The End of a Legend

It’s a common belief that Americans are only interested in themselves, viewing Europe as a mysterious, impenetrable forest and Asia as a vast, untamed wilderness.

Another prevailing myth is that an Oscar win guarantees distribution. However, some Oscar favorites might only grace a handful of screens, generating some buzz but hardly constituting a wide release.

The notion of uninterested Americans conveniently explained our failures in foreign markets – it was their fault, not ours. In recent years, a new excuse has emerged: waning interest in Russia coupled with growing animosity, leading to neglect of our cinema.

Challenging Preconceptions

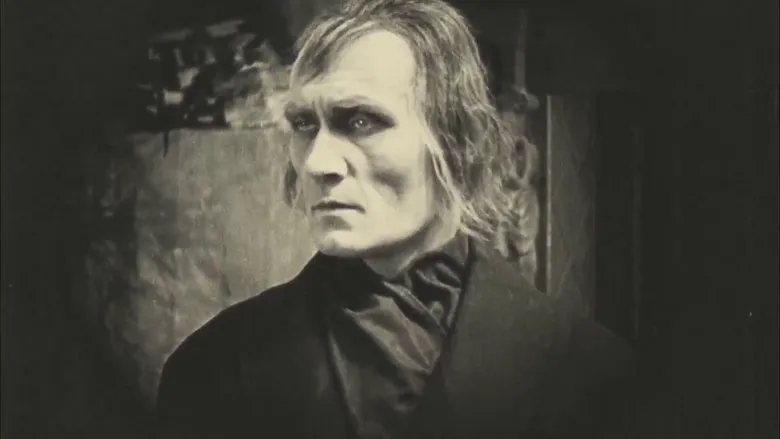

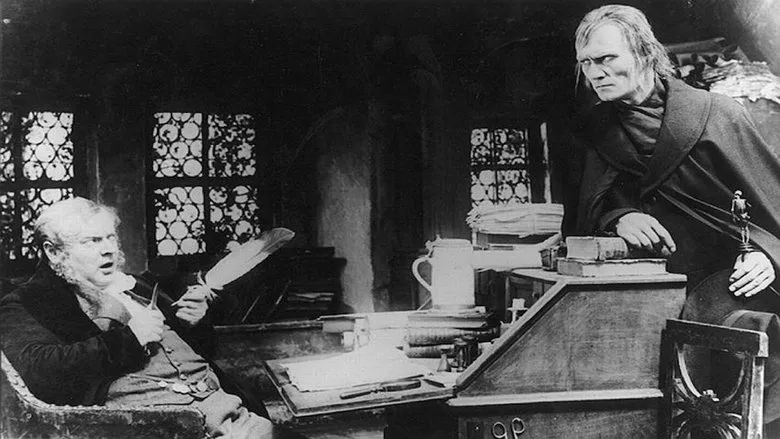

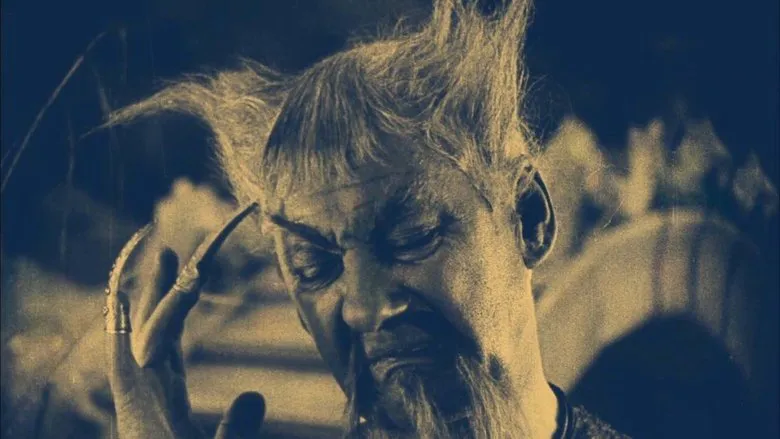

The success of the Taiwanese film “Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon” challenges this narrative. Taiwan is hardly a country that has ever captivated American interest, and many Americans likely couldn’t even pinpoint it on a map. Yet, they flocked to theaters to see it. The comforting legends about the film’s Hollywood origins are mere cinematic alchemy; it’s no more American than “Moloch” is German. In fact, it’s even less so: “Moloch” is spoken in German, while “Crouching Tiger” is in Mandarin, forcing American audiences to grapple with subtitles.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Similarly, the Italian tragicomedy “Life is Beautiful” achieved tremendous success, despite the average American being more familiar with pizza than Italian film stars. These examples demonstrate that external factors like political enlightenment or Russian oil prospects don’t drive audiences to the cinema. Instead, it’s the films themselves – the complex blend of ideas, worldviews, imagery, and talent – that resonate.

