An Exquisite Animated Fairy Tale: A Young Girl’s Journey to Adulthood in a World of Spirits

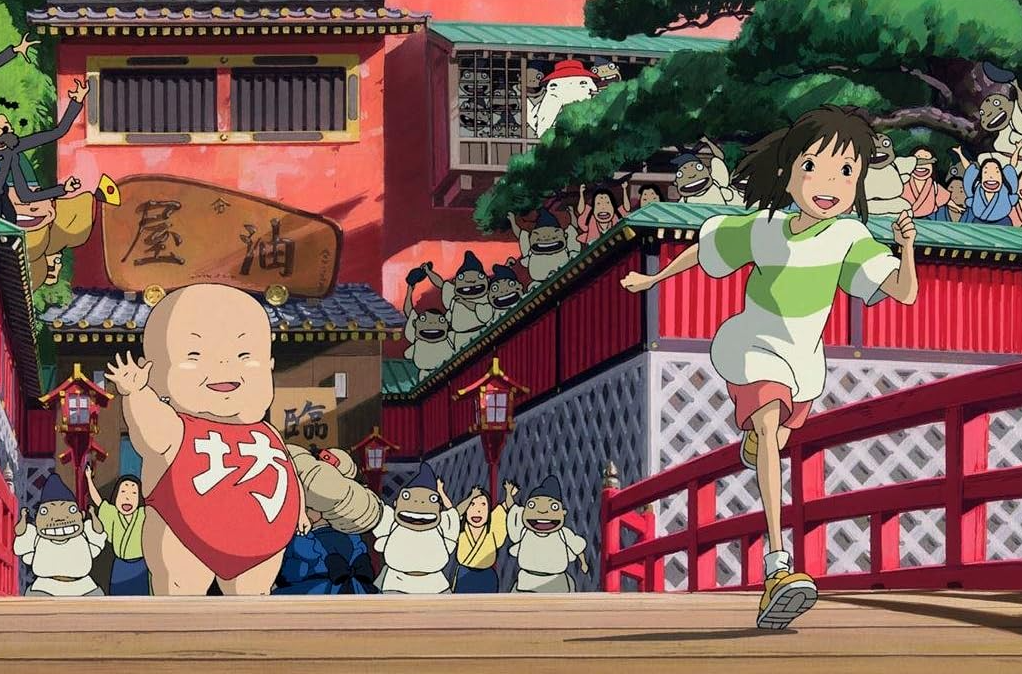

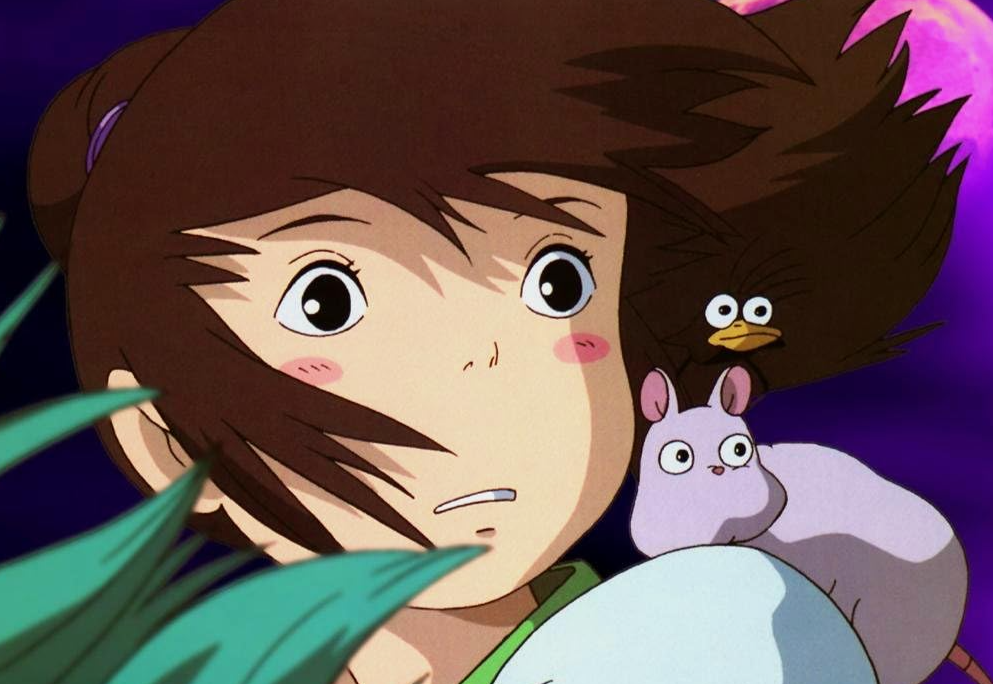

Ten-year-old Chihiro is moving to a new home with her parents. Along the way, her father decides to take a shortcut, leading them to an old road that turns out to lead not to houses, but to an abandoned resort built around a luxurious, multi-story bathhouse. When they discover freshly cooked and appetizing food at one of the stalls, Chihiro’s parents immediately devour it and, to her horror, transform into pigs. It turns out that the resort is not abandoned – it is inhabited by otherworldly beings of all shapes and sizes, who at night serve the esteemed nature deities gathering from all over Japan. Since humans can only stay in the spirit world if they are occupied, Chihiro is forced to work as a cleaner in the bathhouse and signs a contract with the establishment’s owner, the cunning and greedy witch Yubaba.

The film’s title alludes to an ancient Japanese legend that otherworldly beings sometimes kidnap children and return them a few days later, usually to a temple associated with the deity of those beings.

The Genesis of a Classic

Having created two feature-length animated films in the 1980s primarily aimed at girls (“My Neighbor Totoro” and “Kiki’s Delivery Service”), director Hayao Miyazaki decided to start the new century with another “female” picture that would fill the resulting age gap. “Totoro” was made for preschoolers and elementary school students, “Delivery Service” was for high school teenagers, and girls aged 10-12 were left unaddressed. The director, who knew several “young ladies” of this age from his friends’ families, believed that he could not retire until he released a film suitable for them.

In the American dub of “Spirited Away,” the main character was voiced by Daveigh Chase – Lilo from the Disney cartoon “Lilo & Stitch.” John Lasseter from Pixar, a big fan of Miyazaki, was the executive producer of the translation.

From Comics to Bathhouses: Finding the Right Story

