the mountain are not only physically weak but also mentally lethargic. The dining table is filled with vulgar jokes and idle gossip—excitement, but not a sign of vitality. They are freed from the burden of honor and the pressure of worldly time, finding a sweet and terrifying comfort in the mountain’s stagnant time.

Is this “horizontal rest” and the “pause” in time a deficiency? At least for much of the time, Hans doesn’t think so. Even when he has the opportunity to descend, he chooses to stay. Or rather, the existence of the “Magic Mountain” itself, as a metaphor for an inverted reality, represents a revelation of the contradictions of reality. Like Hans, many others come and don’t want to leave. This suggests that a tranquil and peaceful secular life may not be so appealing. The mountain is abnormal and vulgar, yet people stay, indicating that the “normal” and “healthy” secular world may be more “abnormal” and “unhealthy” than imagined, merely concealed by mediocrity and habit.

The Malaise of an Era

So, what kind of illness was the era suffering from? The story is set in the early 20th century, a time of turmoil and division. At the same time, Germany had just experienced decades of rapid economic growth. But for the Hanses of the world, this was the glory of their fathers. In his time, the passion for rapid expansion was gone, but the decadent mood of the fin de siècle remained stubbornly. He couldn’t exert himself fully, always drifting along, “not out of fear of hardship, but because he absolutely couldn’t see any necessity for it.” They yearned for passion, but the era they faced fundamentally lacked hope and prospects, leaving them secretly feeling hopeless, without a future, and at a loss.

It was an era that could not pose questions, nor provide answers.

Thomas Mann (June 6, 1875 – August 12, 1955)

In this secular life that was “without a future,” “at a loss,” “hopeless,” and fundamentally lacking “passion” and “meaning,” Hans always felt tired, even when living an ordinary or even privileged life. The “pause” here has a positive meaning because the originally muddled behavior had no meaning, and the abnormality and stagnation on the mountain provided an opportunity for him to fully consider these crucial questions in “horizontal rest.”

More importantly, Hans “was still a blank slate.” His mind was still flexible, and he didn’t have stubborn opinions on those key questions, nor did he stubbornly believe that these questions were unimportant. He had the will and ability to be educated. He was ordinary, but also had the potential to develop. This is why the author both calls him ordinary and “a good man,” and believes that his life has “more than personal” significance. He is “everyone” and can become “anyone.”

A Sanctuary for Self-Reflection

The “Magic Mountain” also provided an environment for him to “cultivate himself.” In a decadent but free environment, surrounded by disease and death, he was able to explore these propositions through personal experience. At the same time, although most people on the mountain were vulgar and lacked any potential, there were still a few who were abstract and profound, able to provide him with intellectual stimulation. In this sense, the seven years on the “Magic Mountain” did have a kind of wandering quality. Hans provided an objective perspective, and readers could follow his various experiences, hear voices from all sides, and enter the puzzle about “meaning” together.

The first answer that jumps out is “eros.” This is a predictable answer. In the Romantic movement, romantic love was long regarded as a value opposed to utilitarian reality and was given sublime meaning. Love can represent breaking through order, representing a rebellion against rational hegemony, and even becoming a proof of self. But this line of thinking always has difficulties, after all, “eros” is so elusive. On his first day on the “Magic Mountain,” Hans was amazed by the undisguised desires of the couple next door. At the dinner table, the sudden sound of “closing the door” led to Hans’s object of infatuation on the mountain, Madame Chauchat. She was a beautiful and rude Russian woman whose appearance reminded Hans of his homosexual friend, Pribislav Hippe, whom he had been in love with as a teenager. His infatuation with Chauchat constituted an important motivation for him to stay on the mountain. Thomas Mann directly indicated the connection between the diseases and eros on the mountain in the book through “psychoanalysis” theory: “The disease is a disguised sexual impulse, and all diseases are nothing more than perverted lust.” Hans’s fever strangely changed with his emotional state. When he received a look of favor from Chauchat, his fever immediately rose, and when he felt hopeless and depressed, or even decided to calm down, his body temperature also dropped. This correspondence is too obvious: on the Magic Mountain, eros itself is a fever.