The Importance of “Pleasant”

The word “pleasant,” despite its seemingly frivolous aesthetic connotation, is key. We instinctively distance ourselves from unpleasant people, and the same holds true for films made by them. I’m focusing solely on this aspect, not the multifaceted nature of cinema as art, the evolution of cinematic language, or other arthouse intricacies. I’m interested in the nature of cinema as a means of communication between people and cultures, and why this channel is chronically clogged with films that fail to resonate, not only in the distant US but also in nearby Europe, and even in Russia itself.

The common refrain among certain filmmakers that they are indifferent to the audience is a deceptive figure of speech. What kind of artist doesn’t need me, but only wants my money to make another movie for their inner circle? Cinema isn’t a notebook for scribbling poems “for the drawer.” It’s an industry, and industries require consumers. Even a director indifferent to the audience needs significant funding for self-expression, which comes either from the audience (the ideal scenario) or the taxpayer (problematic), a detail often overlooked by those who dismiss the importance of viewers.

Consequently, the audience forgets about these filmmakers, as does distribution, both domestic and international. Even institutions like the Academy Awards, considered the most influential in the film world, only recognize films that people actually watch.

All films that successfully cross borders and achieve wide release are made for audiences. Western critics appreciate this quality (as seen in their enthusiastic reception of “Life is Beautiful,” the Brazilian film “Central Station,” and “Crouching Tiger”), while our critics often scoff. We now criticize Steven Soderbergh for betraying “arthouse” for “the masses,” which is foolish.

“We’re Not From Around Here…”

Pleasant means comfortable. Audiences are accustomed to high-quality visuals and sound. The washed-out colors and flat, nasal dialogues characteristic of our films create a sense of sloppiness, archaism, and poverty. Much of our cinema is substandard.

Worse, our understanding of cinema’s purpose is out of sync with the modern, politically correct world. We believe the audience wants truth, which we interpret as a striptease, exposing only the unsightly. This began when Perestroika lifted the ban on criticism, and “chernukha” (grim, bleak films) flooded the screens. Often, there was no genuine exposure of societal ills, but rather a clear commercial motive: crime sold well in Russia, and the exoticism of savage customs sold even better in the West. A prime example is Vitaly Kanevsky, a highly talented director who stunned intellectuals with the unprecedented level of truth in his autobiographical film “Freeze Die Come to Life.” The film about a prison childhood won an award at Cannes, and the director, who had suffered under the Soviets, realized that suffering was his capital. His subsequent films were opportunistic, but the bizarre subject matter carried him for a while, and he left Russia expecting long-term success. However, the success was short-lived: audiences quickly tired of the savage customs, and Kanevsky had no new ideas.

His fate mirrors that of Russian cinema in the 1990s. It drained the meager well of “chernukha” and continues to do so, even though the source has dried up. “Chernukha” wasn’t a new level of truth; it was the stump of a train station beggar, shamelessly displayed. Such a beggar might receive alms, but with disgust, and people hurry away. Cinema, on the other hand, should earn money with dignity, so that people rush to see it.

For those who find the word “dignity” too moralistic, I’ll put it differently: a person with dignity is more pleasant than someone tearing open their shirt, and therefore their efforts are more commercially effective.

The Enigmatic East

This is the secret to the success of new Chinese cinema, which seems to exist on another planet for Europe and America, yet conquers European and American screens. It has long surpassed us, despite having a less illustrious history, and the Chinese mentality is even further removed from the American one than the Russian. It can depict life as horrific as it wants, but it always contains human and national dignity. It tells stories about life without complaining to the world about “unhappy China,” as our cinema does about “unhappy Russia,” a “God-forsaken” country. Its characters are worthy of love and sympathy. Our “Peculiarities of the National Hunt,” on the other hand, are frightening: each peculiarity goes against generally accepted values. We boast about what should be a source of shame. “They” and “we” have diverged fundamentally.

