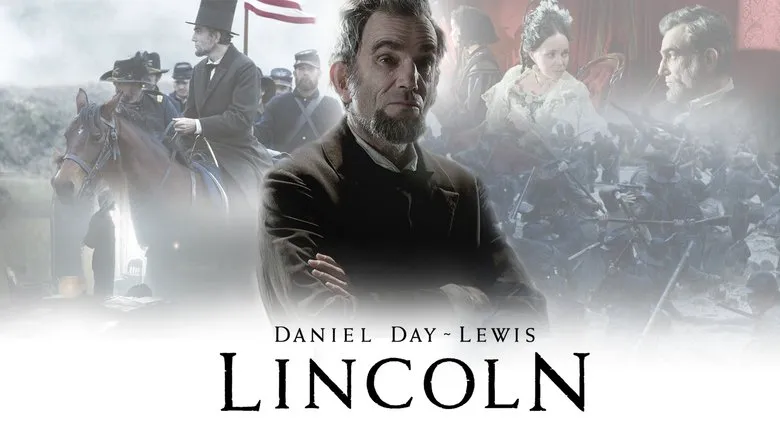

Lincoln: A Decade in the Making by Spielberg

A vivid portrayal of Abraham Lincoln (Daniel Day-Lewis) as he navigates the treacherous waters of Congress, employing every tactic at his disposal to secure the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution, effectively abolishing slavery.

When a director tackles a presidential biopic, the president invariably reflects aspects of the director’s own persona. Oliver Stone imbued Nixon and John F. Kennedy with his signature brand of fervent paranoia, and lampooned George W. Bush in “W.” In Steven Spielberg’s nuanced film, the 16th and arguably most revered U.S. president emerges as both a natural showman and a calculating intellectual. This Abraham Lincoln shares more than a little with Spielberg himself.

Drawing inspiration from Doris Kearns Goodwin’s acclaimed biography, “Team of Rivals,” a book favored by Obama, screenwriter Tony Kushner crafted a monumental 550-page script detailing Lincoln’s political life. Spielberg, narrowing his focus, chose to adapt the final 80 pages of this epic. This decision to eschew the traditional biopic formula and instead spotlight his protagonist at a pivotal moment in his life stands as one of the most brilliant choices of Spielberg’s career.

Fun Fact: Hal Holbrook, who plays Republican Party founder Francis Preston Blair, has portrayed Lincoln himself three times: in the 1974 miniseries “Lincoln,” the 1985 miniseries “North and South,” and in a sketch on “The Ed Sullivan Show.”

A Focused Narrative

The film dispenses with Lincoln’s humble Kentucky beginnings, his ascent to power, and even the Gettysburg Address. The Civil War unfolds through fragmented reports. Family matters are relegated to subplots: his eldest son Robert (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) clashes with his father over enlisting in the army, while Lincoln, burdened by the sacrifice of countless other sons, tries to protect him. His mentally fragile wife, Mary (Sally Field), torments him with headaches and heartbreak, while simultaneously casting menacing glares at his political adversaries.

“Lincoln” concentrates entirely on the tumultuous final months of his second term, specifically his relentless pursuit of the Thirteenth Amendment’s ratification. While this subject matter might seem dry and verbose, it proves to be both captivating and, yes, verbose. Knowing that the very soul of the nation hangs in the balance, Lincoln, remarkably, chooses to prolong the war to ensure the amendment’s passage.

Kushner’s intricate script demonstrates a keen understanding that delaying the amendment’s adoption until the South’s reintegration would have doomed its chances, perpetuating slavery. What emerges is a powerful ode to democracy in its most crucial form – a biography of a political moment. Spielberg demands our undivided attention, yet the film remains accessible: compelling, visually stunning, and populated with memorable characters.

Visual and Aural Storytelling

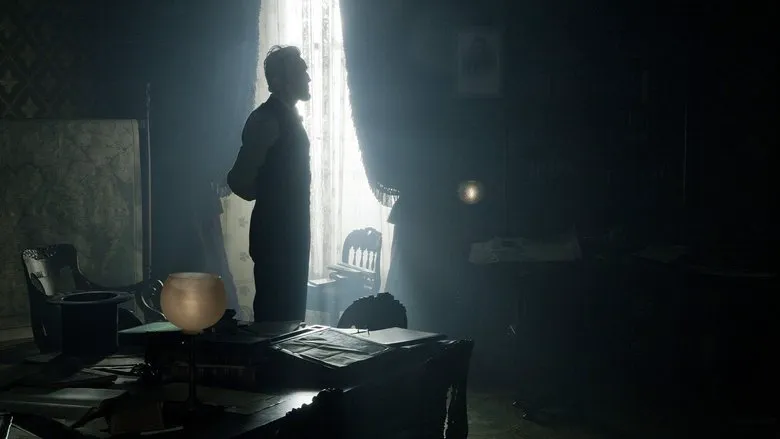

Every line, every frame of “Lincoln” resonates with purpose. Image and sound coalesce seamlessly: the camera seems to speak, and words come alive before our eyes. While some have criticized Spielberg for being overly cerebral, the masterful framing and rich, dark-coffee hues refute these claims. Light, filtering through clouds of tobacco smoke and dust, takes on a tangible quality. And the vast ensemble cast delivers performances brimming with energy and commitment.