However, Hans’s infatuation was basically just an abstract fantasy throughout the entire process. It was not until Chauchat was about to leave the mountain for the first time that he had a formal exchange with Chauchat, and his youthful borrowing of a pencil from his admired classmate Hippe was only a one-time opportunity. At that farewell carnival, he almost reproduced the scene of borrowing a pencil from his crush as a teenager to Chauchat. This makes his infatuation with Chauchat on the Magic Mountain after adulthood closer to the satisfaction and reproduction of suppressed desires in his youth, rather than involving real interpersonal connections.

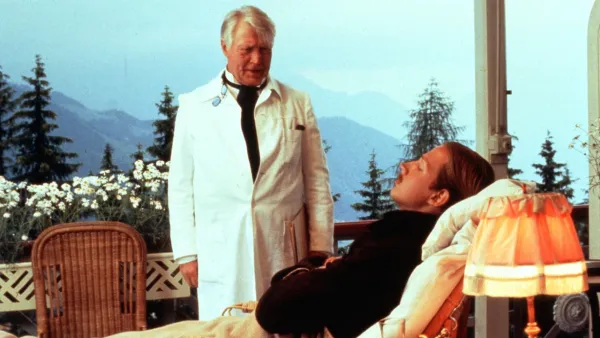

Still from the film The Magic Mountain (1983)

The Clash of Ideologies: Settembrini and Naphta

Secondly, Settembrini and Naphta represent two opposing ideologies. They both strive to become Hans’s educators, vying for his approval, representing different stages of Hans’s intellectual development. Since they often appear in pairs and are constantly debating, it is best to put them together.

Settembrini is an Italian humanist whose grandfather participated in revolutionary struggles. He fervently believes in the power of enlightenment and humanism, which was once the ultimate answer to the question of “meaning” a century ago, but seems outdated in this era. Therefore, although Settembrini has a strong desire to educate others, he always presents a bit of a comical color in his incessant teachings. He advocates the spirit of enlightenment and humanism, praises almost without criticism all the “civilized” achievements brought about by modern capitalism, and optimistically believes that under the guidance of the basic values of enlightenment, human society will continue to progress and a bright future is near. But as Naphta ruthlessly exposes, Settembrini’s biggest problem is that his theory leads to fundamental hypocrisy. He wishfully yearns for a vision of world peace, to the point of misjudging all the implicit crises in the world at that time. He believes in civilization and enlightenment, but ignores the actual existing inequalities (he hardly discusses any issues related to class). His theory ultimately leads to a kind of self-loathing after excessive excitement: when he tries his best to praise the sublimity of the spirit and criticize the diseased and weak body, it is almost difficult for the listener not to notice that he himself is the kind of “patient” he severely criticizes; he tries his best to praise the work ethic and modern civilization, but he himself is the one who has been eliminated by this civilization (he hardly works and is detached from the secular world). Every time he arrives, he always turns on the bright lights in Hans’s room, placing himself in a seemingly perfect light, while Hans only feels ashamed in contrast to this strong light.

Naphta is another picture. He appears in the second half of the story, at which point Hans has actually seen through Settembrini’s disguise through personal experience and learning. Naphta is a Jesuit, and based on his faith, his vision of an ideal world and the answers to all fundamental questions is the “Kingdom of God.” He has a very deep critique of modern society, and on this basis, he always ruthlessly exposes Settembrini’s hypocrisy. He criticizes the commercial logic of capitalist society for destroying ethics and morality, and based on this, his thinking is mixed with some communist critical consciousness (it is said that one of the prototypes of this image is the famous Marxist theorist Lukács). But his path to the “Kingdom of God” is bloody and violent. He advocates war and violence, pursuing a kind of “sacred terror.” From the perspective of his foresight about the upcoming war, he may indeed be more敏锐 and honest than Settembrini. But his worship of violence is difficult to convince people. Hans admits that in the debate between Naphta and Settembrini, the more profound side is often Naphta, but “Settembrini is at least a good person.”

