The End of a Legend

It’s a common belief that Americans are only interested in themselves, viewing Europe as a mysterious, impenetrable forest and Asia as a vast, untamed wilderness.

Another widespread notion is that an Oscar win guarantees distribution success. This, too, is a myth. Some Oscar favorites might flicker on a few screens and garner some press, but that hardly constitutes a successful release.

The idea that Americans lack curiosity conveniently explained our failures in international markets – it was their fault, not ours. In recent years, a new justification has emerged: interest in Russia has waned, replaced by animosity, leading to neglect of our cinema.

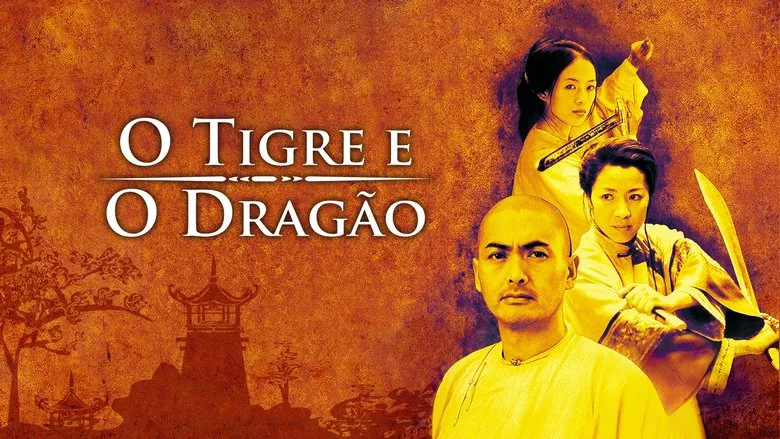

However, the success of the Taiwanese film “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” challenges this claim. Taiwan is hardly a country that has ever captivated America. Many Americans likely couldn’t even locate it on a map. Yet, they flocked to theaters to see the film. The comforting legends about the film’s Hollywood origins are nothing more than cinematic alchemy. It’s no more American than “Moloch” is German. In fact, it’s even less so: “Moloch” is spoken in German, while “Crouching Tiger” is in Mandarin, forcing American audiences to grapple with subtitles.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Similarly, the Italian tragicomedy “Life is Beautiful” achieved tremendous success. Yet, the average American is more familiar with pizza than with Italian film stars. Both cases demonstrate that external factors, such as political enlightenment or Russian oil prospects, cannot draw audiences to the cinema. Only the films themselves can – the complex blend of ideas, worldviews, images, and talent that resonates with viewers.

The Treacherous Turncoat

The word “resonates” is key here, despite its seemingly frivolous aesthetic connotation. We instinctively distance ourselves from unpleasant individuals, and the same holds true for films created by them. I want to emphasize that I am solely focused on this aspect, not the multifaceted nature of cinema as an art form, the evolution of cinematic language, or other intricate nuances of arthouse cinema. I am interested in the nature of cinema as a means of communication between people and cultures, and why this channel is chronically clogged with films that are unwanted not only in the distant United States but also in nearby Europe, and even in Russia itself.

The favorite argument of some filmmakers – their indifference to the audience – is a deceptive figure of speech. What kind of artist doesn’t need me, but only my money, so that they can make another film for their inner circle? Cinema is not a notebook where one can write a poem “for the drawer.” Cinema is an industry, and an industry cannot exist without consumers. Even a director indifferent to the audience requires significant funds for self-expression. The money comes either from the audience (which is normal) or from the taxpayer (which is not), but lovers of scattering audiences constantly forget about this circumstance.

Therefore, the viewer naturally forgets about such lovers. The distribution forgets – both domestic and global. Even an institution such as the American Film Academy, which is considered the most influential in the world of cinema and film success, forgets. Only films that people watch are quoted there. The rest are not.

All films that have managed to cross borders and go into wide release are made for viewers. Western critics appreciate this quality (“Life is Beautiful”, the Brazilian “Central Station”, the Taiwanese “Crouching Tiger”, etc. are enthusiastically accepted by them); ours, as a rule, grimaces. Now we are scolding Soderbergh for betraying “arthouse” with “the people”. Stupid.

“We’re Not From Around Here…”

Resonance equates to comfort. Audiences are accustomed to high-quality visuals and sound. Watery tones and flat, nasal dialogues, characteristic of our films, evoke a sense of sloppiness, archaism, and poverty. The majority of our films are substandard goods.

Worse, from the perspective of the modern politically correct world, our understanding of the very purpose of cinema is substandard. We are convinced that the public wants the truth, and we interpret this truth as a striptease, exposing only the unsightly. This began when perestroika lifted the ban on criticism, and “chernukha” (a genre of films depicting harsh and bleak realities) flooded the cinema. More often than not, there was no exposure of birthmarks here – “chernukha” had a clear commercial bias: criminal themes sold well in Russia, and the exoticism of wild customs sold even better in the West. A telling example is Vitaly Kanevsky, a very gifted director who amazed intellectuals with the unprecedented level of truth in the autobiographical film “Freeze, Die, Come to Life.” The film about a prison childhood received a prize in Cannes, and the director, who had suffered from the Soviets, realized that suffering was his capital. His subsequent films were opportunistic, but the outlandish texture carried him for a while, and the director left Russia in the hope of long-term success. The success turned out to be short-lived: watching the wildness of customs quickly became boring, and Kanevsky had no new ideas.

