Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind: A Retrospective

A sci-fi, fantasy, and ecological epic, this anime blockbuster impresses with its grand vision, yet is slightly let down by a heroine who is almost too perfect.

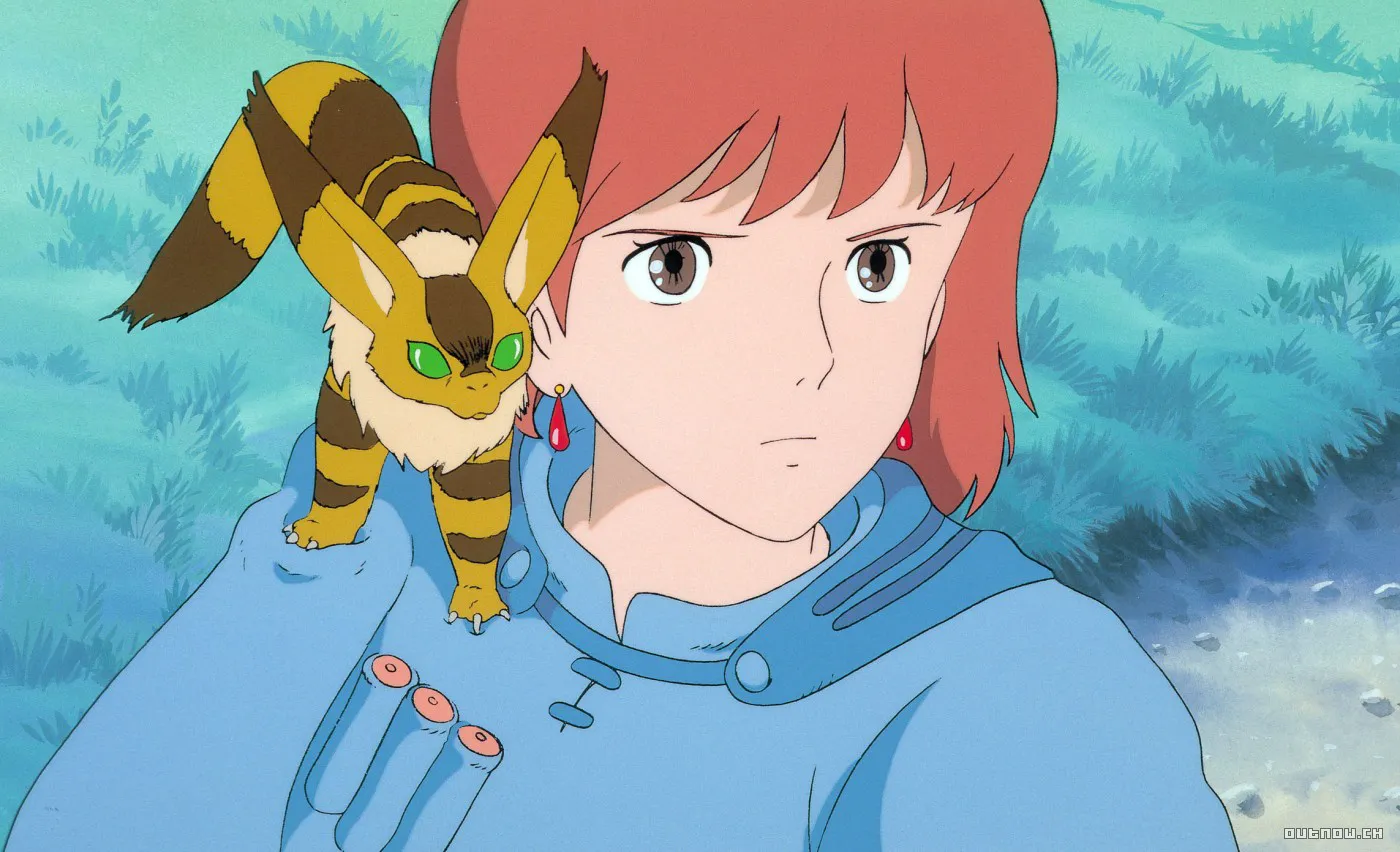

Set a millennium after an industrial civilization’s demise in a bio-weapon-fueled global war, the world is now largely consumed by the Toxic Jungle. Only mutants and colossal insects known as “Ohmu” can survive there. The remnants of humanity, fractured into warring states, cling to the remaining habitable lands. Nausicaä, the young princess of the Valley of the Wind, effectively leads her people as her father, the ruler, is terminally ill. Intelligent and courageous, she seeks to unravel the mysteries of the Jungle and halt its encroachment. However, she must transform from a scientist into a warrior when a neighboring kingdom’s airship crashes in her valley, carrying an ancient superweapon. The warlike neighbors use this as a pretext to invade the peaceful Valley.

