A wondrous, magical anime fairy tale about a little girl learning to navigate adulthood in an astonishing world of otherworldly beings.

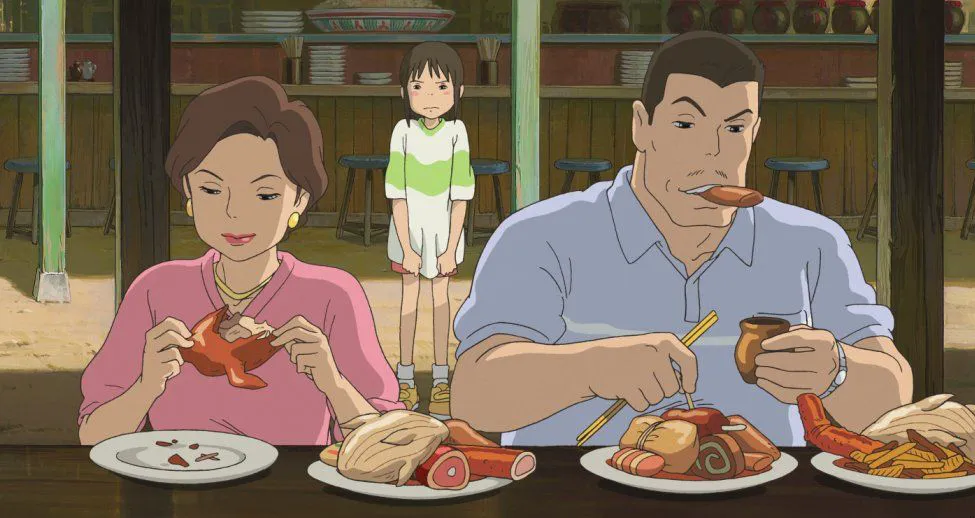

Ten-year-old Chihiro is moving to a new house with her parents. Along the way, her father decides to take a shortcut and drives down an old road, which, as it turns out, leads not to residential buildings, but to an abandoned resort built around a luxurious multi-story bathhouse. When freshly prepared and very appetizing food is discovered on one of the counters, Chihiro’s parents immediately devour the dishes and, to the girl’s horror, turn into pigs. It turns out that the resort is not abandoned – it is inhabited by otherworldly creatures of all shapes and sizes, who at night serve venerable nature deities gathering from all over Japan. Since humans can only be in the spirit world if they are occupied with work, Chihiro is forced to get a job as a cleaner in the bathhouse and signs a contract with the owner of the establishment, the cunning and greedy witch Yubaba.

The film’s title is a reference to an ancient Japanese legend that otherworldly beings sometimes kidnap children and return them several days later, usually to a temple associated with the deity of those beings.

After drawing two full-length animated films in the 1980s, primarily aimed at girls (“My Neighbor Totoro” and “Kiki’s Delivery Service”), director Hayao Miyazaki decided to start the new century with another “female” picture that would fill the resulting age gap. “Totoro” was drawn for preschoolers and elementary school students, “Delivery Service” – for high school teenagers, and girls aged 10-12 were left uncovered, and the director, who knew several “young ladies” of this age from his friends’ families, believed that he could not retire until he released a suitable film for them.

In the American dub of “Spirited Away,” the main character was voiced by Daveigh Chase – Lilo from the Disney cartoon “Lilo & Stitch.” John Lasseter from Pixar, a big fan of Miyazaki, was the executive producer of the translation.

At first, Miyazaki considered adapting a popular comic book. But the comics published in the magazines that his little acquaintances read were, as a rule, romantic stories – fascinating, but, in the director’s view, not developing girls and not offering them worthy role models. The director did not want to show first love. He wanted to show how a capricious, cowardly, lazy girl, getting into trouble, finds the mental strength to overcome her shortcomings and in just a few days to grow up – to become responsible, serious, caring and hardworking. Miyazaki hoped that, seeing such a heroine, very similar to them, girls would believe in their own abilities and begin to dream not only about how to find a “prince” and get married successfully. Of course, his films had previously featured admirable girls and women. But, with the exception of the girls from “Totoro,” those were idealized heroines with whom ordinary little Japanese girls found it difficult to identify.

The film was completely drawn on computers, but only with minimal use of 3D CG graphics.

