Disaster movies have a magnetic pull on audiences, drawing them in with spectacles like “The Towering Inferno,” “Volcano,” “Jaws,” “Earthquake,” and “Titanic.” From a safe distance, viewers revel in the thrill of watching planes crash and ships sink, experiencing intense sensations while comfortably seated in air-conditioned theaters with popcorn. These films are primarily about spectacle and thrills. According to the unwritten rules of the genre, everything else serves as either exposition or a redemptive finale, while the core of the movie is a grand display of disaster.

However, some filmmakers successfully blend the spectacle with artistic elements, such as well-developed characters, talented actors, psychological depth, and even subtle explorations of serious issues. This was the case with the American “Titanic” and the Russian “Crew.” These films have greater longevity and are remembered fondly by future generations. The rest is just for show.

It’s often said that disaster movies frighten us, but that’s not entirely true. American disaster films typically follow an established formula: a strong protagonist (a brave firefighter, an experienced sailor, a police officer, or simply a courageous individual who finds themselves among the distressed and manages to unite them in a critical moment) invariably confronts the natural or technological catastrophe. Viewers leave the theater pleasantly stirred, confident that someone (a person, society, the government, the country) will come to their aid when needed.

This is where American cinema shows its constructive side, especially when compared to contemporary Russian films, which, in the name of a poorly understood realism, deprive viewers of any hope.

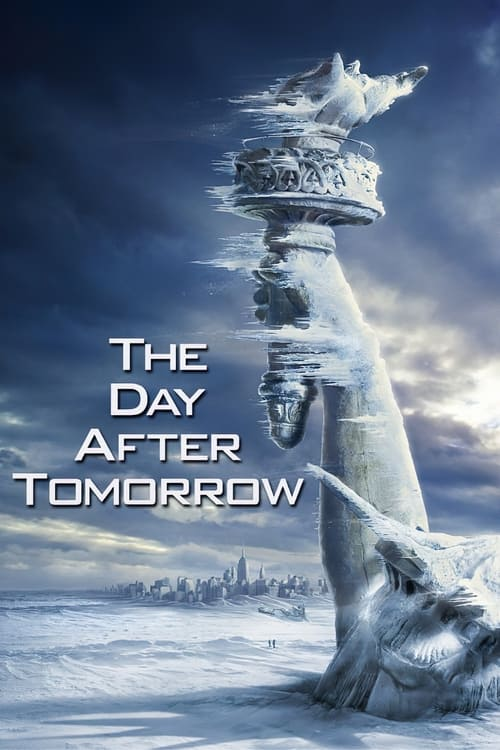

Roland Emmerich’s Vision

If Roland Emmerich had filmed “The Day After Tomorrow” at “Mosfilm” and destroyed St. Petersburg instead of New York, he would have been accused of hating everything Russian. However, he made the film in Hollywood, casually tearing down the famous “Hollywood” sign from the hills and gleefully ravaging two of the largest cities in the United States. Yet, no one reminded him that he was German or suspected him of hating everything American. This lack of suspicion distinguishes a self-assured society from one riddled with complexes.

Emmerich consistently dismantles America. He trampled it with the powerful paws of “Godzilla.” He unleashed aliens upon it in “Independence Day.” Now, learning from the success of these blockbusters, he plunges it into the depths of a more realistic disaster: global warming, melting glaciers, and, as a result, flooding and a new ice age that instantly engulfs the entire Northern Hemisphere. He shows no interest in the fate of his native Germany or, say, Siberia, where one of the epicenters of the global catastrophe is located. But it would be foolish to accuse him of negligence. He’s making a film whose purpose is to astound the imagination – and, let’s face it, flooding the proud Manhattan is far more impactful than flooding a Siberian village, which we see on the news every spring.

We shouldn’t question why New York is already flooded and frozen in ice, while in nearby Washington, D.C., the lights are still on in offices. Or why all the country’s television stations are still operating, and residents still have electricity to watch the chilling reports. Or why the residents of frozen California find green palm trees just across the border in neighboring Mexico – as if vigilant customs officers turned back the global glaciation at the border.

