A charming yet flawed anime adaptation of a nostalgic comic about a Japanese schoolgirl in the 1960s.

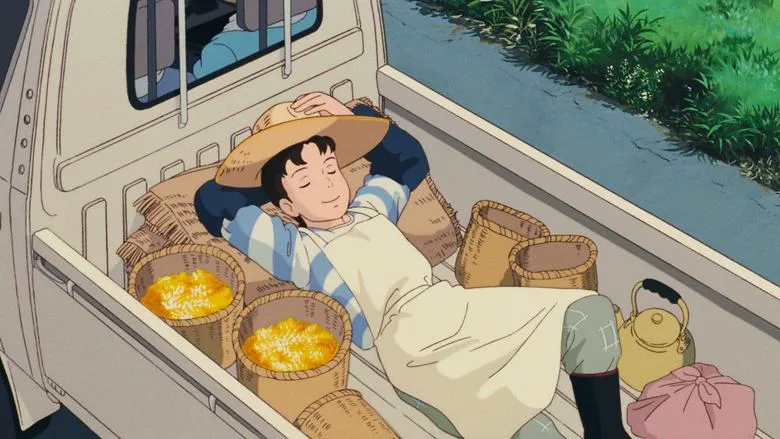

Taeko, as a child, often felt left out because she didn’t have relatives in the countryside. Unlike her classmates, she spent her summer vacations in Tokyo. Years later, thanks to her sister’s marriage, Taeko finally had rural relatives. She began visiting them during her vacations, helping in the fields, enjoying life away from the metropolis, and secretly dreaming of settling down amidst the picturesque meadows and hills.

A Glimpse into Yesterday

“Only Yesterday” holds the unique distinction of being the only Studio Ghibli film not officially released on video in the United States and Canada, despite Walt Disney Corporation possessing all rights for its distribution and translation.

The phenomenal commercial success of “Kiki’s Delivery Service” in 1989 granted both of Studio Ghibli’s leading directors carte blanche for creative experimentation. Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata soon cashed in on this opportunity. By 1992, Miyazaki created “Porco Rosso,” a historical adventure film imbued with a love for old warplanes. In 1991, Takahata adapted the nostalgic, semi-autobiographical, realistic comic “Omohide Poro Poro” (“Only Yesterday” is a translation of the official English title) by screenwriter Hotaru Okamoto and artist Yuko Tone, which chronicled the life of a young girl in the mid-1960s.

In 1991, “Only Yesterday” grossed 1.87 billion yen in the Japanese box office, becoming the highest-grossing Japanese film of the year, both live-action and animated.

Despite its seemingly childish narrative, “Omohide Poro Poro” was written for young women, making its adaptation a risky experiment. Even today, animated series and films in Japan are typically aimed at children, teenagers, and young men, but rarely at young women or housewives.

The Takarazuka Revue, which Taeko’s older sister is fond of in the film, is a renowned Japanese all-female musical theater troupe. It was created as an antithesis to the “noh” and “kabuki” theatrical traditions, where historically all roles were performed by men.

The Tale of Two Taekos

After reading “Omohide Poro Poro”, Takahata was concerned by its collection of separate, unconnected stories. He decided to create a framing story about the now-adult protagonist visiting the countryside on vacation and reminiscing about her childhood while contemplating her future. An elegant narrative solution? Unfortunately, not quite. The two parts of “Only Yesterday” are so disparate that they don’t quite mesh or resonate; they simply coexist. The plot becomes detached from its drama, as the adult Taeko’s story is plot-driven but lacks drama, while the childhood stories are dramatic but lack a cohesive plot.

To justify the heroine’s constant flashbacks, Takahata has her draw a parallel between her two ages at the beginning of the film, suggesting that in both cases, Taeko is on the cusp of a new stage in her life – adolescence or marriage. However, this parallel is tenuous. The transition from child to teenager is a natural process, regardless of feelings or desires, while marriage, relocation, and career changes in the modern world are choices made by women, representing a completely different life and psychological dilemma. The parallel feels forced, stemming from an inability to more elegantly and meaningfully connect the heroine’s past and present experiences.

Worse still, the two narratives in “Only Yesterday” are fundamentally different in structure. The childhood stories are 20% nostalgia for the 1960s and 80% a subtle and profound psychological portrait of a young girl who longs to escape the stuffy and boring Tokyo, experiences something akin to first love, receives her first and last slap from her father, grapples with her hatred for a school bully, and dreads her impending menstruation.

