Tales from Earthsea: A Disappointing Animated Debut

Goro Miyazaki’s first foray into feature-length animation is a misstep, an unsuccessful attempt to bring Ursula K. Le Guin’s classic fantasy cycle to the screen.

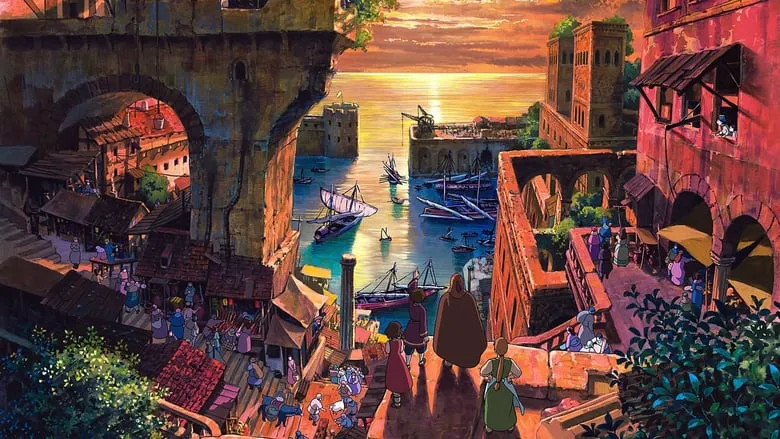

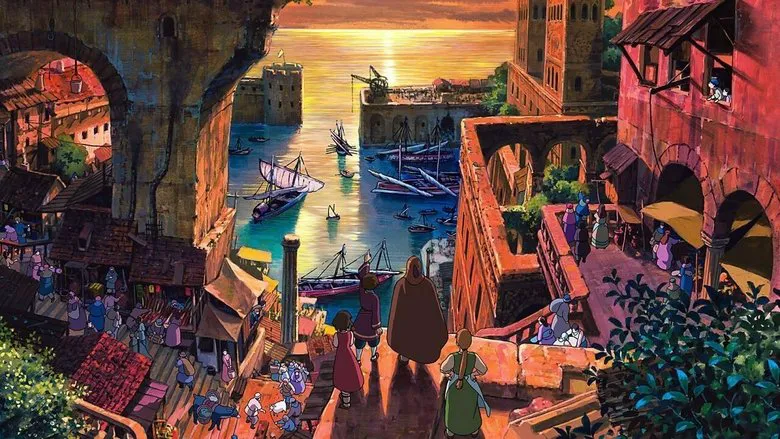

Strange misfortunes plague the lands of Earthsea. Crops wither from drought, people and animals fall ill, and wizards lose their spells and magical power. Suddenly, Prince Arren, a 17-year-old, murders his father, the King, and flees the palace with a magical sword he cannot unsheathe. Wandering through the desert, the young man encounters a solitary old traveler, who turns out to be the Archmage known as Sparrowhawk. The wizard has embarked on a journey to find the source of Earthsea’s suffering. Together, Arren and Sparrowhawk reach a large city, near which the dark mage Cob resides in his castle, seeking eternal life through forbidden sorcery.

In the Japanese version of the film, the character of Cob is voiced by actress Yuko Tanaka. However, Cob is male, and in other versions of the film, the role is voiced by male actors. For example, Willem Dafoe played Cob in the English dub.

Le Guin’s Hesitation and Ghibli’s Gamble

The renowned American author Ursula K. Le Guin had for decades refused all offers to buy the rights to adapt her “Earthsea” fantasy cycle. Among those turned down was the great Japanese animator Hayao Miyazaki. He approached Le Guin in the early 1980s, when he was transitioning from television series to feature-length anime films, but the writer refused, as she had no idea who he was and did not want the serious, profound “Earthsea,” which touched on complex issues, to be turned into a “cartoon like Disney.”

Hayao Miyazaki and Goro Miyazaki had a falling out at the beginning of work on the film because Goro once said at a studio meeting: “If it doesn’t work out, I’ll go back to working at the museum.” Hayao replied that if you take on a responsible project, you have to give it your all and not even think about a “backup plan.” After that, they did not speak until the film was released.

Twenty years later, when Miyazaki received an Oscar for “Spirited Away” in 2002, Le Guin stated that the Japanese director was the only one she would trust to adapt “Earthsea.” The writer’s words were relayed to Studio Ghibli, and its head, Toshio Suzuki, soon signed a contract with Le Guin. However, Hayao Miyazaki was busy with “Howl’s Moving Castle” at the time, and Suzuki made an unexpected decision. He entrusted the direction to Goro Miyazaki, the director’s eldest son. The 36-year-old Goro had artistic talent but had never worked in animation or the screen entertainment industry. Before “Tales from Earthsea,” released in 2006, his specialty was planning gardens and parks. Since 2001, he had been the director of the Ghibli Park-Museum in western Tokyo.

