Perfect Blue: A Psychological Anime Thriller

A gripping psychological anime thriller about a former pop idol who transitions into acting and finds herself entangled in a series of disturbing and bloody events.

Mima Kirigoe, the lead singer of a moderately successful J-pop group, announces her departure from the music scene to pursue a career in television acting. While her fans are dismayed, Mima’s managers support her decision, believing she has greater earning potential as a TV star. Initially, Mima secures only minor roles, but the series’ writers later decide to cast her as the main antagonist – a mentally unstable rape victim. As Mima “tarnishes” her once-pure image, people around her begin to die, and Mima, increasingly losing touch with reality, starts to suspect that she is committing crimes not only on screen but also in real life.

While the title “Истинная грусть” (True Sadness) has become established, the film’s original title, Perfect Blue (used in both America and Japan), refers to the color of a clear, cloudless sky, symbolizing inner peace.

Unlike Soviet and American animation, Japanese animation is renowned for its diverse genres. However, even within this landscape, the psychological thriller Perfect Blue stands out as an exceptional work. Originally conceived as a direct-to-video series based on Yoshikazu Takeuchi’s novel, the production company faced setbacks due to the Kobe earthquake in 1995. The remaining funds were allocated to create a full-length animated film, released in 1997. Although initially intended for video, it eventually reached theaters and garnered acclaim at several genre festivals.

Satoshi Kon’s Directorial Debut

Thanks to the involvement of Katsuhiro Otomo, the manga artist and creator of Akira, as a consultant, Perfect Blue marked the directorial debut of Satoshi Kon, Otomo’s former assistant. This single film was enough to secure Kon’s place among the most distinguished Japanese animators. He later solidified his reputation with works like Millennium Actress, Tokyo Godfathers, Paranoia Agent, and Paprika. Sadly, Kon passed away prematurely in 2010 at the age of 46 due to cancer.

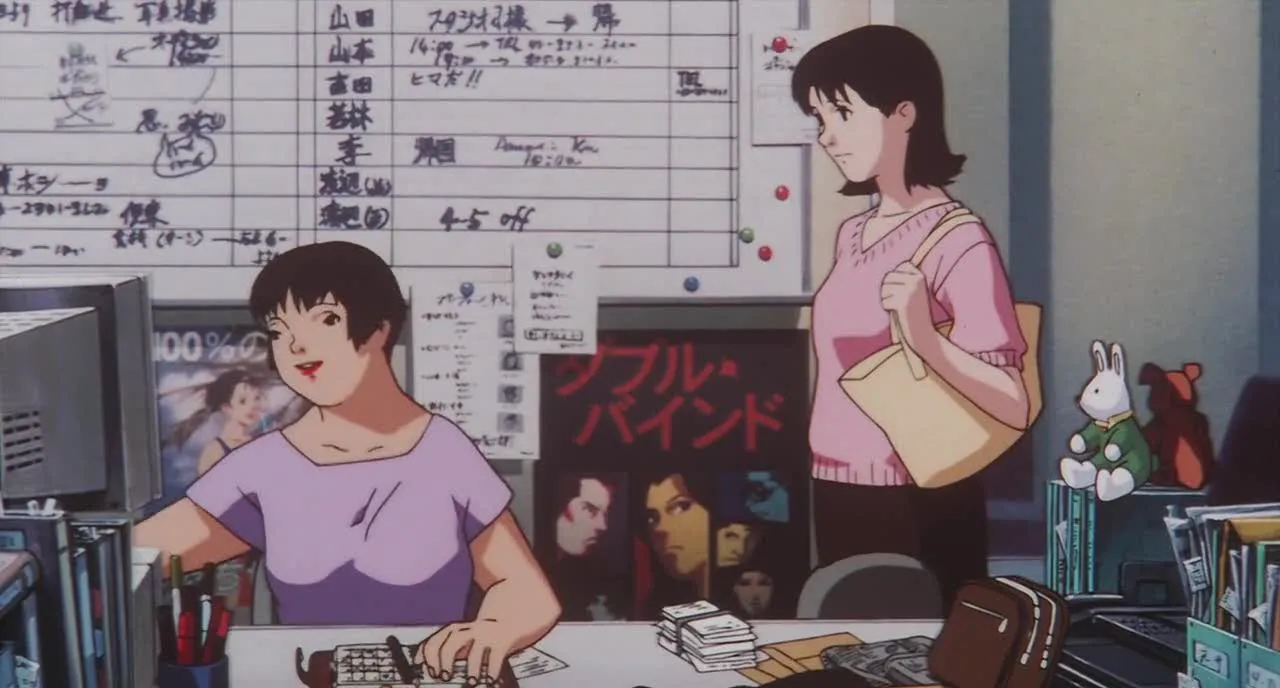

When working on the film, Satoshi Kon researched the lives of pop singers, but he always cautioned foreign fans against interpreting Perfect Blue as a true representation of the Japanese entertainment industry’s behind-the-scenes realities.