At first, Miyazaki considered adapting a popular comic book. However, the comics published in magazines read by his young acquaintances were usually romantic stories – engaging, but, in the director’s view, not developing girls or offering them worthy role models. The director did not want to show first love. He wanted to show how a capricious, cowardly, lazy girl, finding herself in trouble, finds the inner strength to overcome her shortcomings and, in just a few days, grow up – becoming responsible, serious, caring, and hardworking. Miyazaki hoped that, seeing such a heroine, very similar to them, girls would believe in their own abilities and start dreaming not only about finding a “prince” and getting married successfully. Of course, his films had previously featured admirable girls and women. But, with the exception of the girls from “Totoro,” those were idealized heroines with whom ordinary young Japanese women found it difficult to identify.

The film was entirely drawn on computers, but with only minimal use of 3D CG graphics.

Trying and rejecting one potential plot after another, Miyazaki noticed that he kept returning to the theme of the traditional Japanese bathhouse. These establishments, often built on revered hot springs, always seemed to the director a peculiar and mysterious place where people cleanse not only their bodies but also their souls. In the bathhouse in Miyazaki’s “small homeland,” there was a perpetually locked door, and the director often spent his leisure time inventing stories about where that door might lead. And one day, from these fantasies, a story was born about a secret resort bathhouse for respected ghosts, spirits, and deities. After all, humans aren’t the only ones who like to relax after a hard day’s work – or a hard year!

The design of the bathhouse in “Spirited Away” was inspired by the current main building of the Dogo Onsen bathhouse complex in Matsuyama. These springs have been famous since ancient times. They are mentioned in the “Man’yoshu,” the oldest anthology of Japanese poetry, compiled in the 8th century AD.

