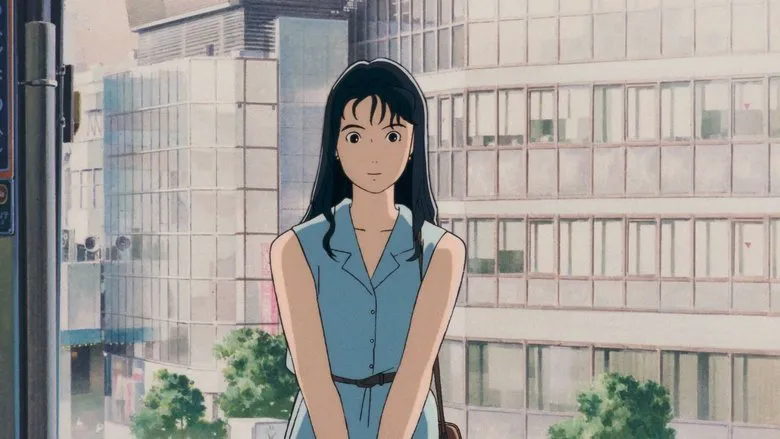

Ocean Waves: A Realistic Anime Drama of Youthful Romance and Self-Discovery

“Ocean Waves” (海がきこえる, Umi ga Kikoeru), while not the most thrilling, offers a realistic and deeply psychological anime drama that explores the romantic and familial experiences of Japanese high school students.

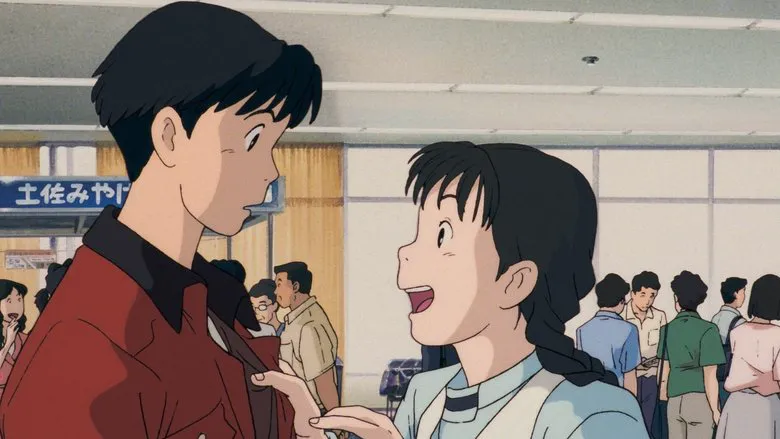

The story follows Taku Morisaki, a college student in Tokyo, as he returns to his hometown of Kochi on the island of Shikoku. His visit is prompted by a desire to see his family and reconnect with former classmates. The journey evokes a sense of nostalgia, leading him to reflect on his final year of high school. He recalls a falling out with his best friend, Yutaka, over a free-spirited girl named Rikako, whom they both admired.

Production Background

Director Tomomi Mochizuki worked on “Ocean Waves” concurrently with the Pierrot studio’s video series, “Here is Greenwood.” After completing both projects, he was hospitalized due to overwork.

In the early 1990s, following the release of “Only Yesterday” and “Porco Rosso,” Studio Ghibli embarked on an experiment. Producers Toshio Suzuki, Hayao Miyazaki, and Isao Takahata gave younger animators the opportunity to create a full-length television film independently, without the guidance of the studio’s established masters. The project was based on Saeko Himuro’s young adult novel “Ocean Waves,” and 34-year-old Tomomi Mochizuki, known for his romantic anime series “Ranma ½” and “Kimagure Orange Road,” was chosen as the director. He was the most senior member of the team animating “Ocean Waves.”

While Ghibli animators provided guidance, the film was primarily animated by Japanese studios J.C. Staff, Madhouse, and Oh! Production.

Ghibli’s executives hoped that the film would be produced quickly and inexpensively, generating enough profit to allow the studio to continue training young talent on projects that weren’t Ghibli’s main productions. However, Mochizuki exceeded both the budget and the deadlines. The audience and critical reception to the film led the studio to avoid working for television and hiring outside directors in the future.

A Hidden Gem or a Flawed Work?

