The Hollywood Romantic Comedy Machine: An Analysis of “Bridget Jones’s Diary”

It’s becoming increasingly clear that Hollywood has abandoned any pretense of artistic merit, especially when it comes to romantic comedies. The genre has been shamelessly commodified, with films like “Bridget Jones’s Diary” serving as prime examples of this trend.

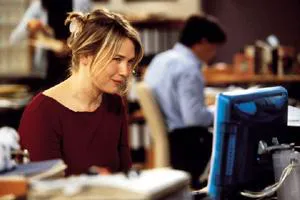

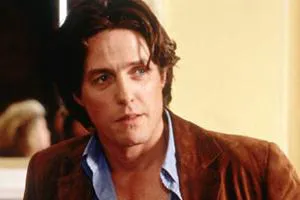

The film centers on Bridget Jones (Renée Zellweger), a slightly-over-thirty editor struggling to find love. She becomes involved with her charming but unreliable boss (Hugh Grant), who inevitably breaks her heart. Bridget then quits her job and becomes a television personality. All the while, a dependable and kind man (Colin Firth) patiently waits for her. The story unfolds through Bridget’s diary entries, chronicling her weight fluctuations, increased alcohol and cigarette consumption, and increasingly unfiltered thoughts. This guarantees humor and vivid details. For instance, we learn that wearing a black mini-bikini on a date ensures no sex, while donning oversized underwear guarantees a skirt-lifting encounter. These are the kinds of “laws” that, surprisingly, often hold true in real life, and Bridget’s diary is full of them.

The film might have been considered somewhat original if it hadn’t been preceded by a string of similar movies in recent months, including “Animal Husbandry,” “Nurse Betty,” “What Women Want,” “Where the Heart Is,” and “Me, Myself & Irene.” However, “Bridget Jones’s Diary” attempts to differentiate itself through self-deprecating humor.

“Pride and Prejudice” Reimagined

The film is essentially a modern-day retelling of Jane Austen’s classic novel, “Pride and Prejudice.” The character of Mark Darcy, famously portrayed by Colin Firth in a BBC adaptation years ago, is reimagined as the “good boy” in “Bridget Jones’s Diary.” He’s the ultimate dream man: tall, handsome, intelligent, honest, and single.

This highlights the commodification of romantic ideals, reaching its peak in films like this. In “Animal Husbandry,” Ashley Judd faced similar romantic dilemmas while working in television, albeit at a younger age, resulting in less humor. “Where the Heart Is” featured a young woman abandoned by a “bad boy,” enduring hardship until she meets a “good boy” and becomes a successful photographer. Interestingly, Ashley Judd played a humorous supporting character, juggling multiple children while searching for a husband. “Nurse Betty” takes a darker, less comedic approach, but still adheres to the formula: a “bad boy” and the dream of a “good boy,” with the heroine finding fame on television, played by Renée Zellweger. In “Me, Myself & Irene,” Zellweger is again the object of affection for two men, one “bad” and one “good,” both played by Jim Carrey, who both love her “as she is,” flaws and all.

Hollywood’s Collective Therapy Session

It’s tempting to conclude that Americans are now so wealthy and stingy that they’re unwilling to pay for individual therapy, and Hollywood has capitalized on this. The benefit of collective psychoanalysis is that the rest of the world can now observe the American psyche. These films reveal what Americans are “really like,” catering to their desires. However, it’s well-known that romantic comedies stem from a deeply neurotic “need for love.” According to psychological theory, this neurosis reflects a profound fear of life, and judging by the sheer volume of these films, the entire American nation seems to be infected.

This fear manifests as a rejection of real life, with characters existing solely within the realms of television, advertising, and show business. Humor serves as a mask for this underlying anxiety. Furthermore, while psychoanalysts once attributed this “love need” neurosis to women, it now seems to afflict American men as well. In “What Women Want,” Mel Gibson, a single father and advertising executive, gains the ability to read women’s minds and chooses his eternal love from two beautiful women.

The Hope for a Real-Life Darcy

On the other hand, who knows? If the same message is repeated month after month, year after year, century after century, perhaps a breed of real-life, unmarried men – tall, handsome, intelligent, and even honest – will emerge from these collective fantasies. But in this scenario, Hollywood is merely an old, tired medic with limited resources, and we can only hope it doesn’t botch the delivery.