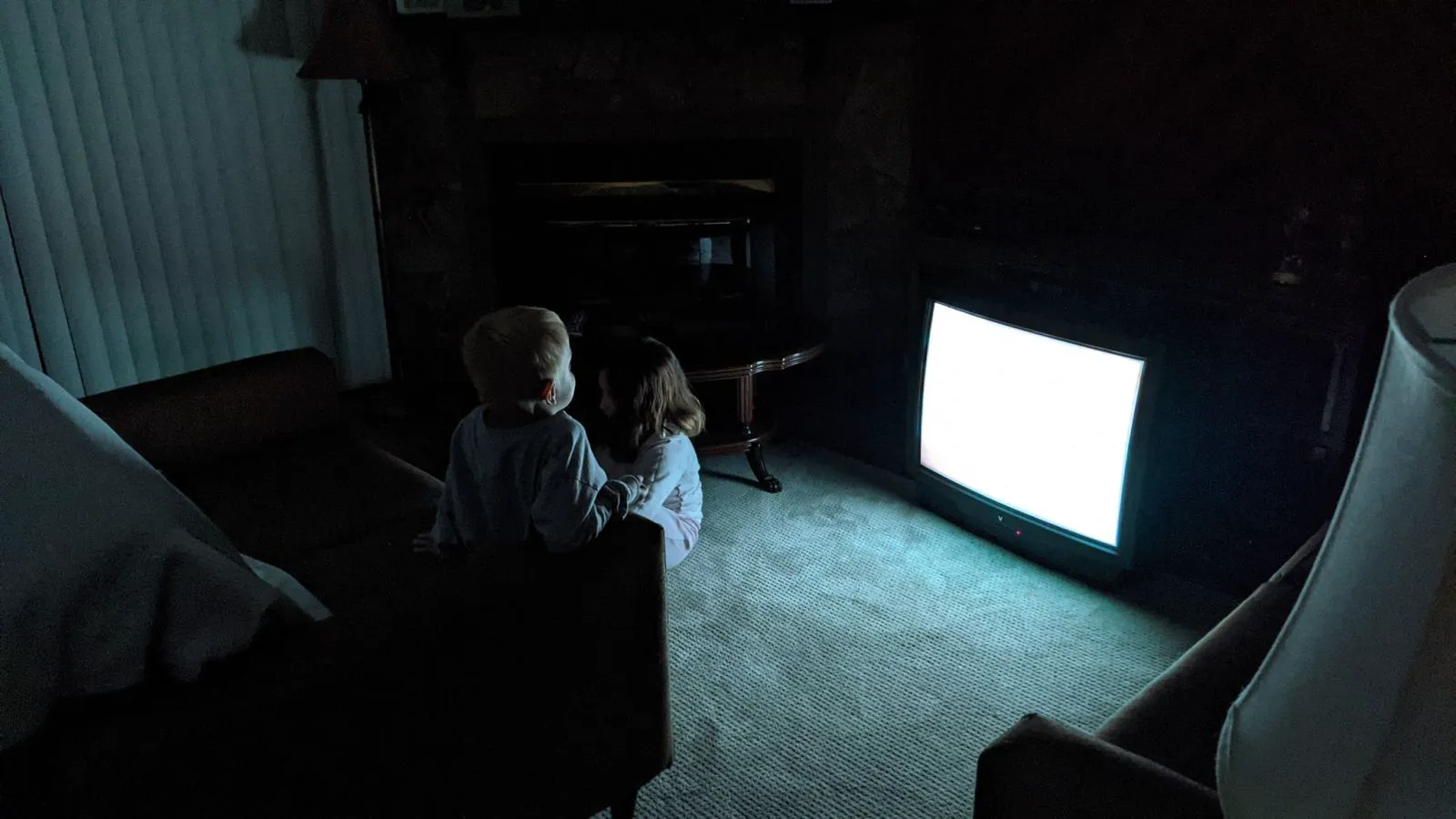

Two young children, Lucas Paul and Dali Rose Tetro, awaken in the dead of night. Their calls for their parents go unanswered, prompting them to venture downstairs to watch cartoons on TV in the living room. The brightly lit room becomes their only sanctuary, for a monster lurks in the darkness, having taken their mother and removed all the windows and doors from the house.

Lucas Paul as Kevin in a still from “Skinamarink”

It’s fascinating to observe how word-of-mouth can differ for various horror films. For instance, Zach Cregger’s “Barbarian” became a hit because viewers urged their friends and acquaintances to watch it with as little prior knowledge as possible—avoiding synopses and trailers. This approach allowed the seemingly predictable film to reveal itself as a bold, suspenseful, and cliché-subverting entry in the genre, packed with WTF moments. The situation is quite different with Kyle Edward Ball’s deliberately paced “Skinamarink.” Without a significant amount of preliminary information, the film might simply enrage viewers.

Still from “Skinamarink”

Understanding Skinamarink

First and foremost, it’s essential to know that this is a low-budget (a mere $15,000) indie horror film that the director shot in his parents’ home. Secondly, the script is based on comments from YouTube users who were asked to share their nightmares. A recurring theme was waking up at night and trying to find parents in the house. Thirdly, “Skinamarink” is an experimental film inspired by the works of avant-garde directors, unfamiliar even to many cinephiles, such as Maya Deren, Mike Snow, and Stan Brakhage. This combination of factors yields an unexpected result: a meditative and narratively ambiguous film that isn’t exactly viewer-friendly. Ironically, the film gained popularity thanks to TikTok bloggers—a platform that some believe exacerbates attention deficit disorder and increases hyperactivity.

