Bond is Present, But the Thrill is Gone: A Review of “Die Another Day”

Going to see “Die Another Day” isn’t forbidden, much like humming, “Steady, comrades, all to your places… Our proud ‘Varyag’ does not surrender to the enemy,” simply because the tune matches the rhythm of your steps to the subway, overtaking other pedestrians. The Bond franchise truly surpasses everyone in its deep roots in film history and mass consciousness, as well as its contextuality – every jab at it lands on an expensive advertising billboard (“Aston Martin,” “Martini,” Moneypenny, “Bond. James Bond,” Nokia phones, Philips shavers, the ban on the name “Goldmember” as if it relates to “Goldfinger,” and heaven forbid Bond picks up a book – let it not be by B. Akunin).

Everything related to the pleasant-looking savior of humanity, for whom everything that moves is an excuse to either shoot or sleep with, and who wears a tuxedo and bow tie as comfortably as he wears his underwear, is so familiar and beloved that after forty years and for the twentieth time, you still rush to see him. He’ll please you with something, or if not, at least he’ll be present.

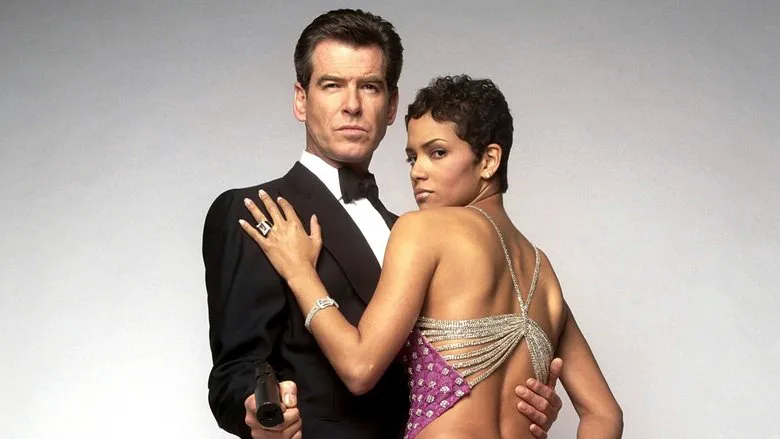

However, Lee Tamahori’s “Die Another Day” truly doesn’t please with anything. The highly advertised Halle Berry is vulgar to the extreme – reminiscent of Musya Vinogradova from the domestic film “From the Life of Vacationers,” whom she closely resembles. But Musya Vinogradova specifically satirically portrayed a flirtatious, aging coquette on the winter Sochi embankment. Halle Berry on the Varadero embankment is supposedly young, but she shoots her eyes in the same way, despite her figure not resembling Ursula Andress, whom she emulates by emerging from the waves, as in the first Bond film. Provisionally, one can note two things in the entire hour and a half: when in the first scene, Bond the surfer and his assistants perform figure skating on a tsunami, which in itself is a good idea (figure skating on skis from early Bond films eventually became an Olympic sport), and the enemy’s face, encrusted with jewels in an oriental style (with the current fashion for piercing, we can now expect a surge in diamonds). Nothing else amazes the imagination.

Admittedly, the anniversary Bond film isn’t made to amaze the imagination but rather as a sign of respect. Its mandatory program is a roll call with each of the previous nineteen films, even if only in the form of a hint. It’s no coincidence that Halle Berry emerges from the waves in the old way, just as it’s no coincidence that the main villain descends on Piccadilly on a parachute with a British flag design. This is also in the old style, and the duel with the main villain in the gym has also been done before, only the sport has changed: in “Die Another Day,” they fence; in “Goldfinger,” it was croquet. But what’s joyful about such a digest if the full text has long been known? Moreover, on the basis of the supposedly old nineteen “full texts,” truly new variations have long been emerging outside the Bond franchise – from “Men in Black” to “XXX” plus all the film adaptations of computer games. In them, with the same standards (sex-gold-gun), there are already more effects, and the sharpness hasn’t become tiresome yet. Therefore, this time, whether you want to or not, you have to comprehend precisely and only the joy from the very fact of the anniversary Bond’s presence.

British conservatism is rich enough in this. “Die Another Day” is not a film about Agent 007 but about Pierce Brosnan playing the role of this agent. Brosnan has long been known as “not an eagle” – a good guy, but his chin isn’t square. In life, he has older children from his first deceased wife, infants from a young girlfriend, a house, a household, he’s approaching fifty, and now he’s again “summoned” to portray armored battles in the forests of North Korea. Thank goodness, he doesn’t have to jump anywhere – the computer will paste you into any fight on the bumper of a speeding amphibian – but he still has to go. He doesn’t want to immensely. When Bond in a youth jacket communicates with Koreans, when he later sticks out from the crowd of London journalists in a business suit, when he supposedly cheerfully joins the ranks of the Icelandic elite under the mask of “social life,” Brosnan himself is clearly uncomfortable. His eyes are strained, his phrases are demonstrative, and he doesn’t want to communicate. He doesn’t want to see these people, let alone save them from another maniac.

“I’m tired!!!” – his entire psychophysics screams. – “Don’t overdo it!!!”. However, they overdo it, and the most difficult thing is communicating with colleagues and lovers who are asking for “closeness.” Oh, it’s in vain that for the first time in the Bond franchise, he was allowed to have sex right on camera. With both “Jinx” and “Miranda Frost,” Brosnan portrays the required body movements, as if constantly asking himself: “Lord, what am I doing in this bed? Where to put my shoulders, where to put my hands? I have children, a family”… Similarly, in all the ridiculous spacesuits and tuxedos, chases and duels, his only task is to work with minimal costs. He needs to run after the plane – so be it, I’ll run; he needs to carry this dead cow in his arms – well, let’s say I’ll carry it, but with no extra effort, not a single kind word, nothing personal. Two moments in the entire film when Bond is adequate are in the Korean prison and on the Cuban coast. In prison, he sits overgrown, alone, and no one bothers him for six months, and in Havana, he wanders alone in a Hawaiian shirt for at least some time, and that’s good. Warm, free, curious.

At first, “Die Another Day” was still hiding something – Korea, Hong Kong, Cuba, and England quickly replaced each other – but with large-scale Iceland, complete self-exposure begins. Here, one can only see and understand that Brosnan is a very closed-off, shy, slightly slow-moving aging man, prone to comfort and peace, a lazy sybarite who has long parted with illusions. Alone, nothing can be done for a long time, not even work, let alone win. You can only be alone at home, behind a three-meter fence with barbed wire, and the entire plot of the anniversary Bond film boils down to one specific exhale: “I want to go home.” This is a plot about an artist who will not resist the enemy-producers who have dragged him into another hateful adventure; he will not resist anything because he has in mind his own benefit, quite commensurate with the troubles. He will even sign up for the Bond franchise further, because fame and money, of course, will pay off the need to constantly restrain the attacks of growing hatred for the “outside world.” But as you sit on an artist, so you get off; he will nod, but he will do everything his own way; he is secretive and does not intend to share anything with anyone, and then he will still come home and stretch his long legs towards his slippers. Once, “Magnificent” showed this plot as a joke; Brosnan realized it in reality.