Day-Lewis based his vocal portrayal of Lincoln on accounts from contemporaries, who described the president as having a tenor voice, which contributed to his reputation as a great orator in an era before amplification, when higher voices carried more clearly.

Lincoln’s Pragmatism

Lincoln employs every tool at his disposal to achieve his goal: arguments, persuasion, threats, bribery, a carefully curated repertoire of folksy anecdotes, and, in a sensational scene with his exasperated cabinet around a smoke-filled table, sheer force of will. “I am clothed in immense power!” Daniel Day-Lewis thunders, slamming his fist on the table as tensions escalate. He cajoles wavering members of the House of Representatives, where, in 1865, the political convictions of Democrats and Republicans were the polar opposite of what they are today.

Rather than simply polishing the legend etched on Mount Rushmore, Spielberg strips away the varnish, revealing the raw pragmatism beneath. To achieve his aims, the idealist must twist arms and grovel before the powerful. It turns out that Honest Abe could be a lying SOB when necessary.

Spielberg’s attention to detail extended to recording the ticking of Lincoln’s actual pocket watch, housed at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum in Springfield, Illinois.

Humor and Satire

“Lincoln” is often surprisingly funny. The scene where three slippery agents, led by the mustachioed, foul-mouthed James Spader, are dispatched to woo (or intimidate) wavering congressmen is almost farcical. And Tommy Lee Jones steals every scene as Thaddeus Stevens, the staunch abolitionist who is persuaded to temporarily abandon his “all or nothing” principle. It is said that Stevens, when “fired up,” could tear his trembling opponents to shreds; a similar ability, according to terrified interviewers, is possessed by Mr. Jones.

For decades, rumors have persisted that a recording of Lincoln’s voice was made at the White House in 1863 using a device called a phonautograph. The recording has never been found, and remains something of a Holy Grail for Civil War scholars.

A Modern Masterpiece

In terms of associations, the Coen brothers come to mind. Here is a quintessentially American scene, in which stubborn men with ridiculous facial hair exchange insults: a baroque compendium of Twainian eccentricities, Shakespearean oratory, biblical precepts, and the florid PR of the time, crowned by perhaps the most scathing use of the phrase “wretched creature” in cinematic history. Kushner nudges the director toward satire, for what are politicians if not actors, and what is the House of Representatives if not a theater? Yet there is no doubt about Spielberg’s seriousness of purpose. In a desire to glimpse the world beyond the lamplit confines of Washington, Lincoln rides on horseback through the ruins of Petersburg, littered with corpses… sometimes, to do good, one must resort to terrible evils.

Perhaps it is highly symbolic that the schizoid heart of American history is played by Day-Lewis, half English, half Irish. Having been Hawkeye in “The Last of the Mohicans,” the brutal, flag-draped Bill the Butcher in “Gangs of New York,” and the soulless magnate Daniel Plainview in “There Will Be Blood,” he has now become the great liberator, Lincoln.

Unpredictable and, thanks to the masterful work of Spielberg and Kushner, intellectually stimulating, “Lincoln” is a true milestone in film history. And Day-Lewis is so convincing that you’ll want to tip your top hat to him.

The actor, unparalleled in his preparation for roles and study of his characters, cranes his neck and tenses every muscle to convey Lincoln’s gait, which contemporaries described as wooden. Day-Lewis is awkward, almost Robocop-like, his nasal voice constantly seeming dissatisfied, and it takes some getting used to. His character is thoughtful and diplomatic, his hesitant smiles fleeting, he dresses like an undertaker, and has a habit of, apropos of nothing, quoting Euclid and “Hamlet.” Spielberg envelops him in shadows and crowns him with a silvery halo: unfortunately, the final five minutes of the film are completely superfluous. It seems that their only purpose is to hastily restore Lincoln’s image as a saint before the melodramatic ending, because these shots are a short study on the very directorial rationality: with the honed concentration of a swaying tightrope walker, Day-Lewis maintains the tantalizing balance between a living man and a marble statue.

When we first see his Lincoln, the president sits in a pose so familiar from the future memorial, his back to the viewer and his face to the orchestra, listening as black soldiers, demonstratively addressing him, chant words from his own Gettysburg Address. The meaning of what is happening is crystal clear: promises must be kept.