His fate is the fate of our cinema of the 90s. It sucked the meager well of “chernukha” and continues to suck, although the source has dried up. “Chernukha” was not a new level of truth – it was the stump of a train station beggar, shamelessly put on display. They give to such a beggar, but with disgust – they hurry to leave. And cinema must earn money, and with dignity – so that they hurry to come to it.

For those for whom the word dignity sounds too moralizing, I will say otherwise: a person with dignity is more pleasant than a person tearing his undershirt on his chest, and therefore his efforts are more commercially effective.

The Enigmatic East

Here lies the secret to the success of the new Chinese cinema, which seems to exist on another planet for Europe and America, yet conquers European and American screens. It has long overtaken us, although it has a less glorious history, and the Chinese mentality is even further from the American than the Russian. It can show life as horrific as it wants, but it always has human and national dignity. It tells about life, without complaining to the world about “unhappy China”, like our cinema - about “unhappy Russia”, a “God-forgotten” country; its heroes are worthy of love and sympathy. Our “Peculiarities of the National Hunt” frighten: each of the peculiarities goes against generally accepted values. We flaunt what is usually ashamed of. “They” and “we” diverged fundamentally.

They tell – we whine, they cultivate the positive – we cherish criminal consciousness, indulge complexes and provoke aggression, they are patriots – we do not believe in ourselves or in our own country; for them, political correctness is indisputable – for us it is an excuse to snarl, and the basic concepts of “morality” and “spirituality” are out of fashion for us, like bras. These are the barriers that separate us more reliably than state borders. As director Boris Ayrapetyan noted at the plenum of cinematographers of Russia, our cinema is now a destructive, not a creative force.

But who wants to deal with convinced destroyers? What madman finds it so pleasant that he will pay money for it?

Kirdyk Means Harakiri

Self-deprecation was supposed to be replaced by an antithesis. In the best case, “The Barber of Siberia” arose, in the worst - “Brother-2”. Both films are primarily ideological. “The Barber” should arouse longing for “Russia that we have lost” and turn minds towards a sweet monarchy. “Brother-2” commercially exploited the xenophobia wandering in the “ochlos” and made it the banner of the crowd. Both options, with all their skill, cause natural dislike of the unengaged viewer. I’m not even talking about the authors’ orientation towards the West, which they themselves reject: Mikhalkov makes a film half in English, Balabanov makes a poor version of an American action movie. Both films want to take “national identity”, but in fact they are cosmopolitan and do not express Russia as “Life is Beautiful” expresses Italy.

Take a look at the “Oscar” and rating lists - who is in demand? Gladiator, a model of nobility; Erin Brockovich, a fighter for justice; Billy Elliot, stubbornly going to his dream, a new Maresyev Tom Hanks in “Outcast”, an exposer of health-damaging machinations at a tobacco company from the film “The Insider”, new Romeo and Juliet in “Titanic”… Heroes are strong, with ideals, you want to deal with them. In our cinema, an attractive hero cannot be found, and even erotica is nauseating. You have to admire either the unearthly junker Tolstoy, who faints at the sight of a woman, or the semi-fascist Danila Bagrov.

“Arthouse” is a special case. It does not count on a large audience and is aimed at the future of cinema, forming new ideas and a new language. But even the future, according to our arthouse, is also dark and terrible. With outstanding merits at times, its samples represent the same tendency of hopelessly combing wounds, express a society that has stopped forever (which is half-truth) and masochism as a “peculiarity of the national character”. This is a well-made, but still a “stump”.

Black and White Cinema

It is foolish to question the importance of arthouse for art and it does not need protection. But it is already certain that the categories that are basic for mass cinema need protection. I have already said about some. It is necessary to add the malicious word “myth”. There are critics who swear by this word. They should be pitied, as they pity a color-blind person: mythological consciousness in the modern understanding is available only to a person who is able to independently separate the ideal from harsh reality and not confuse operetta with social film drama, measuring everything with one yardstick. Of course, you can hang signs for the incomprehensible: this is a lion, not a dog, but if you focus on color-blind people, the cinema will have to become black and white.

International success accompanies films where, with any exotic texture, there is a common language of ideals. Previously, our cinema was separated from the world by a wall of communist norms, but there remained points of mutual understanding in the best, world-recognized paintings. Now the time has come for rapprochement, and we are like without pants: we have neither ideals, nor norms, nothing at all. And there are no norms without them - they are dictated by a sense of self-preservation: declarations, commandments, laws written and unwritten arise, and everything else that we confuse with the restriction of freedoms and that is actually a sign of civilization. Art is a free tree, but it is possible to attribute divine origin to it only in the same myth. A product of human consciousness, it is subject to all its diseases, including a tendency to suicide. You can admire the freely growing jungle of the Amazon, but no one will live there - they will prefer a park area not clogged with thistles. The alternative to human norms is lawlessness. The ship of society can be rocked as much as you like, but art is its gyroscope. Without a clear sense of top and bottom, the ship will turn over. And everyone around will only be surprised: well, suckers!