The Contradiction Between Contemplation and Practice

However, whether it is Hans’s infatuation with Chauchat, which has a strong “hallucinatory” nature, or the highly speculative arguments of Settembrini and Naphta, they are too abstract. On the basis of all these questions, there is actually a more essential contradiction. This is the contradiction between the “contemplative” nature of the mountain and the fundamental “practical” nature of human life. No matter how exciting Settembrini and Naphta’s intellectual clashes are, or how exciting the psychedelic eros is, they all have the color of “death” because of their abstraction. This is the fundamental metaphor of the “Magic Mountain,” this is the place of “death.” And no matter how disgusting the world below the mountain is, it is still the ultimate place for people’s activities, the land of “life.”

Therefore, in addition to abstract intellectual wandering, in the sanatorium, the place closest to death, the education that death brings to Hans is also not to be ignored. The experience and reflection on death ultimately leads to “life.” Hans had experienced the deaths of his parents and grandfather early on, but at that time he did not have a real feeling about death. He was always told about the deaths of his relatives, but he had never witnessed them with his own eyes. The first time he witnessed “death” was on the Magic Mountain. Experiencing the death of others will make people truly perceive the “mortality” of people for the first time, which is almost the starting point for all thinking about “meaning.” The advanced perspective technology at that time allowed him to see his body structure with the help of optical power, “seeing the decay and decay of the body in the future in advance,” and seeing “what he should not have seen - his own death and grave,” he also learned a lot of scientific knowledge about life, organisms, chemical molecules, and diseases. He and his cousin Joachim temporarily played the role of “knights” to provide end-of-life care to patients on the mountain; and the death of his cousin Joachim was the biggest stimulus before he finally woke up.

Still from the film The Magic Mountain

Descending the Mountain and Embracing Life

No matter how suitable the Magic Mountain is for contemplation, everything he contemplates is still about the joys and sorrows of the world. The days of “horizontal rest” will eventually come to an end, and how to descend the mountain will be a problem that must be faced. Hans had already realized the necessity of “descending the mountain” in a heavy snow, although this realization was still based on contemplation: he realized that Settembrini and Naphta “are both empty talkers, one is debauched and evil, and the other only blows the little horn of reason… For the sake of good and love, people should not let death dominate and control their thoughts.”

Hans chose “life” and chose “love and good,” which is his final answer to the “meaning” of life. However, the problem here has probably just begun. Because “love and good” are still two abstract concepts, how will he descend the mountain? How will he practice the “love and good” he pursues after descending the mountain? How will he affirm that this “love and good” is sincere rather than hypocritical?

The novel fails to give us an answer. In fact, Hans did not descend the mountain entirely consciously in the end. Although before this, the “horizontal rest” state on the mountain had been difficult to maintain, and everyone was in a state of anxiety, the arrival of World War I changed all the time processes and interrupted everything. Hans, with the awareness of “love and good,” rushed to a battle of “blood and evil.” At the end of the story, Hans rushes to the war, and his life and death are unknown.

Hans’s story is over. He pursued “love and good,” but in the end, it was a war that was not “just” that drove him down the mountain and rushed to “death.” This seems to be the most pessimistic side of this story, but it is also honest enough. It nakedly presents the profound reality. No matter how long the individual’s contemplation of the “meaning” problem has gone through, the problem itself cannot escape the construction of the era. My recently favorite movie The Wandering Earth ultimately lands on a touching theme: everyone is a mystery of existence, and also the answer to this mystery. But what it failed to further point out is what the ending of The Magic Mountain reveals to us: everyone is a mystery of existence, and also the answer to this mystery, but the era is the questioner of the mystery. It stipulates the structure of the mystery and also stipulates all possible endings of the mystery. Within this structure, there is endless exploration of going up and down the mountain, and there is freedom and its burden.