Still from “Skinamarink”

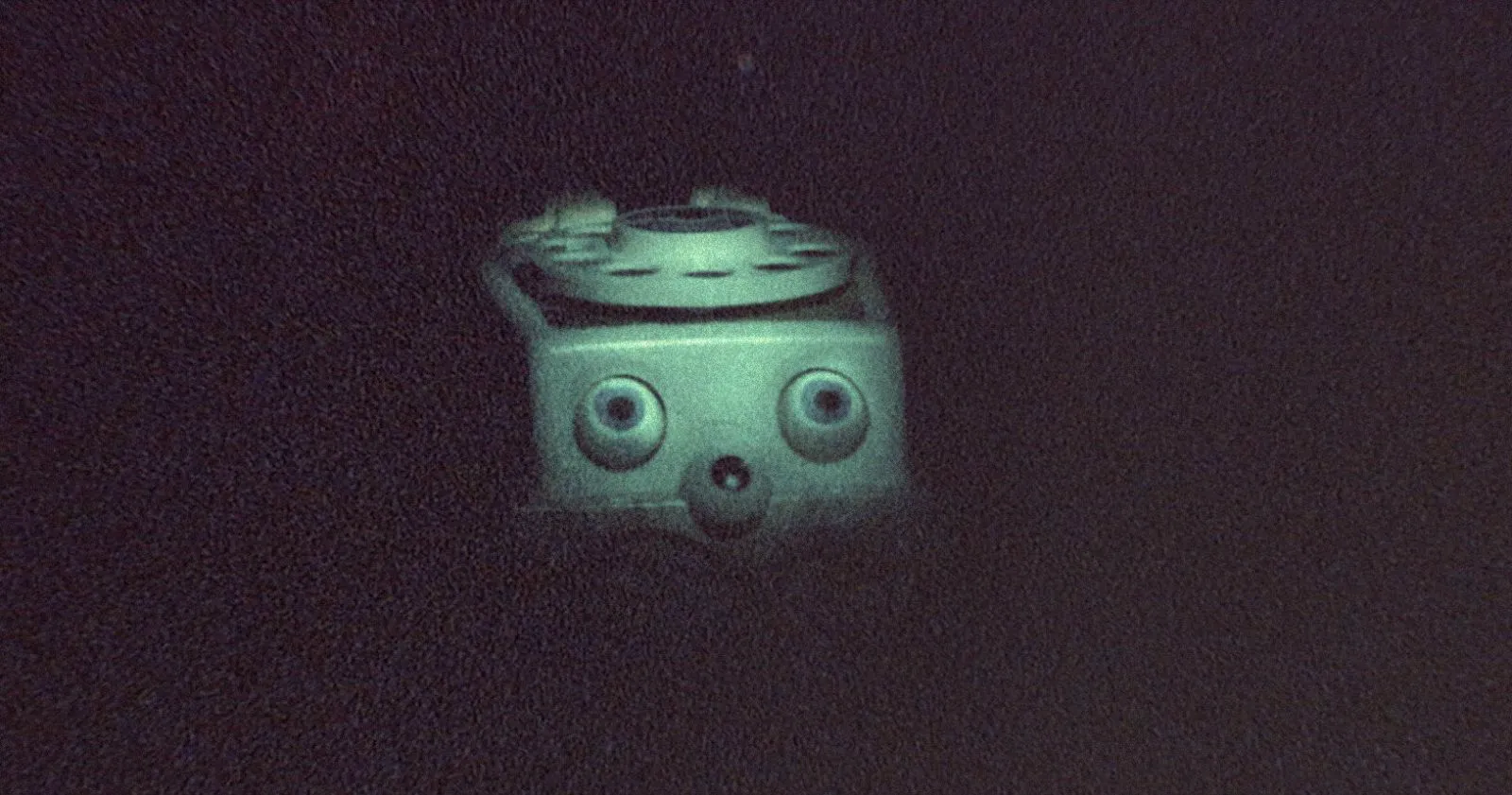

The Unsettling Atmosphere

“Skinamarink” isn’t so much frightening as it is unsettling, built upon disorienting shots and unusual angles: walls illuminated by nightlights, toys scattered on the floor, a bright TV playing cartoons, the backs of adults, the legs of children, and flickering shadows. Kyle Edward Ball constructs the film from what usually serves as filler in most horror movies—short scenes that follow episodes where the plot typically develops and the characters discuss events. The difference is that “Skinamarink” lacks traditional storytelling. Select dialogues are highlighted with subtitles on the screen, but the viewers, for example, never see faces. The entire runtime consists of expressionistic shots of ceilings and walls, the sound of creaking floors, children’s whispers, and the occasional interjection of an unknown voice. The spectacle is immersive and claustrophobic, and most importantly, it preys on old memories of waking up at night in front of a turned-on TV, afraid to make it back to bed. Apparently, this is a universal childhood fear.

Still from “Skinamarink”

Is it Worth Watching?

On the other hand, this exercise in creating unconventional and experimental horror through light, shadow, and a few rooms will likely tire out most viewers. For a film lasting 100 minutes, Edward Ball’s imagination falls short. The set pieces, while effective, become repetitive and monotonous. During the viewing, one inevitably thinks of “The Blair Witch Project” and notices that the film grain effect is fake and looped, with scratches and grain appearing in the same places every few seconds.

Final Thoughts

And yet, “Skinamarink” deserves attention. At the very least, to confirm that indie horror films can still be inventive and bold. Or, for example, to test your own patience and try to decipher a not-so-accessible film. Perhaps it’s all the visions of a dying child who hit their head in the opening minutes, or a metaphor for domestic abuse, with the father as the monster. Or maybe there’s no mystery at all—it’s simply an adaptation of childhood subconscious fears. Either way, “Skinamarink” makes you want to think, reflect on individual scenes, and argue over interpretations. It’s worth admitting that few films today elicit such a reaction. Isn’t that a sign of success?