During a screening, a conversation unfolded:

– Why aren’t they arriving? Is it a flop?

– The theme song is nominated for an Oscar. They won’t arrive until it’s sung.

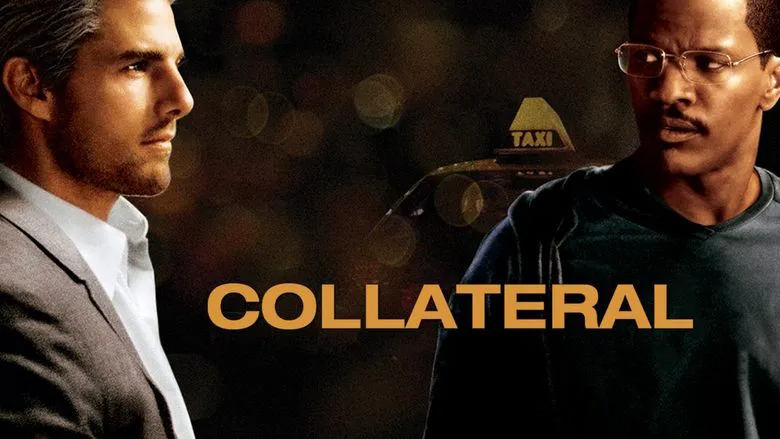

Michael Mann’s “Collateral” has broad appeal. Set at night, it evokes a sense of boogie-woogie. The digitally rendered Los Angeles lights are reminiscent of Andy Warhol. The classic lone-killer plot echoes “The Samurai,” and the dramatic conflict between executioner and victim is reminiscent of Dürrenmatt, lending an existential quality to the thriller. Two underachievers spend a short time together in close quarters. One has been a hitman for six years, acting on instinct. The other has been fantasizing for twelve years as a taxi driver. The passenger’s professional obligations involve five murders, which the taxi driver inadvertently turns into ten because they spend the entire journey sorting out their relationship, which is deadly. Who works harder, who wins less, who is a coward, who is a fool, who is better to be, and who is better to seem. The witty dialogue (script by Stuart Beattie) – “Open the trunk, and that’s where they’ll lie,” “My son only does something for his mother at gunpoint” – is comparable to Mann’s best thriller, “Heat.”

A Film About Life and Oscar Ambitions

In short, it’s a film about life with “Oscar” ambitions, as evidenced by its quickly recouped $65 million budget. There is no complete happy ending, and Mann was not the first choice for the project. Scorsese, Spielberg, and Spike Lee were considered. Before Tom Cruise, Russell Crowe and Edward Norton were in the running, and before Jamie Foxx, De Niro and Adam Sandler were considered. Due to the careful selection process, Jamie Foxx immediately became a star. Tom Cruise looks great with his gray hair and finally realizes his eternal ambivalence – both a monster and a strong man. Finally, Barry Shabaka Henley delivers a brilliant performance in the jazz club scene, and everyone else – Jada Pinkett Smith, Mark Ruffalo, Javier Bardem – is well-cast. “Collateral” is a stylish quintessence of current issues of violence and non-violence, terrorism and anti-terrorism, filmed in an accessible genre. What follows are not spoilers (there are few mysteries in “Collateral”), but specific questions about what is currently being passed off as quintessence, turning stone into gold.

Unanswered Questions and Plot Holes

Why did Tom Cruise scout the last prosecutor’s office on the list when he didn’t scout any of the other clients, killing them on the fly? A more relevant location for scouting would have been the nightclub, where it’s difficult to assess the situation on the fly. Was it just so he could get into Jamie Foxx’s taxi, which had dropped off the prosecutor? Why is the assistant prosecutor for the drug cartel case on the list at all? Drug lords need to eliminate witnesses or, at worst, their corrupt drug lawyers to avoid imprisonment.

Who was killed during the taxi search with the body in the trunk, just so the police could leave without opening it? Even by midnight, Los Angeles only had four fresh corpses, all of which were Tom Cruise’s doing. Why go to a jazz club, discussing the starry sky above us, which has nothing to do with the moral law within us, instead of dumping the body in the trunk into the ocean after just getting caught with it? Would the police respond so quickly to a dubious alarm if they were already suspicious of a taxi driver with a broken windshield and an arrogant passenger, when the trunk opens in half a second?