Today, “Ocean Waves” is one of Ghibli’s least-known works, with opinions ranging from “a forgotten treasure of the greatest Japanese animation studio” to “a mediocre film that tarnishes Ghibli’s glorious filmography.” The truth, as often is the case, lies somewhere in between. While not a must-see for every fan of Japanese animation, it’s also not a film to be easily dismissed, especially if you enjoy realistic, arthouse-style melodramas that prioritize insightful observations of human behavior over a fast-paced, engaging plot.

Kochi Castle, which the characters admire at the end of the film, is the best-preserved Japanese castle from the samurai era. It was built in the early 17th century and reconstructed after a fire a century later.

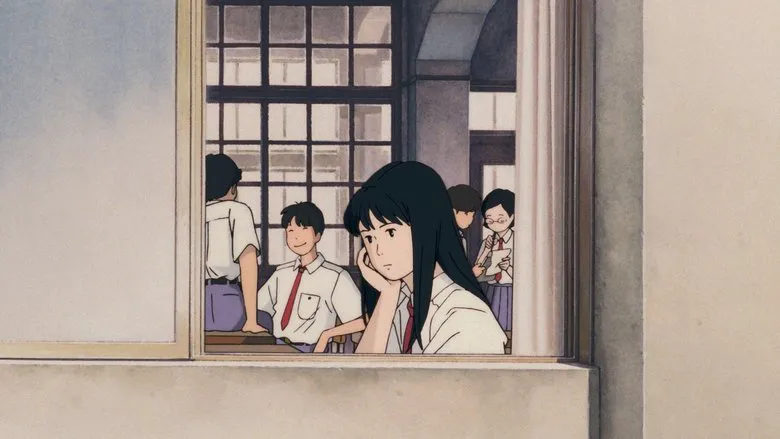

Character-Driven Story

“Ocean Waves” is often described as a story about a high school romantic triangle. However, Yutaka and the “triangular” plot twists play such a minor role in the narrative that it would be more accurate to call the film a dual psychological portrait of Taku and Rikako.

Both main characters are fairly typical for such stories. Taku is a hardworking provincial boy who tries to live according to traditional codes of conduct: being a loyal friend, a reliable comrade, a diligent student, and a worthy son. In contrast, Rikako behaves almost like a sociopath. A native of Tokyo who was brought to Kochi by her mother after a divorce, she looks down on the locals, doesn’t make friends, often lies, tries to manipulate those around her (for example, she tricks Taku and Yutaka into giving her money for a trip to see her father in Tokyo), and instantly switches between anger and charm when necessary. Rikako also disregards social conventions, and she has no problem saying that she’s in a bad mood because she’s having a heavy period or admitting that she spent the night with a guy in a hotel (nothing “happened” between them, but by Japanese standards, it’s still a scandal).

As opposites attract, Taku and Rikako, to their mutual surprise, develop something of a romantic connection. But the director is less interested in this than in the psychology of teenagers on the verge of adulthood – at a time when a person already imagines themselves grown up but still behaves foolishly and childishly. Despite all their obvious differences, Taku and Rikako are both quite selfish, and they find it difficult to see the world through the eyes of others, which creates all the problems they face. These aren’t the most interesting or sympathetic characters, but their lives, their conflicts, and their behavior provoke deep reflections on a wide range of things – from the differences between metropolitan and provincial Japanese residents to how easy it is to attach someone to yourself by not helping them but, on the contrary, demanding help and services from them. And whether Rikako’s actions can be justified by what’s happening in her broken family.

The Ephemeral Nature of Youth

Not content with simply depicting teenage passions, the film concludes two years after graduation, when former classmates who have scattered to colleges reunite. It then becomes clear that much of what they experienced in their final year was a temporary “teenage obsession,” a hormonal surge in a closed school world where every little thing mattered. Taku and Yutaka, who had previously fallen out over Rikako, are once again friends, and the girl who bullied Rikako in school remembers her with nostalgic kindness. Hypocrisy? No, growing up. This is the main lesson of “Ocean Waves” for young viewers to whom the film is intended: “School years can be terrible or wonderful, but when they end and the whole big adult world opens up before you, you will realize how insignificant much of what pleased or annoyed you in childhood was.” And it’s hard to disagree with that.

Technical Aspects

What about the graphics and animation, which have always been Ghibli’s trump card? In “Ocean Waves,” the technical side of the film is the weakest. It’s a mid-budget television film, and it’s far from the studio’s blockbusters – all the corners cut are clearly visible to the naked eye. However, if you compare it with Mochizuki’s previous works outside of Ghibli, the film looks quite decent. And this intimate, conversational story would hardly have benefited from doubling the animation budget.