Oliver Stone’s “Alexander”: A Pricey but Dull Epic

Surprisingly, the life of Alexander the Great has only been depicted on screen three times before Oliver Stone’s version. There was a silent film in the early 20th century, followed by a lackluster and pompous Greek production. In 1956, Robert Rossen directed the glamorous drama “Alexander the Great,” starring Richard Burton as Alexander and Danielle Darrieux as his mother, Olympias. For the most part, the impressively charismatic Burton sat on his throne, delivering eloquent speeches about valor, heroism, and glory. However, one might argue that if Alexander had stayed home, he wouldn’t have conquered half the world, nor would his soldiers have waded through the Indian Ocean.

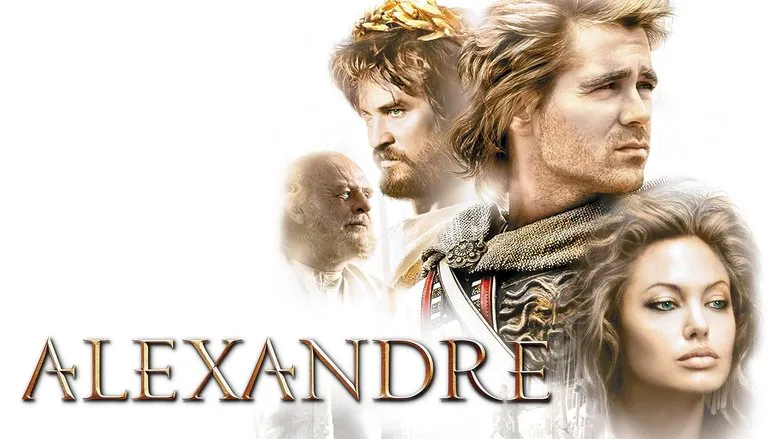

In Oliver Stone’s new film, “Alexander,” starring Colin Farrell, the focus is more on Alexander’s journeys and battles. He still speaks quite a bit, delivering Hollywood-style pronouncements (after all, he was tutored by Aristotle himself), and waxes poetic about sunsets and sunrises. However, much of his time is spent in conversation with his mother, Olympias (played by Angelina Jolie, better known as Lara Croft: Tomb Raider), and his close friend Hephaestion (Jared Leto). Interestingly, Jared Leto was a late addition to the cast, as Brad Pitt was initially slated for the role. However, Pitt’s then-wife, Jennifer Aniston, reportedly gave him an ultimatum: “It’s either that homosexual Hephaestion, or it’s me.” Such are the behind-the-scenes dramas that can shape the fate of art. As for Olympias, she’s portrayed as a top-tier femme fatale, evident in her narrowed, scheming gaze, the ever-present snake draped over her bare shoulder, and her overly intense affection for her son. It seems Oedipus and his complexes have left their mark here, suggesting that Alexander’s conquest of the world was fueled by a love-hate relationship with his mother. At least, that’s how the film portrays it.

However, it’s not Farrell’s Oedipal complex (and the mystery of why his hair was dyed in a way that left his roots dark) but rather his close relationship with Hephaestion that sparked outrage among modern Greek lawyers, who accused the director of distorting historical truth. They argued that Alexander the Great was never homosexual. In a sense, they’re right; in pagan Macedonia, the term didn’t even exist. People simply shared sexual experiences with whoever was available in bed. A woman was fine, but a man was just as good. The morals and terminology to describe such things hadn’t yet been developed. Moreover, Stone handles the homosexual theme with considerable tact, avoiding explicit displays and focusing on Alexander and Hephaestion’s declarations of eternal friendship, accompanied by passionate but chaste embraces. There’s not even a single lingering kiss. Furthermore, Alexander fulfills his masculine duties in the film, having both an official wife and several unofficial ones. Therefore, the lawyers who accused Stone of historical inaccuracy may have jumped the gun. Alexander the Great hardly needs defending. On the other hand, the Greek discontent is likely beneficial to Oliver Stone and the film’s producers. While it’s hard to imagine publicity on the scale of Mel Gibson’s recent controversy with Jewish groups, offended Greek lawyers are a decent substitute.

Analyzing the Film

Critically analyzing “Alexander” is akin to seriously discussing the artistic merits of comic books. If it pleases the eye, that’s the extent of the analysis. The artistic simplicity of one of the most expensive films in cinematic history (with a budget of around $170 million) is all the more glaring because of the director’s persistent attempts to mask it with various tricks. For example, during the famous battle with elephants in India, the leaves of the trees turn red and remain crimson throughout the battle, like autumn maples. For those who haven’t guessed, this is meant to symbolize blood and death. Original, isn’t it?

However, Stone, as an experienced director with a keen sense of political trends (as evidenced by his films “Nixon,” “Salvador,” and “Comandante”), knows that such tricks are no longer in vogue. Political allusions, subtle bridges to the present, are much more fashionable. In the current climate, Alexander’s justifications for his campaign against Persia resonate strongly. The Persian King Darius, it turns out, is a dictator, and Alexander’s mission is to liberate the Persians from their hated ruler. Yes, liberate, not conquer. One look at Darius is enough to convince anyone that the Persians don’t need him, just like Hussein in Iraq.

The entire story of Alexander is narrated in the film by an elderly, bald Ptolemy (Anthony Hopkins), who is now the ruler of Egypt. Anthony Hopkins is undoubtedly a great actor, but only a large sum of money could have persuaded him to take on such a muddled role, where his character confuses everything in time and space.

“Alexander the Great is a great commander, but why break chairs?!” exclaimed Gogol’s character. Ultimately, even breaking chairs is acceptable, but it should be done beautifully, with taste and a universal crash, not as lazily and without a hint of scale as it’s done in “Alexander.” There are only two battle scenes (considering that Alexander did little else besides wage war), and the romantic passions are limited to a light, non-committal scuffle on the wedding night with his fiery Asian wife, Roxana. You watch it and forget it.

Perhaps Jennifer Aniston was right to steer her husband away from this film. After all, a good actor belongs in a good movie, and, as they say, let Chaliapin sing operas.