It may seem odd to call this a work by an “early Miyazaki,” considering the director was already 43. However, Hayao Miyazaki’s biography dictates that Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was only his second full-length animated film, released in 1984.

The term “Ohmu,” used for the giant insects, translates from Japanese as “king of insects.”

Miyazaki’s Early Influences

During World War II, Miyazaki’s family owned a factory producing parts for military aircraft, instilling in him a lifelong fascination with aviation. Despite this, he pursued a different path. He initially aspired to be a comic book artist, but his passion shifted to animation after seeing The Tale of the White Serpent, Japan’s first full-color animated feature, in 1958.

In 1963, he joined Toei Douga (now Toei Animation), a leading Japanese animation studio. Starting as an artist, he rose to become a key animator. His contributions at Toei included well-known works like Puss in Boots and The Flying Phantom Ship.

Due to their active involvement in union activities, Miyazaki and his colleague Isao Takahata were not favored by the studio heads. In 1971, they left Toei and spent a decade working on animated television series. During this time, Miyazaki made his directorial debut, co-directing with the more experienced Takahata.

From Lupin to Nausicaä

Miyazaki’s solo directorial debut came in 1979 with Lupin the 3rd: The Castle of Cagliostro, based on the Lupin III manga and animated series. He secured this role due to his previous work on the television adaptation.

The success of The Castle of Cagliostro led Tokuma Shoten to propose a collaborative film project. However, the publisher rejected Miyazaki’s initial script ideas, one requiring the purchase of foreign book rights and the other being an original story untested on audiences. Tokuma Shoten suggested that Miyazaki first create a comic based on his second idea to gauge public interest in a post-apocalyptic tale of a world facing ecological disaster. Thus began the Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind project.

The Birth of a Heroine

Miyazaki found the unusual name of his protagonist in Homer’s Odyssey. Nausicaä, the young Phaeacian princess, rescued Odysseus when his ship wrecked near her island. In antiquity, she was credited with inventing the game of ball, a key reason Miyazaki chose her name. He aimed to create a character who was both feminine and masculine – attractive, kind, loving, and compassionate, yet also calculating, decisive, resourceful, fearless, and equally skilled in combat as men, both in hand-to-hand fighting and piloting gliders and aircraft.

Other inspirations included an ancient Japanese tale of a young court lady who preferred caring for insects to her appearance, and renowned Western fantasy and science fiction series like Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings, Ursula K. Le Guin’s Earthsea, and Frank Herbert’s Dune. Miyazaki also drew from real-life ecological disasters, particularly the Minamata Bay mercury poisoning in Japan during the 1950s and 1960s.

Hideaki Anno, later of Gainax studio, a key animator on Royal Space Force: The Wings of Honnêamise, and creator of Neon Genesis Evangelion, was among the animators on Nausicaä. Miyazaki was so impressed with his work that he wanted Anno to join his team permanently, but the young animator preferred working with his peers.

From Manga to Anime

Despite Nausicaä’s origins as an unrealized script proposal, Miyazaki insisted on drawing the comic without considering a potential film adaptation. The publisher agreed, as comics were a more significant business for them. However, after Nausicaä began serialization in Animage magazine in 1982, readers clamored for an animated version of the epic cycle. Amidst growing fan pressure, the publisher convinced Miyazaki to write and direct a full-length film, even though the story was far from complete (the comic ran until 1994, and the film adapted only the first 16 of 59 chapters – less than a third of the 1000-page comic).

As Tokuma Shoten lacked its own animation studio, Miyazaki and producer Takahata entrusted the film to Topcraft, founded in 1972 by former Toei employee Toru Hara. Known for its work with Rankin/Bass Productions (including The Hobbit, The Flight of Dragons, and The Last Unicorn), Topcraft’s experience in creating full-length films, rather than cutting corners in television animation, appealed to the duo. Such studios were rare in Japan at the time, as anime in the 1970s was primarily for television. Later, Topcraft’s artists formed the core of Studio Ghibli, where Miyazaki and Takahata created their subsequent films.

