The Fragility of Existence: A Reflection on Terrence Malick’s “The Tree of Life”

“When you set out to capture eternity, it’s best not to announce it too loudly.” This sentiment perfectly encapsulates the delicate and profound nature of Terrence Malick’s “The Tree of Life.”

The film centers around Jack (played by Sean Penn), who reflects upon his childhood, his complex relationship with his father (Brad Pitt), the nurturing presence of his mother (Jessica Chastain), and his bonds with his brothers. Through Jack’s eyes, we witness the evolution of his perception of the world, his initial encounters with emotional pain, and the inevitable disappointments that shape his understanding of life.

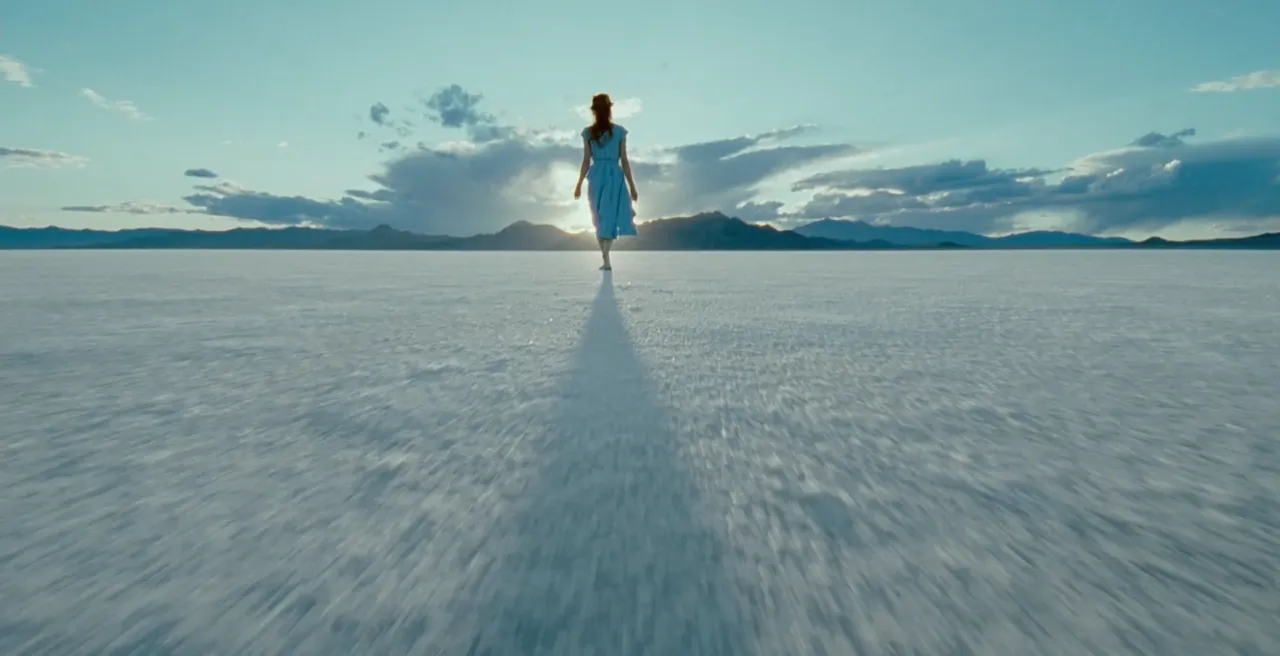

The film opens with the mother’s voice, articulating two paths one can take through life: the path of nature and the path of grace. Nature represents the easy way, following the current, while grace signifies the challenging path of love. “Unless you love, your life will flash by,” she says, highlighting the film’s central theme. Malick masterfully juxtaposes these two paths, the earthly and the ethereal, the fleeting and the eternal, offering a perspective intended to help us grasp the essence of existence. The genesis of life on Earth, a meteor’s descent, molten lava, billowing clouds, the rustling of trees, the coldness of stars, and children catching a frog – in Malick’s vision, these are all interconnected, facets of the same profound reality.

Memory as a Landscape

Jack doesn’t merely recall his childhood; he returns to it, immersing himself in a world frozen in time since the tragic loss of his brother. This death acts as a catalyst, compelling Jack (and perhaps his mother) to revisit and re-examine the events of their shared past. The boy’s death shatters the structure of their world, prompting existential questions – “Why? What for? Where is he now?” – questions that defy easy answers. To even begin to grapple with them, the world must be deconstructed, broken down into its constituent parts: a mother’s dresses, a cut on a heel, a family dog, a neighbor’s child with a skin condition. Malick achieves something extraordinary here, working with memory in a way reminiscent of Nabokov in “Speak, Memory,” reconstructing Jack’s childhood as a hierarchy of recollections. A chance encounter with a disabled passerby is etched in the child’s memory with the same clarity as the fear evoked by his father, a man who, despite his good intentions, often holds his son too tightly. Capturing memories subjectively is not a novel achievement, but Malick’s projection of memory is unique.

The camera doesn’t adopt Jack’s point of view, but it lingers on the boy with the skin condition as if he holds some significance to the plot, even though he simply made an impression on Jack’s young mind.

Nature’s Symphony and Existential Questions

“The Tree of Life” can be divided into two distinct parts: the memories and a molecular-cellular journey, reminiscent of Gaspar Noé’s “Enter the Void” and Darren Aronofsky’s “The Fountain.” These segments of the film raise the most questions. Nature has always been an endless source of meaning and metaphor for Malick, more of a character than a mere backdrop. However, in “The Tree of Life,” there are moments when it feels as though someone has secretly switched to a nature documentary. Jellyfish, fish, birds, frogs, dinosaurs, a wounded creature resembling the Loch Ness Monster – these creatures are interspersed with shots of matter and elements. The director’s intention is clear: to imbue the earthly with a divine depth. But the film already possesses that depth, even without the frogs.

“The Tree of Life” is an endlessly beautiful, melancholic, and incredibly tender film about life, time, memory, the fragility of reality, and the love that lingers in our hands even as everything else slips through our fingers. However, the film’s ambition (and its unrestrained use of biblical allusions) ultimately detracts from its overall impact.