Deconstructing “Dogville”: Beyond the Screen

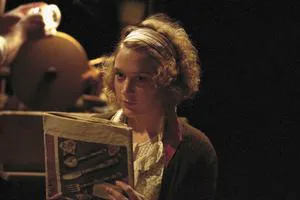

Discussing “Dogville” before its release was akin to saying nothing at all. Its meaning unfolds progressively, and the true reward lies in individual interpretation. Now that “Dogville” has left the theaters, the plot is no longer a secret, allowing for discussion among those who have experienced it. Moreover, there’s been ample talk about von Trier, particularly regarding Kidman’s character.

Is she a sent angel, acting flawlessly, rendering “Dogville” irrelevant to humans, as we are not angels? Or is she a temptress, a devil, making Trier a provocateur, ultimately a fascist? Some sophisticated viewers dismiss Kidman’s acting entirely, seeking refuge in any aesthetic interpretation to avoid confronting the questions of “who is to blame” and “what to do” with Dogville. However, Trier himself cautioned that Kidman’s character is “by no means a heroine. She is an ordinary person – with good intentions, but still an ordinary person.” Indeed, she remained consistent throughout, stating, “I had one close person in the world – my father, but the gangsters took him away.” Her behavior upheld noble relationships. But what about the questionable ending, and how did it come about? Before the moon rose, Kidman still hoped to find good in everyone, believing all Dogville residents were kind, just weak. When the cold moonlight revealed things unequivocally, without ambiguous shades, she suddenly decided to “drown them all.” She succumbed to emotion, proving she is not an angel. Furthermore, mass murder, especially by proxy, is never justified, it’s not up for debate, and it’s not a solution, regardless of how justified it might seem to put a gun to Tom’s head. On the other hand, to consider an unwilling victim, who didn’t rebel against her conscious tormentors until the very end, a temptress or devil is pure demagoguery. The issue isn’t about her, the victim, as Trier argues.

The massacre, like the entire film, is not literal but conceptual. No one actually shot anyone, just as there was no real dog. The massacre appears as a thought of inevitable retribution only because it concludes the film. In reality, the film simply found the ideal form for something else: discerning baseness. Literary classics have grappled with this question for two thousand years, with Ivan and Alyosha Karamazov debating the tear of a child. Incidentally, the angel Alyosha also cried out, “Kill the scoundrel, kill the scoundrel.” For two millennia, Sophocles and Shakespeare, Goethe and Schiller, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky achieved powerful breakthroughs in classifying baseness, but these were merely side effects. They also had genuinely strong personalities, various Antigones and Nikolai Stavrogins with their own problems. Was it purely about baseness? Von Trier’s approach differs in this current state of complete immoralism with moral relativism. It’s either “everyone has their own truth” or “I don’t care.” He tackles these seemingly irrefutable truths, examines them closely, and suddenly everything is reversed. Regardless of how the audience perceives the events in “Dogville,” one thing remains undeniable: baseness is visible, and very clearly so. So clear that the entire film can be viewed as a catalog of it.

For example:

- If someone loses at checkers their whole life but continues to play, sooner or later they will invent a gas chamber.

- If someone rang the bell to save a person because they were told to, they will ring it when told to again, even if the bell is now that person’s head.

- If someone hits you first for the sake of their children, it means they hate their children.

- If someone held onto the doorknob behind which you were being raped but didn’t enter, they will later inform on you to the murderers.

- If someone takes money upfront, they will never keep their promise.

And so on – for three hours, the classification of baseness reaches the most subtle nuances, comparable in their universality to the Christian commandments. Baseness is visible because, after two thousand years of Christian culture, “Dogville” has finally achieved a tabular and graphical form of depiction. The fact that the film is a graph, a classification, is indicated not only by the “black velvet” backdrop, the purely literary, “narrative,” “standard” voice-over, or the division into equally literary “chapters.” Not only by the abundance of world-class stars, where the personal expressiveness of Lauren Bacall and Ben Gazzara, etc., only emphasizes the predictability – the complete predictability of the characters, their presence in “Dogville” as a dotted line, not as people. But essentially, the entire plot is also a table, a pure standard of the tragic genre. Once, Medea, forcibly taken from Colchis by Jason, was driven to the point where she killed her children (according to some accounts, she didn’t kill them but was slandered to justify her execution). The recent English film “The Revenger’s Tragedy” didn’t fit into a tabular form only because it took the same plot of driving a person to extremes from Webster’s tragedy, written in the 17th century. There were more frills in the 17th century than in 1930.

Von Trier’s recent “Dancer in the Dark” was similarly distinguished by the “frills” of a musical. The essence of “Dogville” is much clearer in comparison. The problem is not in the execution of the innocent or the shooting of the guilty, not in the responsibility for one’s words, but only in recognizing the difference between words and their absence. Even if “no one is innocent,” everyone without exception has a concept of innocence. Of course, for most, it comes from an elementary idea of their own innocence, followed by a constant substitution of life with self-justification, at any cost, including the lives of others, even everyone, why be petty. But ultimately, it doesn’t matter how the idea of difference is formed, what matters to von Trier is that it is common, universal at the level of a simple graph in the film and a conditional instinct in you. It then allows you to judge what is baseness, not only from your own perspective but objectively and accurately in each specific case. “Dogville” has made this difference a real fact, almost music – exactly to the extent that the audience is indifferent to the film. It doesn’t pretend to be more.

The film is set in 1930 for a reason, embodying practically a single moment in life. Time there is purely psychological, meaning it doesn’t actually flow. In a life where time constantly flows to an unknown destination, baseness is much more mobile and invisible to the naked eye in a large crowd. Truly widespread and currently active, baseness is elusive, like fleas on a cat – all two thousand years haven’t been idle either. Trier wouldn’t have enough life to express such elusiveness in a tabular form.