“Lion”: A Tearjerker with a Hidden Agenda?

The creators of “Lion” skillfully manipulate viewers’ emotions, but behind the tragic story of a young boy separated from his mother lies no profound message, just a subtle promotion of Google. Well, OK…

Five-year-old Saroo lives with his mother, sister, and two brothers in a remote, impoverished region of India. In search of food and small earnings, he and his brother venture to a nearby town’s train station. By a twist of fate, Saroo becomes a “prisoner” on a train heading to Calcutta, 1,500 kilometers from home. Unable to speak the local language or recall the name of his hometown, Saroo becomes a street urchin and eventually finds refuge in an orphanage for lost children like himself. A year later, luck smiles upon the boy when an Australian couple adopts him, whisking him away to another continent and showering him with love and care, seemingly erasing memories of his lost home. However, the image of his mother and brother haunts Saroo. Twenty-five years later, as a student, he uses Google Earth to locate his Indian home. After three years of searching, fortune favors the young man.

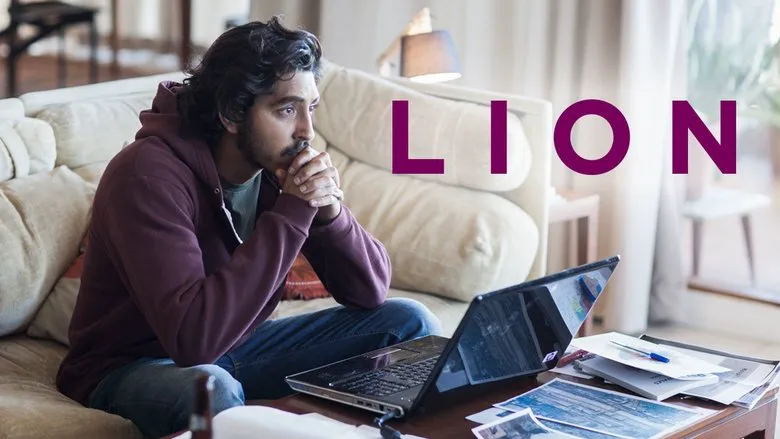

.jpg “A scene from “Lion””)

.jpg “A scene from “Lion””)

Google provided the filmmakers with satellite imagery archives and software from 2008-2011, the period when Saroo actively used the internet for his search.

Life is Stranger Than Fiction

Reading numerous articles about Saroo Brierley’s life, one is reminded that reality is often more inventive than any fictional story. “Based on true events” narratives have a significant advantage over pure fiction. If a writer had conceived the story of a lost boy finding his way home after a quarter of a century, the novel would likely end up as a paperback sold at a train station kiosk. But life… life is such that the banality of reality is not only forgivable but warmly embraced by the public.

“Lion” became the largest film production in Tasmania, Australia, surpassing even “The Light Between Oceans” in budget and local employment.

Saroo’s story has become a beacon for melodrama enthusiasts: poverty, maternal and fraternal bonds, a tragic accident, loss of direction, hunger, big-city dangers, orphanage, adoption, a foreign family, and a completely different life – enough to stir the heart. But whether it was worth making a film out of it is a big question. Or rather, should such a film have been made about Saroo, and should a debut director have been entrusted with the task? Perhaps not.

Despite the heartwarming nature of the story, Garth Davis’s film doesn’t quite reach the level of profound drama. Of course, one would have to be completely heartless not to shed a tear by the thirtieth minute, but a detached perspective half an hour after the credits roll will tell you that the child’s suffering is just one way to move you. Yes, the tragedy of a child losing his home is present, and the return home is equally touching, but the plot twists in “Lion” barely suffice for a “Special Correspondent” report or a libretto for a talk show. Two hours of “Lion” is an open invitation to wallow in sentimentality and soak up tears.

Uneven Directing and Emotional Impact

Furthermore, the film’s direction is not entirely successful. The film is divided into two equal parts, too dissimilar, executed in different styles, lacking rhythm and tempo, and even acted in opposing keys. While the first hour is a showcase for young Sunny Pawar, whom the cinematographer clearly admires for his naturalness and spontaneity, the second half tries, unsuccessfully, to please several actors at once, preventing them from showcasing their full talents. Although they try – the Academy has already recognized Nicole Kidman’s monologue about adoption (powerful, albeit fleeting) and Dev Patel’s diligent tears mixed with the character’s obsessive search (admittedly forced).

(Video player and related code removed for brevity)

This division results in a noticeable emotional failure. After an hour of rapid escalation, the plot quietly releases the air, the balloon of feelings deflates, and viewers arrive at the finish line tired, albeit satisfied. The film includes touching “hugs” from the reunited family and footage of the real Saroo, Sue, and Lucy. Despite the extraordinary story, Davis’s film falls victim to the same naivety that marred “Slumdog Millionaire” – India once again appears as a wild country, solutions to problems are superficial (Saroo found his family using Google and Facebook, and Jamal earned a million by answering a question for a fourth-grader), and the authors’ main weapon remains the active stimulation of tear ducts. Housewives will be delighted, but otherwise – life is once again more interesting than cinema, and much more tragic.