Why is Tom Cruise so concerned about going to the hospital to see Jamie Foxx’s mother? He believes that not doing so would disrupt the status quo and lead to a search for the taxi driver, even though he just forced the taxi driver to disrupt any status quo by cursing out his boss for the first time in twelve years, which didn’t alarm the latter. Was it just to sort out their relationship during the touching trip and then warn him: “You have ten minutes. On the eleventh, I’m driving to the hospital and taking out your sick mother”?

Why does Jamie Foxx have nowhere to run from the hospital except onto a long overpass, where he is visible for hundreds of feet instead of hiding behind a corner, a door, or pretending to be a mop? He keeps looking back, stopping while running, just to get caught?

How can a professional killer call five client addresses, three of which have already been eliminated, a “lost archive” without which he cannot complete the order? The remaining two addresses include the one where it all started, the prosecutor’s office, which is easily recognizable in Los Angeles. If the entire operation is sold to us as a “fully prepared third act of the drama,” did the professional killer have severe amnesia during the first two acts, unable to learn five addresses?

Why did the head of the Los Angeles FBI decide that the priority was to kill the hitman when the taxi number had already been identified, helicopters were circling it, and it was known to be heading to the nightclub? Why did the sniper team spread out at the nightclub among crowds of innocent people and flashing lights, far from the witness they didn’t even protect, even though the crowds weren’t hostages? Is this a film about Beslan? Or was it so the snipers could eliminate everyone except Fox and Cruise, who eliminated the witness like a child in the chaos and quietly slipped away with the crowd?

If it’s obvious that the taxi has been identified, why do they get back in it when there’s a parked car dealership near the nightclub? How did the taxi driver with a compromised number manage to get from the slums to the city center without a single road patrol while helicopters were circling?

How did Jamie Foxx, standing far away across the overpass, see not just a black figure but Tom Cruise in a gray suit on the 14th floor of the prosecutor’s office at night? Does he have a telescopic lens instead of eyes? Did Cruise scout the building just to figure out which lock to hit with a crowbar to cut off the electricity on the 16th floor, leaving it on for everyone else? Or did Jada Pinkett tell him in advance that she would be in the library at four in the morning, not in her office on the 14th?

Why, when Cruise clung to the last car of the subway and walked through the entire train looking for Fox and Pinkett, did they hide and run out of the last car at the next stop? Finally, why does Cruise wear small, very black glasses at night that don’t change his appearance but stand out in every corridor like the fairy-tale cat Basilio?

We can ignore the wounds, catastrophes, and other inconsistencies. But in Hollywood, the half-century-old originator of “film noir,” which “Mean Streets” (1973), “Bad Lieutenant” (1992), “The Usual Suspects” (1995), and other masterpieces strictly inherited, it cannot be unknown that one or two script stretches are forgivable in “noir” cases for the sake of plot coherence. When every frame has a stretch upon a stretch, instead of a quintessence of a thriller, it’s a hodgepodge. All the rhythm and drive are completely lost, the supposedly killer episodes are boring, professionalism is a profanation, humanism is political technology, and sorting out relationships is stupidity. Initial suspicions are replaced by middle irritation, which turns the thriller into a comedy by the finale, and after a bullet hits Tom Cruise’s earlobe, all that’s left is to giggle quietly and comment sarcastically. Instead of turning stone into gold, Michael Mann and Stuart Beattie wanted to turn us into complete idiots. That’s the delivery – everything is in place, but everything is a setup and not what it seems.

When humanity became stupid, it first stopped being humanity, leaving only Pavlov’s dog’s light bulb for correspondence. The light bulb is on – a thriller for the whole pack, an Oscar for the film crew. But we’ve probably been lied to too much lately to be fooled even once. “Collateral” is as much a fake of life as the news reports from Beslan are of eyewitness accounts.