Blow: A Retrospective Look at a Life Fueled by Cocaine

The premiere of “Blow” at the Horizon cinema was met with a peculiar reaction. During the opening scenes depicting the process of extracting cocaine from the coca plant, the audience erupted in laughter and applause, as if the theater had been filled with cocaine enthusiasts.

However, the audience also included esteemed figures such as Oleg Tabakov, Oleg Yankovsky, Alexander Porokhovshchikov, Alexander Mitta, Yuri Grymov, Arkady Inin, Ivan Dykhovichny, Vladimir Khotinenko, Natalya Belokhvostikova, Yulia Rutberg, and Evgenia Dobrovolskaya, who undoubtedly expected more from Ted Demme’s film.

The film, a two-hour saga, evoked mixed reactions. Without the central theme of cocaine, it would have been a rather ordinary drama about a man’s life.

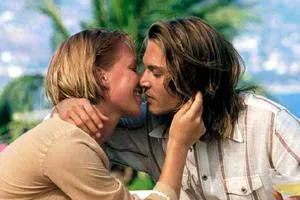

The story follows George Jung (Johnny Depp), a boy from a poor family who aspires to a better life than his parents (Ray Liotta and Rachel Griffiths). Driven by ambition, he enters the burgeoning American drug trade. He proves to be a shrewd businessman, quickly amassing wealth, falling in love, and experiencing fleeting happiness. However, his downfall begins when he is betrayed by his own mother, leading to his first prison sentence. After struggling to rebuild his life, he once again finds himself caught in the cycle of wealth and poverty. He marries Mirtha Jung (Penélope Cruz), has a beloved daughter, but is betrayed a second time by his self-serving wife. A third betrayal by his last remaining friend (Paul Reubens) leaves him utterly alone, facing a lengthy prison sentence that will likely last until his old age.

This narrative is a timeless tale. For someone born into poverty who desires to escape a life of hardship, a path to success is necessary. However, honesty and integrity are often incompatible with the pursuit of wealth, especially in a morally questionable business. This holds true for a noble drug dealer just as it does for any ambitious individual seeking to climb the social ladder.

“Blow” adds a few interesting touches to this familiar story. Firstly, the film chronicles thirty years of American drug trafficking history in a popular and unobtrusive manner. It is fascinating to witness the evolution of the trade, from its humble beginnings on ocean beaches to its infiltration of Manhattan’s bohemian circles, and the eventual involvement of the infamous Pablo Escobar. Secondly, the film’s retro aesthetic, featuring the fashion and culture of the 60s, 70s, and 80s, feels authentic and well-integrated. From bell-bottoms and disco dancing to poolside parties reminiscent of James Bond films and hippie gatherings around campfires, the film captures the novelty and excitement of the era. Thirdly, Johnny Depp delivers a versatile performance, transforming himself with long hair, blond hair, gray hair, mustaches, and clean-shaven looks. He portrays a character who is at times intoxicated, insightful, and ultimately, human. By the end of the film, it is difficult not to feel sympathy for him. The “family chronicle” segments, presented in short montages, are particularly effective.

The Downside of “Blow”

Unfortunately, these elements feel somewhat disconnected from the overarching drama. Hollywood’s approach to the topic of cocaine is often cautious. Despite aiming to create a “big movie” about the fast money of the modern era, the film ultimately succumbs to political correctness.

Ted Demme avoids fully exploring America’s transition “from innocence to cynicism, from marijuana to cocaine.” Instead, he relies on the biographical book about George Jung, who takes responsibility for his actions. While Jung is a real person, currently serving a prison sentence until 2015, and Depp even visited him, simply recounting someone else’s biography is not enough to resonate with the audience. To truly capture the shift “from innocence to cynicism,” the film needed to be more thought-provoking than simply retelling a story. It needed to examine the common denominator of “cocaine” and explore its impact on individuals, challenging assumptions and arriving at personal conclusions. This would have allowed the “fresh touches” to merge seamlessly into the narrative, transforming the story of drug trafficking in America during the 60s, 70s, and 80s into a personal exploration of the eternal loneliness that we must learn to accept. A retro-style film about eternal loneliness could have been both amusing and poignant. Ultimately, “Blow” is more disheartening than entertaining. In its pursuit of political correctness, even when dealing with a controversial topic, the film loses its ability to truly engage the audience. Big money, it seems, cannot coexist with anything eternal.