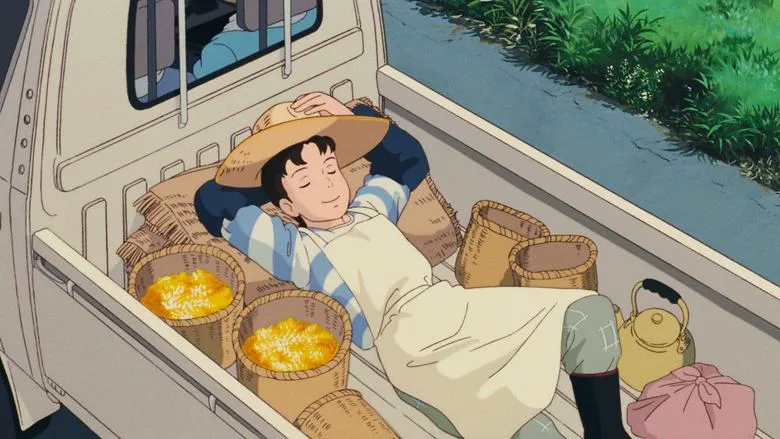

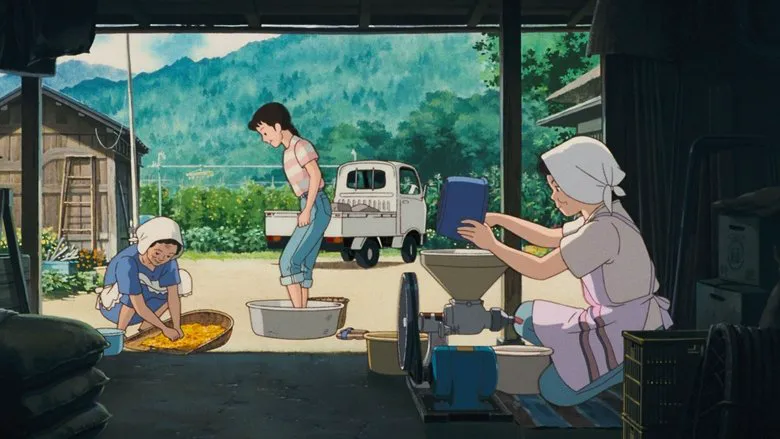

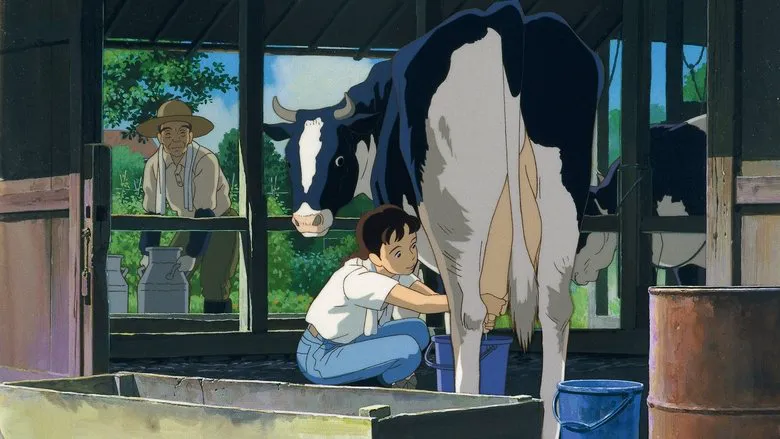

In contrast, the adult Taeko’s story is 5% psychological insight, 15% a budding romance with a young farmer who is related to her sister’s husband, and 80% blatant propaganda for rural life. Even Soviet directors who made films about the joys of collective farms would have hesitated to so openly advocate abandoning “office drudgery” and moving to the countryside to milk cows, plant rice, and harvest saffron. Takahata describes the latter in such detail that “Only Yesterday” feels less like an animated film and more like a report for the Discovery Channel. Consequently, the film feels disjointed, like comparing apples and oranges.

Why is this the case? Perhaps because Takahata, as a man, hesitated to delve further into the nuances of “female logic” that were explored in the comic created by women. In his original part of the film, he abandoned the pronounced psychological depth of the script fragments borrowed from “Omohide Poro Poro.” This might have worked if the adult Taeko were an episodic character, like the narrator and his grandson in “The Princess Bride.” However, in Takahata’s film, she is almost as important as the young Taeko, making the complete disconnect between the styles and essence of the two narratives immediately apparent to the thoughtful and attentive viewer. And, of course, social advertising does not enhance artistic cinema, especially when both main characters in this part of the film, Taeko and her potential suitor, compete to praise life in the countryside. It’s less like social advertising and more like a home shopping channel ("And do you know what our food processor can do?.. “Yes, and much more!”)…

Cultural Nuances and Universal Themes

Another drawback, from the perspective of a viewer unfamiliar with Japanese culture, is the film’s reliance on specific cultural references. Takahata cannot be faulted for creating a film for his compatriots, but this can make the film less accessible to international audiences. “Only Yesterday” often requires detailed online commentary to fully understand. For example, why does Taeko’s father slap her when she runs outside without shoes? (For Mr. Okajima’s generation, going outside without shoes was as shameful as going outside in underwear). While many of the problems the heroine faces are universal, and some aspects are more relatable to certain cultures, the film contains enough uniquely Japanese and 1960s-specific details to make a viewing without commentary incomplete.

Endearing Despite Its Flaws

Despite these issues, the film and its heroine remain endearing, and the excursions into Taeko’s past are filled with insightful and interesting observations. These excursions are undeniably the best and almost flawless part of the film, save for the aforementioned need for explanations. In turn, the glorification of rural labor in the adult part of the film is depicted with a fervent zeal and meticulous attention to detail, and some frames from these fragments are so striking and picturesque that one wants to print them and hang them on the wall as pastoral paintings.

The film features music by Romanian flautist Gheorghe Zamfir, often hailed as the world’s greatest master of the pan flute. His compositions can be heard in Hollywood films such as “Once Upon a Time in America,” “The Karate Kid,” and “Kill Bill,” as well as in the French hit “The Tall Blond Man with One Black Shoe.”

The music chosen by the director is captivating and impressive – strangely enough, from the repertoire of Hungarian, Bulgarian, and Romanian musicians who processed folk motifs. It would seem that European music should not be suitable for a Japanese village. But farming is farming everywhere, whether in Hungary or Japan. They plant different crops there, but people in the countryside are similar in spirit everywhere, and therefore Western peasant music is quite compatible with the peasantry of rice and saffron.

In conclusion, it is understandable why “Only Yesterday” became a hit in Japan – nostalgia softens and clouds the eyes, making one forgive the shortcomings of nostalgic cinema and concentrate on its merits (accuracy of observations, charm of characters, visual and musical delights). We, however, look at “Only Yesterday” from the outside and therefore see both its significant advantages and its obvious and not always forgivable disadvantages.