It Comes at Night: A Descent into Post-Apocalyptic Paranoia

In the realm of atmospheric psychological horror, It Comes at Night paints a chilling portrait of a post-apocalyptic world ravaged by a deadly plague. This is not your typical monster movie; it’s a slow-burn exploration of fear, paranoia, and the primal instincts that emerge when civilization crumbles.

A World Consumed by Fear

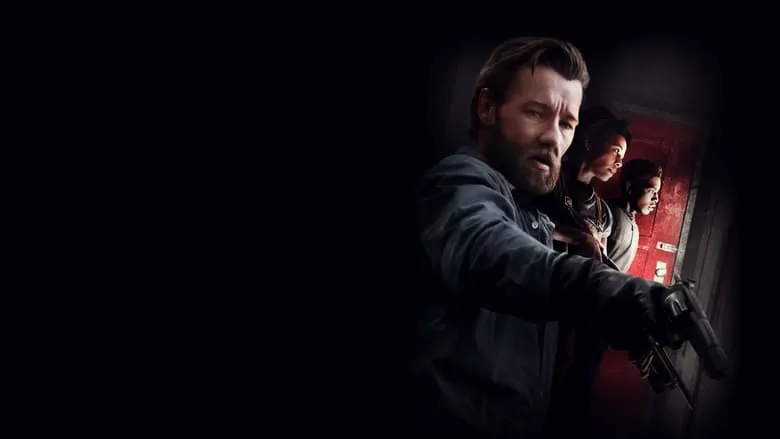

America is in the grip of a rapidly spreading plague, felling its victims within days. Civilization has collapsed, leaving survivors isolated and wary, haunted by the specter of disease and the threat of marauders. Paul (Joel Edgerton), his wife Sarah (Carmen Ejogo), and their teenage son Travis (Kelvin Harrison Jr.) have carved out a precarious existence in a remote cabin deep within the woods. They possess the essentials: food, water, weapons, and protective gear. Paul has established strict rules, the bedrock of their survival.

Distrust is Paul’s guiding principle, yet after agonizing deliberation, he makes the fateful decision to shelter Will (Christopher Abbott) and his family, desperate for refuge and offering livestock as recompense. However, the arrival of these newcomers only amplifies the paranoia that already gnaws at Paul’s soul.

The Primal Instinct for Survival

Our ancestors, as they roamed the African plains and spread across continents, did so in small family units. Other groups were perceived as threats, sometimes even as sustenance. While we’ve long abandoned the hunter-gatherer lifestyle, a deep-seated distrust of outsiders remains etched in our genes. This instinct surfaces with brutal force when societal structures collapse, and survival hinges on primal rules: “Your family must perish today so that mine may live to see tomorrow.”

A Director’s Vision of Terror

Trey Edward Shults, before embarking on his directorial career, honed his skills as an intern on Terrence Malick’s film sets. It Comes at Night marks the debut psychological horror film by this emerging American director. The characters are haunted by a very real external threat, where every venture outside, day or night, carries mortal danger. Yet, their fear of each other is just as potent as their fear of the plague. When resources are scarce, anyone can appear to be a “burden.” Especially when the survival of your own family hangs in the balance. Whether you’re inherently good or bad, your loved ones take precedence over strangers. And even prolonged cohabitation cannot alter this fundamental truth.

Building Atmosphere, Not Jump Scares

As a psychological horror film, It Comes at Night eschews cheap jump scares, opting instead to cultivate a relentlessly oppressive atmosphere of dread. Regardless of the characters’ actions, the music, set design, cinematography, and performances all underscore the imminent danger they face, swiftly infecting the audience with their paranoia. The film provides ample space for dark imaginings, making it difficult not to succumb to its game and speculate about when the external attack or internal discord will erupt. The night scenes are particularly unsettling, masterfully playing on humanity’s innate fear of the dark and the dense forest. However, even the daylight scenes offer no respite.

A Masterclass in Suspense

Shults’ film could be studied in directing courses as a prime example of building multifaceted terror with minimal resources. The film brilliantly provokes paranoia in scenes ranging from the burning of a corpse to a moment of lighthearted flirting. This, admittedly, is a rarity in horror films, which typically rely on a single trope, terrorizing the audience with a maniac or a ghost. In Shults’ film, fear permeates every crack and every word. Paradoxically, the only moments of emotional reprieve come during Travis’s nightmares, because they are, after all, unreal. Although, visually, these are the most disturbing segments of the film, so the “reprieve” is relative.

While the film boasts numerous strengths, it cannot be described as a profoundly deep or particularly original work. In recent years, we’ve witnessed a surge of post-apocalyptic horror films, and Shults’ film doesn’t deviate significantly from the established formula, nor does it offer anything that would elevate it to “unforgettable” status. However, within the confines of its style and genre, it is a powerful piece, and fans of on-screen horror should experience it in a cinema, where the atmosphere of nightmare is more readily palpable.