They tell stories – we whine; they cultivate positivity – we nurture criminal consciousness, indulge complexes, and provoke aggression; they are patriots – we believe in neither ourselves nor our country. For them, political correctness is unquestionable; for us, it’s an excuse to sneer. Basic concepts like “morality” and “spirituality” have gone out of fashion like bras. These are the barriers that separate us more effectively than state borders. As director Boris Ayrapetyan noted at a plenum of Russian filmmakers, our cinema is now a destructive force, not a creative one.

But who wants to deal with committed destroyers? What madman finds it so pleasant that they’ll pay for it?

Kirdyk Means Harakiri

Self-deprecation should have been replaced by its antithesis. At best, we got “The Barber of Siberia”; at worst, “Brother 2.” Both films are primarily ideological. “The Barber” is meant to evoke nostalgia for “the Russia we lost” and turn minds toward a benevolent monarchy. “Brother 2” commercially exploited the xenophobia simmering in the “ochlos” (rabble) and made it a banner for the crowd. Both options, despite their craftsmanship, evoke natural antipathy in the unengaged viewer. I’m not even talking about the authors’ orientation toward the West they reject: Mikhalkov makes a film half in English, Balabanov creates a poor version of an American action movie. Both films want to capitalize on “national identity,” but in reality, they are cosmopolitan and don’t express Russia the way “Life is Beautiful” expresses Italy.

Look at the Oscar and ratings lists – who is in demand? Gladiator, an example of nobility; Erin Brockovich, a fighter for justice; Billy Elliot, stubbornly pursuing his dream; the new Maresyev, Tom Hanks, in “Cast Away”; the whistleblower exposing health-damaging machinations at a tobacco company in “The Insider”; the new Romeo and Juliet in “Titanic”… Strong heroes with ideals, with whom you want to associate. In our cinema, you can’t find an attractive hero, and even the eroticism is sickening. We are supposed to admire either the unearthly Junker Tolstoy, who faints at the sight of a woman, or the semi-fascist Danila Bagrov.

“Arthouse” is a special case. It doesn’t count on a large audience and is aimed at the future of cinema, forming new ideas and a new language. But even the future, according to our arthouse, is also dark and terrible. Despite its sometimes outstanding merits, its examples represent the same tendency of hopelessly picking at wounds, expressing a forever-stopped society (which is half-true) and masochism as a “peculiarity of the national character.” This is a well-crafted, but still a “stump.”

Black and White Cinema

It is foolish to question the importance of arthouse for art, and it does not need protection. But it is already certain that the categories that are basic for mass cinema need protection. I have already said about some. It is necessary to add the malicious word “myth”. There are critics who swear by this word. They should be pitied, like a color-blind person: mythological consciousness in the modern understanding is available only to a person who is able to independently separate the ideal from harsh reality and not confuse operetta with social film drama, measuring everything with one yardstick. Of course, you can hang signs for the incomprehensible: this is a lion, not a dog, but if you focus on the color-blind, the cinema will have to become black and white.

International success accompanies films where, with any exoticism of texture, there is a common language of ideals. Previously, our cinema was separated from the world by a wall of communist norms, but there remained points of mutual understanding in the best, world-recognized films. Now the time for rapprochement has come, and we are like without pants: we have neither ideals, nor norms, nothing at all. And there are no norms without them - they are dictated by a sense of self-preservation: declarations, commandments, laws, written and unwritten, and everything else that we confuse with limiting freedoms and that is actually a sign of civilization arise. Art is a free tree, but attributing divine origin to it is possible only in the same myth. A product of human consciousness, it is subject to all its diseases, including a tendency to suicide. You can admire the freely growing jungles of the Amazon, but no one will live there - they will prefer a park area not clogged with thistles. The alternative to human norms is lawlessness. The ship of society can be rocked as much as you like, but art is its gyroscope. Without a clear sense of top and bottom, the ship will turn over. And everyone around will only be surprised: well, suckers!