Trying and rejecting one potential plot after another, Miyazaki noticed that he kept returning to the theme of the traditional Japanese bathhouse. These establishments, often built on revered hot springs, always seemed to the director a bizarre and mysterious place where people cleanse not only their bodies, but also their souls. In the bathhouse in Miyazaki’s “small homeland” there was an eternally locked door, and the director repeatedly came up with stories about where this door might lead. And one day, from these fantasies, a story was born about a secret resort bathhouse for respected ghosts, spirits and deities. After all, people are not the only ones who like to relax after a hard day’s work – or a hard year’s work!

The design of the bathhouse in “Spirited Away” was inspired by the current main building of the bath complex at the Dogo hot springs in Matsuyama. These springs have been famous since ancient times. They are mentioned in the “Man’yoshu,” the oldest anthology of Japanese poetry, compiled in the 8th century AD.

Thus began the script for “Spirited Away” – an original composition by Miyazaki, which, however, is filled with references to Japanese mythology and literary classics. Thus, the main character’s попадание in a bizarre inhuman reality immediately brings to mind “Alice in Wonderland,” and in the witch who turns people into pigs with the help of a magic treat, it is easy to recognize Circe from Homer’s “Odyssey.” Recall that Miyazaki had already quoted the “Odyssey” in “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind,” giving the title character a Homeric name. Of course, there are much more hints of national tradition in “Spirited Away,” and if desired, you can write a whole treatise on the connection of the film with Japanese culture.

Some of the characters’ names are, in essence, their descriptions. Thus, “Yubaba” translates as “bath witch,” and the name of the stoker Kamaji means “old man from the boiler room.”

After the triumph of “Princess Mononoke,” which was amazing even for Miyazaki, the director was already drawing his next picture as not an outstanding animator, but a “living god,” and “Spirited Away,” released in 2001, really turned out to be divine. Well, almost divine, because they cannot be called “infallible.” For example, the film in some scenes relies on implausible coincidences and rules of the magical world that are beneficial to the heroine, but logically inexplicable. What, for example, justifies the fact that Yubaba swore to give work to everyone who asks for it? Is this beneficial for her establishment? And how likely is it that Chihiro in the bathhouse stumbles upon, probably, the only magical creature with whom she has a long-standing, accidentally established connection? And, by the way, if Yubaba turns people who accidentally wander into the bathhouse into pigs, and her subordinates put the piglets into sausage, then shouldn’t the witch be an absolute villain, and not a creature to whom the director tries to evoke sympathy in the course of the action?

The budget of “Spirited Away” was 1.9 billion yen ($19 million), and worldwide box office – $300 million.

These, however, are only small spots, visible only to an attentive adult viewer, on the brightest sun called “Spirited Away.” Many critics consider this film the best in the history of Japanese animation. And although we put “Princess Mononoke” a little higher in the ranking, since we consider it a deeper and more dramatic canvas, we completely agree with all the laudatory reviews of “Spirited Away” that have been published since 2001.