Visuals and Narrative Depth

From a graphic and animation standpoint, Perfect Blue isn’t the most visually stunning work from the esteemed Madhouse studio. The film’s limited budget is evident in the numerous static or near-static shots, typical of budget-conscious Japanese productions, where meticulously detailed backgrounds attempt to mask the lack of movement. While there are certainly visually captivating moments (beyond the scenes of Mima’s nudity, whether in the rape scene or her near-victimization), this isn’t a film to be watched silently solely for the animation’s artistry. Perfect Blue’s greatness, often compared to Hollywood’s psychological masterpieces, lies in its intricate plot and script, and its sophisticated interplay of multiple layers of reality and illusion.

Mima is a small-town girl portraying a city dweller (she typically speaks standard Japanese but switches to her native dialect when talking to her mother), who is portraying a former pop star turned actress, now playing a mentally unstable character on TV who alternately believes herself to be her own sister. But let’s not delve into spoilers.

Perfect Blue inspired Darren Aronofsky when he made Requiem for a Dream and Black Swan.

Blurring Realities

Confusing? Absolutely! This is precisely why Mima unravels both in her TV show and in her personal life. Her realities overlap and clash because Mima the actress desires to be a liberated adult woman, taking on provocative roles and posing for men’s magazines, while Mima the singer clings to the past, when she embodied a naive virgin and sang “pure” songs about innocent love. The former Mima is supported by her new colleagues, while the latter is championed by her fans. This internal conflict renders her psyche incredibly vulnerable and prone to hallucinations and memory lapses.

In 2002, a live-action adaptation of Perfect Blue was released in Japan, adhering more closely to Takeuchi’s novel than Kon’s animated film. However, critics deemed it unsuccessful and significantly inferior to Kon’s version.

While Mima’s circumstances are unique, her internal struggle resonates with many, especially women, who are often pressured by modern society to be both “madonnas” and “whores.” Satoshi Kon always maintained that his film is simply a coming-of-age story disguised as a thriller. However, many critics rightly see Perfect Blue as a sharp critique of contemporary attitudes toward young women. Every character in the film seizes the opportunity to scold Mima from their own perspective and impose their vision of life upon her. And for the Japanese, it’s generally difficult to disregard the opinions of others and live according to one’s heart. However, Mima herself doesn’t truly know what her heart desires, which is why she experiences hallucinations of her pop star alter ego.

When the hallucinated Mima begins to appear regularly on screen, perceptive viewers realize why Perfect Blue benefited from being animated rather than live-action. Mima’s pop incarnation is dressed in a vibrant stage costume, and she floats weightlessly across rooftops, seemingly defying gravity. If both characters were played by an actress, it would be evident that one is real and the other is created with special effects. In the animated film, both characters are drawn, and neither is more real than the other, at least visually.

__

This allows Kon to increasingly blend realities (the “real” reality, the reality of the TV show, Mima’s hallucinations) as the climax approaches, disorienting viewers and making them question what they see, even when it seems plausible. As a result, the audience can not only understand what Mima is going through but also deeply empathize with her confusion, terror, and emotional trauma. This, arguably, is the primary artistic goal of any ambitious psychological film.

To heighten the suspense for Mima and the audience, and to make the ending more intense, violent crimes begin to occur around her. This provides a formal reason to classify Perfect Blue as a detective story. However, the film isn’t intended for those who enjoy examining clues and evaluating suspects alongside on-screen detectives. Firstly, there are no detectives in the film. Secondly, the perpetrator can be identified long before the film’s resolution, but this doesn’t diminish Perfect Blue’s impact. Kon created a suspenseful film about the intersection of realities and illusions, not about who held the knife at what moment. In fact, the film doesn’t provide a definitive answer to the latter question, and fans still debate what happened in the “real reality.” However, for Japanese animation, this isn’t a flaw but a common practice – focusing on what truly matters (in this case, Mima’s inner turmoil) and leaving secondary details for viewers to interpret. After all, not everything needs to be spoon-fed.

Finally, Perfect Blue touches on the theme of cyberstalking. The film forces the protagonist to navigate the Internet and discover a website where an unknown perpetrator (or the girl’s alter ego?) keeps a diary in Mima’s name, demonstrating knowledge of the most minute details of her life. Takeuchi’s book contained nothing of the sort – Kon conceived this plot element when he himself “settled” on the Web. Nothing special these days, but note that Kon’s additions are absolutely reliable. What a striking and pleasant contrast to Hollywood films and series, where even now the Internet is not always shown as it really is!