A Masterpiece, But Not Without Flaws

Released in 1984, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind was immediately hailed as an animated masterpiece. Even now, decades later, it frequently appears on “best of” lists, sometimes ranking higher than Miyazaki’s later works. Helen McCarthy and Jonathan Clements, in their “Encyclopedia of Anime,” call it “superb in every respect.” However, this analysis suggests that the second film in Miyazaki’s “full-length canon” is somewhat overrated.

Undeniably, it is a remarkable and grand work. The tight schedule and modest budget (the film was animated in nine months for a million dollars) did not prevent Miyazaki from creating perhaps his most epic work. With thrilling aerial and ground battles, a meticulously crafted post-apocalyptic world with bizarre mutants, unexpected plot twists, and energetic action, Nausicaä has much to commend it, especially when judged by the standards of a Michael Bay film.

This is not an insult. Compared to Hollywood blockbusters of the early 1980s, Nausicaä was a powerful film, comparable in scale only to Star Wars. However, in an era saturated with epics and “triumphs of design,” Nausicaä is interesting not so much for its spectacular dogfights or Nausicaä’s near-unarmed combat against enemy soldiers, but for how Miyazaki handles the characters and their spiritual journeys.

The Problem of Perfection

The title character suffers from a “perfect syndrome.” She is a warrior, scientist, engineer, and leader, excelling in everything. She remains calm in the most difficult situations, accurately assesses the odds of her small state against a superior enemy, and shows mercy to mortal foes. Had she lived in ancient Judea, Jesus Christ would have gone unnoticed, and she would be depicted on icons – that’s how flawless Nausicaä is. In striving to depict a “supergirl” in contrast to the dominant “superboys” in anime and Japanese comics, Miyazaki went too far, creating a character who cannot develop because she is already perfect.

The film’s environmental message was supported by the World Wide Fund for Nature, and Nausicaä opens with their logo.

In the comic, this issue is somewhat mitigated by its ideological complexity, leaving readers little time to dwell on the protagonist as they contemplate the numerous contemporary issues Nausicaä addresses. The film, however, is simpler, essentially a conflict between a barbaric attitude towards nature, embodied by many characters (the ancient superweapon is used to burn the Jungle), and respect for all living things, even the poisonous and deadly, symbolized by Nausicaä.

Therefore, Nausicaä’s inner world becomes the focus of the narrative and viewer’s judgment. When she risks her life to reconcile humans and insects in the finale, it lacks a genuine sense of triumph. Like a robot programmed for good, Nausicaä does what she must, acting as she always does throughout the film – finding the best and least selfish solution. This, admittedly, is boring, albeit worthy of respect and emulation. Even a superheroine should have humanizing flaws.

Compelling Supporting Characters

Other characters are more interestingly conceived. Princess Kushana, Nausicaä’s antagonist (this is a feminist film), dreams not only of conquest but also of defeating the Jungle, in the war against which she lost an arm and, seemingly, her legs. She never appears in public without armor, which also serves as prosthetics. This makes her an ambiguous character deserving of sympathy, but unfortunately, her character is sketched rather than fully developed.

In the American dub of Nausicaä, created for the Disney video release in 2005, Alison Lohman voiced Nausicaä, Uma Thurman voiced Princess Kushana, and Patrick Stewart voiced the wandering warrior Yupa.

The same can be said of other colorful characters, such as the elderly but still vigorous warrior Yupa, who becomes Nausicaä’s advisor and chief supporter after her father’s death. Nausicaä suffers from a typical anime ailment – “serial syndrome,” where a creator accustomed to long and complex narratives overloads a film. Even after all the cuts compared to the comic, the anime Nausicaä is overloaded with events and characters, failing to focus on a few key characters and fully develop them. This overload is not as severe as in some other victims of the “syndrome,” but the film’s script is not perfect, a fact Miyazaki later acknowledged.

Joe Hisaishi’s music, also often praised, is not particularly noteworthy. The film’s symphonic themes are strong, but the synthesizer compositions would only ignite a rural disco. An epic film deserved an epic soundtrack, and Hisaishi’s music sometimes “demeans” Miyazaki’s painted picture rather than emphasizing its power.

A Qualified Recommendation

Does all this mean that Nausicaä is a failure? Absolutely not. As mentioned, the film has much to admire, and its strengths outweigh its weaknesses, especially by the standards of children’s animation, which prioritizes captivating young imaginations over impressing adults with psychological subtleties. Furthermore, it is an influential work that is worth seeing both to understand Miyazaki’s later works and to appreciate the path taken by Japanese animation in recent decades. This analysis simply argues against calling a film that is not truly flawless “perfect,” as it diminishes genuinely impeccable masterpieces.