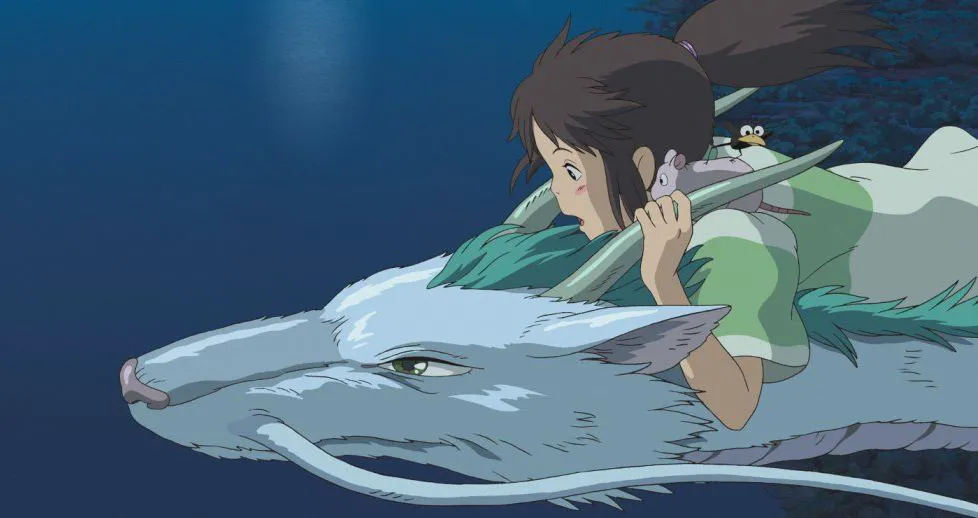

Stunning animation and detailed graphics, luxurious design, colorful supporting characters, the main character, whose transformation during the film can only be compared with the transformation of Sarah Connor in “Terminator” from a simple waitress into the savior of humanity… As well as mysticism, magic, soulfulness, Japanese religiosity, unobtrusive mentions of ecology… And, of course, a fascinating and dynamic plot with several unpredictable twists. And also a pinch of romance. Miyazaki did not include a full-fledged “first love” in the picture, but still did not forget that 10-year-old Japanese girls like stories with the participation of attractive “princes” (in “Spirited Away” this is a dragon turning into a boy – the spirit of a small, but turbulent river).

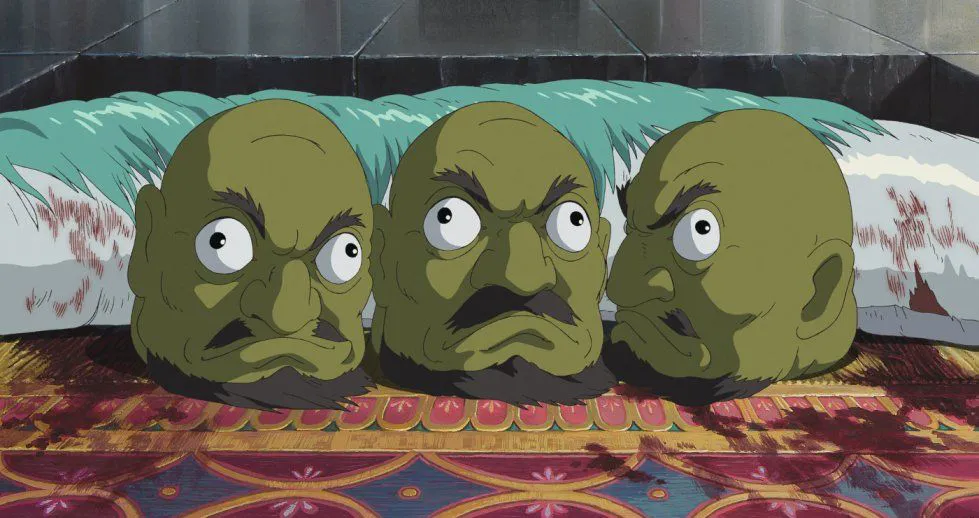

It seems that a whole book can be written about the great and small merits of the film, and it is very difficult to choose the main one among them. Maybe it’s the amazing combination of the mystery of the bathhouse for deities with its satirical recognizability as an “ordinary” business with thieving employees and screaming managers? Or maybe it’s the feeling that “Spirited Away,” for all its scope, touches on only a small fraction of the wonders of the spirit world and that Miyazaki, if he wanted to, could draw films about this world for years without ever repeating himself and revealing all its new secrets? Or is it the kindness of the director and his love for his homeland, for its history and culture, which manifests itself in every frame, which, however, does not contradict Miyazaki’s progressiveness and his desire to see girls and women not only as housewives, but also as employees and bosses?

In a word, “Spirited Away” is a masterpiece, and soon after the release of the picture, the whole world recognized this. First, the film conquered Japan (“Spirited Away” became the first film in history to gross more than $200 million before its release in the American box office), and then received the “Golden Bear” of the Berlin Film Festival and an “Oscar” for best animated feature film. Foreign critics showered it with praise, and anime fans dreamed that the stunning success of “Spirited Away” would force Japanese animation to be included in the world mainstream on a par with Hollywood feature films and cartoons.

As we now know, this did not happen, but Miyazaki was not to blame for this. It’s just that in such cases, one man is not a warrior in the field, and the Japanese animation industry did not support its classic with a stream of family “blockbusters” that, if not equivalent, would be comparable in essence, which could rush into the breach in the international perception of anime broken through by Miyazaki. Well, зато she has kept her face as an “industry for fans.” This is also worth a lot.