All these minor “whys?” fade before the lavishly staged computer-generated landscapes: a suddenly developed typhoon tearing down the skyscrapers of Los Angeles; a giant wave engulfing Manhattan; unprecedentedly menacing clouds gathering in cyclopean funnels with steep, seething edges. It’s not all that far-fetched – viewers of the Discovery Channel might even mistake the work of Hollywood special effects labs for on-location footage of real tornadoes and storms.

The Underlying Message

Emmerich’s film has a very real takeaway: you leave the theater with a strong sense of the fragility of what we call civilization. Even the doubts that arose during the screening testify to this fragility: yes, indeed, in reality, such a catastrophe would not have a happy ending, and therefore, there would be nothing to film. Humanity would be squashed like a fly – where would you find room for plot development? Cinema is as conditional as theater.

On the other hand, global warming is a real process. The uncertainty regarding its consequences is real. The explosive growth of alarming trends is real. In other words, the film cares about a future that is under real threat. It remains to think about what to do before the day after tomorrow arrives.

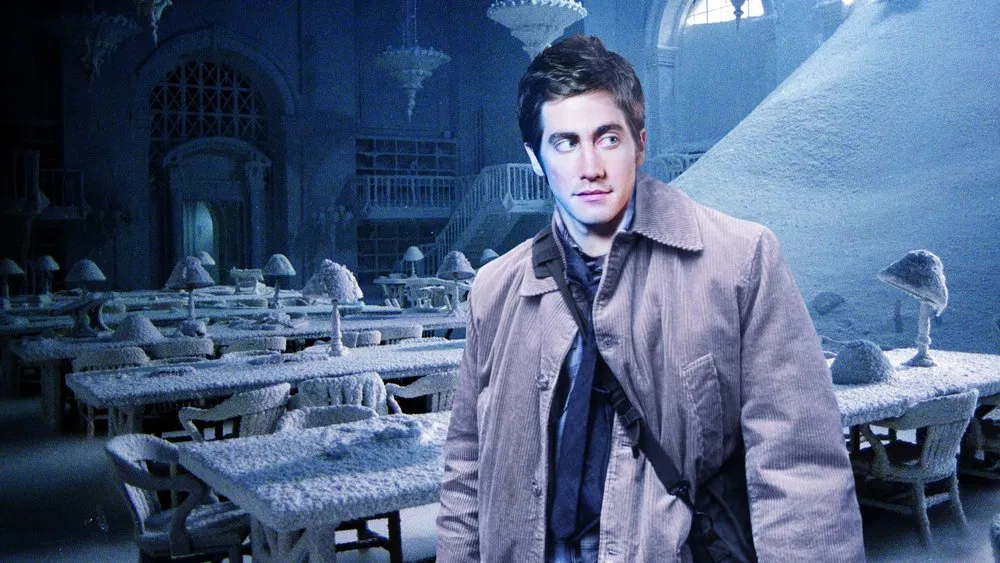

The film’s protagonist, meteorologist Jack Hall (Dennis Quaid), warns political leaders about the danger – they dismiss it, saying there are more important things to do. So, the words spoken in the film about neglecting science are also a reality, and one that is even more acute for today’s Russia than for the United States. No less important, despite the declarative presentation, is the final theme: the need to unite in the face of global problems.

I don’t know how Roland Emmerich positions himself in cinema, but I wouldn’t consider him an artist or expect outstanding works of high art from him. In the universal, multifaceted, and multi-genre space called cinema, he represents a kind of thematic park designer, where people not only have fun in haunted houses but also receive some useful information about the universe. It’s quite appropriate to have topical appeals and slogans scattered along the alleys, reminding us that we are human beings and that Earth is our common ship. And we are all to blame for the fact that this ship is visibly losing its buoyancy with each passing year.

Of all the possible plots in the film, the most standard and poster-like, but also the most relatable and understandable, is chosen: a son’s stubborn faith in his father and a father’s stubborn desire to come to his son’s aid. Americans never tire of talking about family values, understanding the family both as a cell of society and as society as a whole. And it must be admitted that, despite the banality of these values, it is in them that strength and hope lie. The fact that Emmerich’s quite craftsmanlike film is watched by millions, and his anxieties and values are inadvertently instilled in them, in my opinion, makes such cinema more important not only than the corrupting “Brigada” but also than the destructive “Taurus.”