Deconstructing “Dogville”: Beyond Good and Evil

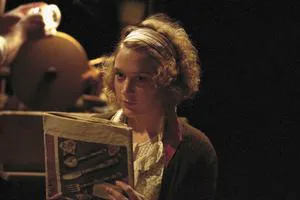

Before its release, discussing “Dogville” was akin to saying nothing at all. The film’s meaning unfolds progressively, and the true reward lies in individual interpretation. Now that “Dogville” has left the screens, the plot is no longer a secret, allowing for discussion among those who have experienced it. Much has been said about Lars von Trier in the past month, particularly regarding Nicole Kidman’s character.

Is she a sent angel, acting virtuously, rendering “Dogville” irrelevant to flawed humans? Or is she a temptress, a devil, making Trier a mere provocateur, or worse, a fascist? Some critics dismiss Kidman’s acting entirely, seeking refuge in aesthetic interpretations to avoid confronting the question of blame and the appropriate response to Dogville. However, Trier himself cautioned that Kidman’s character is “not a heroine. She is an ordinary person – with good intentions, but still an ordinary person.” Indeed, she remains consistent throughout, stating, “I had one close person in the world – my father, but the gangsters took him away.” Her actions consistently uphold noble ideals. But what about the ambiguous ending? Before the moon rises, Kidman’s character still believes in the inherent goodness of everyone, viewing the Dogville residents as kind but weak. When the cold moonlight reveals a stark reality, she abruptly decides to “drown them all.” This impulsive decision suggests she is not an angel. Furthermore, mass murder, even through intermediaries, is never justified. It’s not a solution, regardless of how righteous it might seem to personally execute Tom. Conversely, labeling a reluctant victim who never rebelled against her conscious tormentors as a seductress is pure demagoguery. The issue, as Trier suggests, lies not with the victim.

The Nature of Evil in “Dogville”

The massacre, like the entire film, is not literal but conceptual. No one was actually shot, just as there was no real dog. The massacre appears as a vision of inevitable retribution only because it concludes the film. In reality, the film finds an ideal form to explore something else: the discernment of baseness. Literary classics have grappled with this question for two millennia, exemplified by Ivan and Alyosha Karamazov’s debate over a child’s tear. Even the angelic Alyosha cried out, “Kill the scoundrel, kill the scoundrel.” For two thousand years, Sophocles and Shakespeare, Goethe and Schiller, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky achieved profound breakthroughs in classifying baseness, but these were often secondary to their exploration of strong personalities like Antigone or Nikolai Stavrogin and their individual struggles. Von Trier’s approach is different, reflecting a state of complete immoralism and moral relativism. In a world where “everyone has their own truth” or “nothing matters,” he examines these seemingly irrefutable truths, only to reveal the opposite. Regardless of one’s reaction to the events in “Dogville,” one thing remains clear: baseness is visible, and vividly so. The entire film can be viewed as a catalog of it.

For example:

- If someone consistently loses at checkers but continues to play, they will eventually invent the gas chamber.

- If someone rang the bell to save a person because they were told to, they will ring it again when instructed, even if the bell is now that person’s head.

- If someone strikes you first for the sake of their children, they hate their children.

- If someone held the doorknob while you were being raped but never entered, they will be the one to betray you to the murderers.

- If someone takes money upfront, they will never keep their promise.

“Dogville” as a Catalog of Baseness

And so on – for three hours, the classification of baseness reaches the subtlest nuances, yet remains universally relatable, akin to Christian commandments. Baseness is visible because, after two thousand years of Christian culture, “Dogville” finally achieves a tabular and graphical representation of it. The film’s graphical, classificatory nature is evident not only in the “black velvet” backdrop, the purely literary, “narrative,” “standard” voice-over, or the division into equally literary “chapters.” It’s also evident in the abundance of world-class stars, where the personal expressiveness of Lauren Bacall, Ben Gazzara, and others only emphasizes the predictability – the complete predictability – of the characters, their presence in “Dogville” as dotted lines rather than real people. Essentially, the entire plot is a table, a pure standard of the tragic genre. Medea, forcibly taken from Colchis by Jason, was also driven to the point of killing her children (though some claim she was framed to justify her execution). The recent English film “The Revenger’s Tragedy” failed to fit into a tabular form only because it borrowed the same plot of driving a person to extremes from Webster’s 17th-century tragedy. The 17th century had more frills than the 1930s.

The Enduring Relevance of “Dogville”

Von Trier’s recent “Dancer in the Dark” also featured such musical “frills.” The essence of “Dogville” is much clearer in comparison. The problem is not the execution of the innocent or the shooting of the guilty, nor is it the responsibility for one’s words, but simply the recognition of the difference between words and their absence. Even if “no one is innocent,” everyone has a concept of innocence. Of course, for most, this comes from a basic sense of their own innocence, leading to a constant substitution of life with self-justification at any cost, even the lives of others, or everyone, for that matter. But ultimately, how one’s understanding of the difference is formed is irrelevant. What matters to Von Trier is that it is shared, universally human, existing as a simple graph in the film and a conditional instinct within you. This allows us to judge what constitutes baseness, not just from our own perspective, but objectively and accurately in each specific case. “Dogville” makes this difference a tangible fact, almost musical – precisely to the extent that the audience is engaged with the film. It makes no greater claim.

The film is set in 1930 for a reason, capturing virtually a single moment in life. Time is purely psychological, meaning it doesn’t actually flow. In a life where time constantly flows to an unknown destination, baseness is much more mobile and invisible to the naked eye in a large crowd. Truly widespread and currently active, baseness is elusive, like fleas on a cat – it hasn’t been idle for two thousand years either. Trier would not have enough life to express such elusiveness in tabular form.