A Comet, a Crisis, and a Whole Lot of Satire: A Review of “Don’t Look Up”

In Adam McKay’s “Don’t Look Up,” Ph.D. candidate Kate Dibiasky (Jennifer Lawrence) discovers a previously unknown celestial object while working on her doctorate. Overjoyed, she calls her colleagues to the lab, but Dr. Randall Mindy’s (Leonardo DiCaprio) calculations quickly wipe the smiles off their faces. It turns out that a massive comet is hurtling directly towards Earth, and if nothing is done, there’s a 99.7% chance it will wipe out all life on the planet. With the support of NASA, the scientists head to meet the President (Meryl Streep), but she’s more interested in dealing with political scandals than a global threat. The news is simply ignored by the public, and when the government finally takes action, its ideas are, to put it mildly, idiotic. It seems humanity is doomed.

Leonardo DiCaprio as Dr. Randall Mindy in a still from “Don’t Look Up”

McKay’s Signature Style Meets Apocalyptic Satire

In recent years, Adam McKay has been making films with a very specific method: taking an important but complex topic for the average viewer – like the financial crisis (“The Big Short”) or the workings of the White House (“Vice”) – and explaining it in simple terms, with humorous infographics and other postmodern quirks, something usually reserved for long, tedious documentaries. In “Don’t Look Up,” he seems to adhere to the same style externally: quasi-documentary handheld camerawork, biting dialogues, sudden stock footage, and pop-up captions that break the film’s fabric and shift the conversation into reality. But only the events are now fictional, a kind of fantasy on a theme understandable to absolutely any layman: a scathing satire on the pandemic reality, in which the government ignores obvious threats, and people look for conspiracy theories where everything is actually transparent.

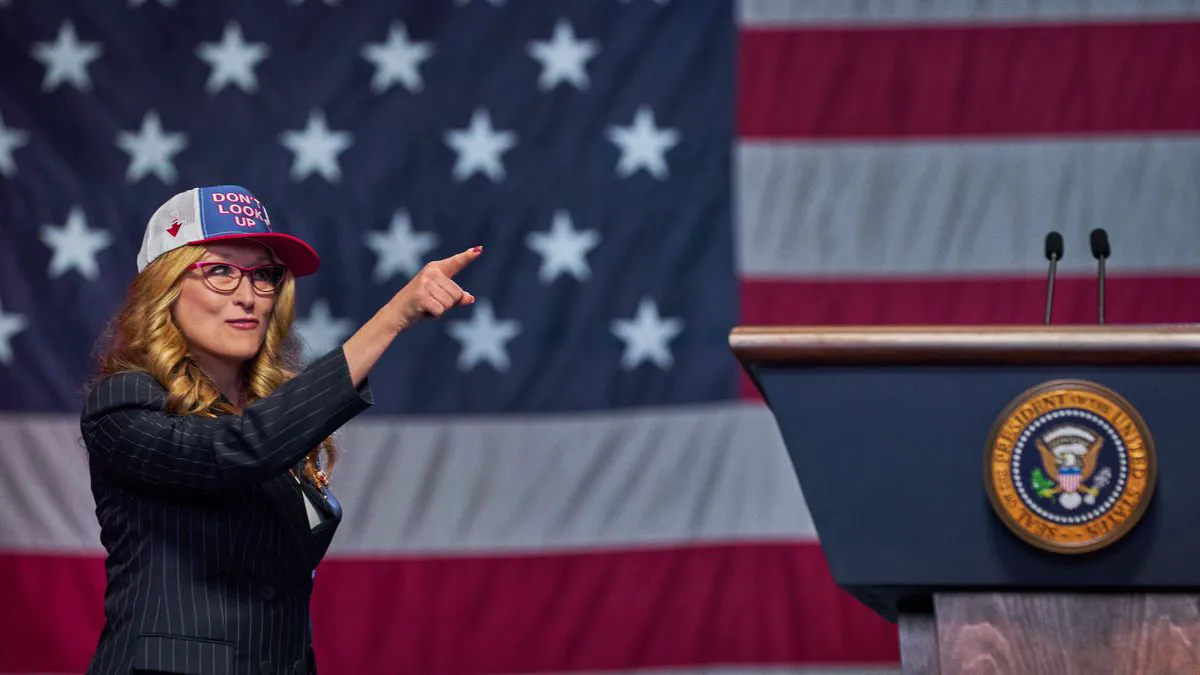

Meryl Streep as the President of the United States in a still from “Don’t Look Up”

