Jarhead: Echoes of a Familiar War

“All wars are different, all wars are the same” – this paradox concludes “Jarhead,” a new film based on the bestseller by Anthony Swofford, a veteran of the “Desert Storm” campaign. The latter half of the phrase resonates deeply, especially considering “Jarhead’s” release shortly after the triumphant success of the Russian film “The 9th Company” (2005). The similarities between the two films are so striking that one might think they were cut from the same cloth.

Striking Similarities in Narrative Structure

Sam Mendes’ “Jarhead” arrives as an echo of what we’ve already witnessed. Dramatically, they share a common structure. Neither film possesses a traditional plot with a clear chain of events. Instead, both are divided into three distinct “acts”: the grueling training of recruits, filled with humiliation and brutality; the actual military operations; and the bitter realization of the meaninglessness of heroism without a clear purpose or objective.

Both films present the war from the perspective of a participant, from their initial induction as raw recruits to their transformation into hardened soldiers, hysterically ready to sacrifice their lives for an unknown cause. The psychological pressure on the characters reaches extreme levels in both narratives, and even the infamous “wet pants” incident, which caused such a stir among female critics, is present in both “The 9th Company” and “Jarhead.” There’s also a touch of sentimentality, which particularly angered critics of “The 9th Company,” where the protagonist sits in a field of red poppies during a moment of silence. In “Jarhead,” he encounters a horse lost in the smoke, seeking protection but finding none. This scene is equally heartbreaking and, in my opinion, just as necessary.

Mendes’ Homage to Anti-War Classics

“Jarhead” was directed by Sam Mendes, known for “American Beauty” (1999). He created it as his response to similar anti-war films like Coppola’s “Apocalypse Now” (1979) and Cimino’s “The Deer Hunter” (1978), even including a helicopter attack scene from “Apocalypse Now” and subtly flashing the title of Cimino’s film on screen. We also compared “The 9th Company” to “The Deer Hunter.” The cinema of both countries persistently addresses the theme of the senseless slaughter that innocent young men, torn from their normal lives and driven to a state of savagery, must endure at the behest of politicians.

“The 9th Company” Triumphs

Given the unwritten rule in our criticism that anything domestic is inherently inferior to foreign, I have little doubt that “Jarhead” will be held up as an example for “The 9th Company” – a portrayal of unvarnished truth. However, this is one of the first times in years that our cinema clearly triumphs on the same playing field as the Americans. While the American film features only two characters with distinct personalities – the roles played by Jake Gyllenhaal and Peter Sarsgaard, surrounded by a largely faceless mass – the Russian film presents a full-blooded ensemble cast, with each character lingering in the memory. In the American film, the enemy is represented by ghostly figures in effective wide shots – appearing and disappearing for unknown reasons. In the Russian film, however, the “ghosts” materialize into characters, concisely but well-developed by the screenwriter and director. They reveal a crucial insight for the audience: these people of the desert have their own truth, which the rage-blinded protagonists never even consider.

However, the spectral nature of these figures in Mendes’ film is part of his theme. Americans traditionally aren’t interested in any “others” with their own truths and falsehoods – they focus on “their own guys.” The blurred figures of people with camels play the same role in the film as the windmills in “Don Quixote” – symbolizing a non-existent enemy, invented by a diseased imagination.

The Dehumanizing Training

The majority of the film’s two-plus-hour runtime is dedicated to the protagonist’s acclimatization to the new conditions of the barracks. The film is based on an autobiographical book that resembles a recruit’s diary. The recruit dreams of a career as a Marine – a hypersexual macho in a well-fitting uniform, ready for military and romantic exploits – a poster boy. Instead, he encounters mindless drills, humiliating rituals, dirt, sweat, and vomit, cleaning latrines, loneliness among his peers, thirst in the desert, and sexual deprivation. Gradually, a normal guy becomes a “tough bastard,” driven to a nervous breakdown and hysterically eager to shoot – regardless of who or why. This process forms the plot of the film. Military syndrome is its theme.

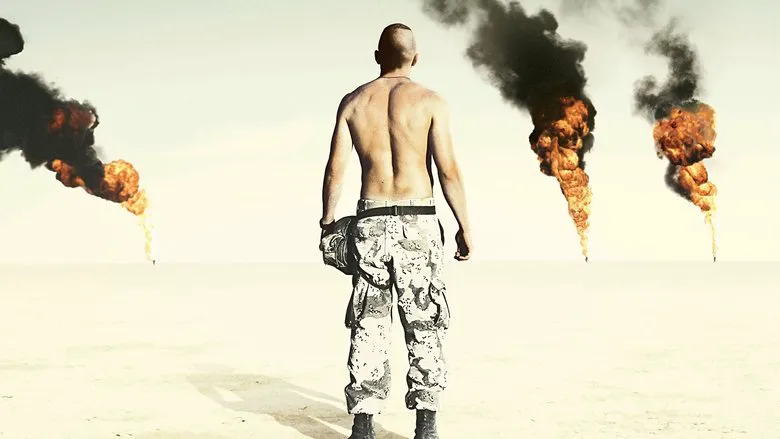

The Futility of War

All these superhuman overloads must have some kind of finale, and most importantly, some kind of meaning. But there is no enemy. American aviation bombs its own troops, the Marines stumble upon the rotting remains of some ancient battle, and the horizon flares with the torches of oil wells set ablaze by unseen Iraqis. The screen fills with crimson, and these almost monochrome shots of scorched and uninhabitable land are the most powerful impression of the film. The perception of the cosmic horror of these episodes is greatly diminished by the awareness that they were created mainly by computer and have little to do with the real images of the war in the Gulf. But this is a work of art, and we must get used to the fact that cinema is ceasing to be photographic and is increasingly turning to the computer, embodying the author’s fantasy, free from verisimilitude.

The ending is not strikingly original. The protagonist returns to ordinary life, but the visions of what he experienced will never leave him.

And the desperate realization that a person has accomplished the impossible, reached the breaking point, but never had the chance to fire a single shot, is equivalent to the realization that an entire life has been wasted.