“Tales from Earthsea” and its director, Goro Miyazaki, were awarded the Japanese “Golden Raspberry,” an “award” for the worst films and worst directors of the year.

A Missed Opportunity

Why did Suzuki settle on Goro? First, he liked the storyboards that Miyazaki Jr. had drawn for the film when he was initially brought in as a consultant. And secondly, the producer had no particular choice. Ghibli had always suffered from being created as a “pocket company” for Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata, serving two brilliant creators and not providing ambitious animators with room for career growth. Therefore, artists with leadership qualities either did not stay at the studio or did not go to work at Ghibli at all. Of course, it would have been possible to hire a director from outside. But Suzuki trusted a “relative” with a famous last name. As we now know, he was wrong.

The film cost $22 million to make and grossed $69 million worldwide.

An Unconventional Adaptation

Ask yourself, how would you adapt a cycle of five novels? Obviously, you would start at the beginning – with the 1968 book “A Wizard of Earthsea,” which introduced readers to the young sorcerer Sparrowhawk and the amazing world of magic and dragons around him. At worst, you could choose the second novel, “The Tombs of Atuan,” for the adaptation, as it features not only the main character (an older but still young Sparrowhawk) but also the main heroine – the young priestess Tenar, forcibly compelled to serve the sinister spirits hiding in the darkness of the underground labyrinth. Particularly decisive screenwriters could try to combine “The Wizard” and “The Tombs” into one narrative. In any case, the central character of the film should have been Sparrowhawk – the main character of four of Le Guin’s five novels, whose spiritual evolution makes up the lion’s share of their narrative.

Ged in the film looks darker than other characters. This corresponds to Ursula Le Guin’s intention, who does not like “traditional white protagonists” and often gives her main characters an “ethnic” appearance. Sparrowhawk in her books has brown skin.

Miyazaki, however, based his film on the third and fourth books of the cycle, “The Farthest Shore” and “Tehanu,” which serve as the culmination and epilogue of Sparrowhawk’s story. Peter Jackson might as well have been content with adapting “The Return of the King.” Like, “this is exactly the book of ‘The Lord of the Rings’ where the story of the Fellowship of the Ring comes to an end. And the creation of the Fellowship and the heroes’ journey to Mordor can be briefly told not even in flashbacks, but in dialogues.”

By the way, it would still be a better film than “Tales from Earthsea.” Because, at least, it would have a sea of special effects and grandiose battles. “Tales” has neither. It is a slow, mostly conversational film, and to understand its dialogues, you need to know the book cycle well. For example, the film does not even explain that in the world of Earthsea, all people have “true names” kept secret and nicknames known to others. This is critical to the plot, but it is not clear from the film – an obvious, childish mistake by an inexperienced author.

Furthermore, the film regularly hints at the events of the first two books instead of showing them, significantly simplifies the original narrative, and tries to promote Prince Arren to the main characters and push Sparrowhawk aside. Naturally, the plot resists this (if Cob is Sparrowhawk’s old adversary, then the Archmage, not the teenage prince, must confront him), the film insists… And as a result, the classic fantasy saga turns into something drawn-out, barely intelligible, very primitive, and irritating to both Le Guin fans and those who expect sweeping magical battles from a fantasy cartoon. The final slap in the face to viewers is the “deus ex machina” ending (in this case, a “dragon ex machina”). This is, admittedly, a direct quote from “Tehanu,” but in the context of the book, the corresponding scene is better justified.

“Tales from Earthsea” fails even the simplest task – to offer viewers a charming protagonist to empathize with. Sparrowhawk remains too mysterious to the public throughout the film (he is not mysterious to readers of the novels, but we are now discussing the adaptation), and Arren is presented as an obsessed psychopath who begins the film by killing his father, an obviously outstanding ruler. In Le Guin’s books, by the way, there is nothing like this, and the film does not really explain what made the young man commit this atrocity. Are you ready to empathize with such a hero? Yes, he behaves more decently later on, and he sincerely regrets his crime, but still… Patricide is too grave a sin to commit without a good reason and hope for human sympathy.

Technical Aspects

What about the graphics and animation, traditionally the strengths of Ghibli films? They are decent in “Tales from Earthsea,” but no more than that. Not comparable to “Howl’s Moving Castle” or “Spirited Away.” The professionalism of the artists is felt in the film, but not the inspiration. It turns out that it takes more than just bearing the Miyazaki name to create an animated masterpiece. Who would have thought!