When Satire Loses Its Edge

And such a change of context while maintaining style does not benefit McKay. If before all his dramaturgical swagger was justified by the heaviness of the material, now it looks somewhat foreign: as if they are trying too hard to explain something that you knew even before the start of the picture. Yes, the government won’t lift a finger until it’s backed into a corner. Yes, mainstream media tries to make any news “comfortable” and doesn’t want to scare people, even when it’s absolutely necessary. Pop stars are empty shells, the military are pompous idiots, multi-billionaires like Musk are not saviors of humanity at all, but sociopaths with delusions of grandeur. Conservatives and liberals can only argue on the Internet and make memes, they are not capable of anything else. With the latter, by the way, the film has a big problem: “Don’t Look Up” in one episode demonstrates how the actions of the characters affect the World Wide Web, and it is clear that McKay does not understand the culture of the Internet at all. Trying to show the memeification of events, he becomes like a distant relative from “Odnoklassniki,” in 2021 forwarding demotivators to everyone in WhatsApp.

A Barrage of Truisms and a Surprising Dose of Sincerity

Throughout two hours, “Don’t Look Up” throws truisms at the viewer, building a hyperbolized portrait of a post-COVID (or pre-meteorite) society, where all familiar attributes are turned up to the maximum. Sometimes it’s funny, almost always terribly ridiculous – but very rarely witty. But here’s the focus: it seems that this time McKay is not even trying to take wit. His main weapon now is an engaging, sincere anger at everyone he so persistently ridicules. Politicians, businessmen, ordinary people, even liberal Hollywood, just looking for an excuse to create a new blockbuster on a topical theme (that is, he laughs at himself too, fully aware of the opportunistic essence of his film). McKay shows humanity that shouldn’t survive – and you as a viewer are surprised to find yourself rooting for the comet too. In this sense, the film is even closer not to “Vice” with “The Big Short,” but to some “Falling Down,” another armor-piercing and deeply embittered satire, which does not set itself the goal of being at least somewhat subtle.

Cate Blanchett in a still from “Don’t Look Up”

A Reflection of Our World

“Don’t Look Up” by its very existence says a lot about our world. Because how much did it take to bring an author like Adam McKay – a man clearly not stupid and sensitive to what is happening around him – to abandon all formalities and make a film so straightforward in its message? As if he was just tired of explaining something and realized his own powerlessness before the viewer, and therefore decided to just kill humanity to hell, in the end in bright colors showing all its hopeless stupidity. However, you can’t call him a complete misanthrope. When “Don’t Look Up” finishes mocking everyone it can, the film suddenly opens up from a completely new side – as a tender melodrama about people trying to preserve the remnants of humanity in this crazy cruel world. Only by the finale do we understand why the director needed big artists like DiCaprio and Lawrence at all, and not comedians from SNL. Here are these small final scenes, where caustic irony fades into the background, hiding behind the story of small doomed people, who at the family table in the last seconds of life finally understand why they existed at all.

The uneven intonation of the film well mirrors the mood of the characters – running around in circles throughout the film and desperately trying to prove something to someone, then falling into painful apathy, then losing their way due to the popularity that has fallen on them, they eventually come to terms with the world and themselves. The lyrical, almost religious finale stands out strongly from everything that was in the picture before, and at the same time feels the only right one. Both for this particular film, and, apparently, for humanity in general.