Influences and Inspirations

Thus began the development of the “Spirited Away” script – an original work by Miyazaki, which, however, is filled with references to Japanese mythology and literary classics. For example, the main character’s entry into a bizarre, non-human reality immediately evokes “Alice in Wonderland,” and the witch who turns people into pigs with the help of a magical treat easily resembles Circe from Homer’s “Odyssey.” Recall that Miyazaki had already quoted the “Odyssey” in “Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind,” giving the title character a Homeric name. Of course, there are far more allusions to national tradition in “Spirited Away,” and one could write an entire treatise on the film’s connection to Japanese culture.

Some of the characters’ names are essentially their descriptions. For example, “Yubaba” translates to “bathhouse witch,” and the name of the stoker Kamaji means “old man from the boiler room.”

A Masterpiece, Imperfectly Divine

After the amazing triumph of “Princess Mononoke,” even for Miyazaki, the director was already drawing his next picture as not just an outstanding animator, but a “living god,” and “Spirited Away,” released in 2001, truly turned out to be divine. Well, almost divine, because it cannot be called “infallible.” For example, the film in some scenes relies on implausible coincidences and rules of the magical world that are beneficial to the heroine but logically inexplicable. What, for example, justifies the fact that Yubaba vowed to give work to everyone who asks for it? Is this beneficial for her establishment? And how likely is it that Chihiro in the bathhouse stumbles upon, probably, the only magical creature with whom she has a long-standing, accidentally established connection? And, by the way, if Yubaba turns people who accidentally wander into the bathhouse into pigs, and her subordinates turn the piglets into sausage, then shouldn’t the witch be an absolute villain, and not a creature to whom the director tries to evoke sympathy during the course of the action?

The budget for “Spirited Away” was 1.9 billion yen (19 million dollars), and worldwide gross was 300 million dollars.

These, however, are only small spots, visible only to the attentive adult viewer, on the brightest sun called “Spirited Away.” Many critics consider this film the best in the history of Japanese animation. And although we put “Princess Mononoke” a little higher in the ranking, because we consider it a deeper and more dramatic canvas, we completely agree with all the accolades for “Spirited Away” that have been published since 2001.

Why “Spirited Away” Resonates

Stunning animation and detailed graphics, luxurious design, colorful supporting characters, the main character, whose transformation during the film can only be compared with the transformation of Sarah Connor in “Terminator” from a simple waitress into the savior of humanity… And also mysticism, magic, soulfulness, Japanese religiosity, unobtrusive mentions of ecology… And, of course, an engaging and dynamic plot with several unpredictable twists. And also a pinch of romance. Miyazaki did not include a full-fledged “first love” in the picture, but still did not forget that 10-year-old Japanese girls like stories with the participation of attractive “princes” (in “Spirited Away” this is a dragon turning into a boy – the spirit of a small but turbulent river).

It seems that an entire book could be written about the large and small merits of the film, and it is very difficult to choose the main one among them. Maybe it’s the amazing combination of the mystery of the bathhouse for deities with its satirical recognizability as an “ordinary” business with thieving employees and loud managers? Or maybe it’s the feeling that “Spirited Away,” for all its scope, touches only a small fraction of the wonders of the spirit world and that Miyazaki, if he wanted, could spend years drawing films about this world, never repeating himself and revealing all its new secrets? Or is it the kindness of the director and his love for his homeland, for its history and culture, which, however, does not contradict Miyazaki’s progressiveness and his desire to see girls and women not only as housewives, but also as employees and bosses, manifested in every frame?

In a word, “Spirited Away” is a masterpiece, and soon after the film’s release, the whole world recognized this. First, the film conquered Japan (“Spirited Away” became the first film in history to gross more than 200 million dollars before its release in the American box office), and then received the “Golden Bear” of the Berlin Film Festival and an “Oscar” for best animated feature film. Foreign critics showered it with praise, and anime fans dreamed that the stunning success of “Spirited Away” would force Japanese animation to be included in the world mainstream on a par with Hollywood feature films and cartoons.

As we now know, this did not happen, but Miyazaki was not to blame for this. It’s just that in such cases, one person is not a warrior in the field, and the Japanese animation industry did not support its classic with a stream of if not equivalent, then comparable in essence family “blockbusters” that could rush into the breach in the international perception of anime broken through by Miyazaki. Well, at least she kept her face as an “industry for fans.” This is also worth a lot.