The Communist Spirit in “The World’s Fastest Indian”

Vladimir Mayakovsky was wrong to end his life at 37, driven by a morbid fear of old age, as Karabchievsky suggested. He was equally mistaken in proclaiming that “communism is the youth of the world, and it is for the young to build it.” Communism, in essence, represents the old age of the world, a concept vividly illustrated in Roger Donaldson’s film “The World’s Fastest Indian” (2005). The key difference lies in the fact that a fulfilling old age isn’t born out of the Soviet model, where the “youthful endeavor” culminated in primal hatred a century later. However, when participation is voluntary and driven by genuine enthusiasm, widespread happiness can indeed be “built.” In essence, Donaldson crafted a tale about a communist at heart.

The real Burt Munro, a motorcycle racing legend, was born in 1899 in Invercargill, New Zealand. He set his still-unbroken record on his 1920 Indian Scout at the age of 62, after retiring and with grown children. He continued to set records at the Bonneville Salt Flats (Utah, USA) until his death in 1978. Wikipedia remains silent on Burt’s wives, but that’s a minor detail. Donaldson, an Australian who moved to New Zealand in 1965, had the opportunity to meet and film the legend. Now in his early 70s, Donaldson, after directing films like “Bounty” (1984), “Dante’s Peak” (1997), and “Thirteen Days” (2000), faces similar challenges as Munro. His son has already become a New Zealand legend as a two-time Olympic champion runner. Donaldson, familiar with communist ideals, cleverly continued the old Hollywood tradition of “retirement follies” (“Amos” (1985) with Kirk Douglas, “The Straight Story” (1999) by Lynch) with “The World’s Fastest Indian,” drawing from real-life inspiration.

Burt Munro: A Portrait of a Communist

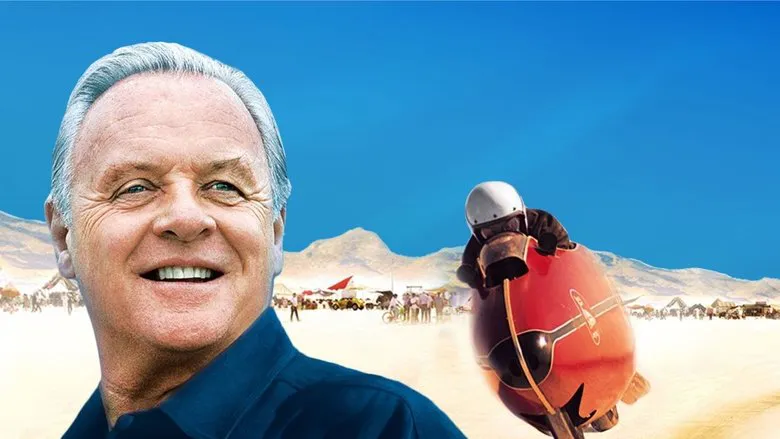

Burt Munro (Anthony Hopkins) lives on a pension, sleeps in his garage, urinates on his lemon tree, and neglects his lawn. He casts parts and tinkers with his motorcycle for half a century after work. It’s all logical, but it irritates his neighbors. Burt then suffers a heart condition before his long-awaited trip to America but embarks anyway, armed with a handful of nitroglycerin pills. What follows is a road movie from Los Angeles to Utah, filled with quintessential 1960s encounters: a transvestite, a Latino, a widow, and a soldier on his way to Vietnam. Then come the races themselves. That’s it. The film meticulously and deliberately explores the lifestyle of a true communist, then quickly glances around, then people relax, and all that remains is the increasing speed of the motorcycle. It’s like a person waiting, waiting, waiting their whole life, and then – bam! – everything comes true at once. But this fulfillment comes with a condition: don’t be foolish while waiting. And the film, like Burt Munro, never falters in its reactions to immediate circumstances. The only criticism is the abundance of overly kind people – logically rare unless you’re in the company of oligarchs or ministers. But that’s the point, and who knows how willing people were to part with their money without a fight in the early 60s, shortly before the “color revolution”? Perhaps they were.

The Oleographic Ideal of Old Age

Regardless, Donaldson’s depiction is exemplary. One can reminisce and savor how Hopkins interacts with motors, helmets, women, transvestites, Native Americans, and race officials. Prostatitis – what’s not to understand? No money, and prices are sky-high. The container is damaged, a wheel falls off, and a taxi driver rips him off. The organic nature of old age and its inherent irony (when the motel bed shakes deliberately) allow one to maintain complete communist composure in any situation. Should old age always be an exacerbation of vice if it’s unknown when it will end? Free, having lived to see it. This is a crucial aspect of “The World’s Fastest Indian,” especially relevant in the context of our civilization’s aging. The pretty girls at the races appear as biblical simpletons, and normal people only sleep “with their own” (peers). The norm is to know your worth, and “whoever betrays their dream turns into a vegetable.” A viable option is presented.

The One Shortcoming: Speed

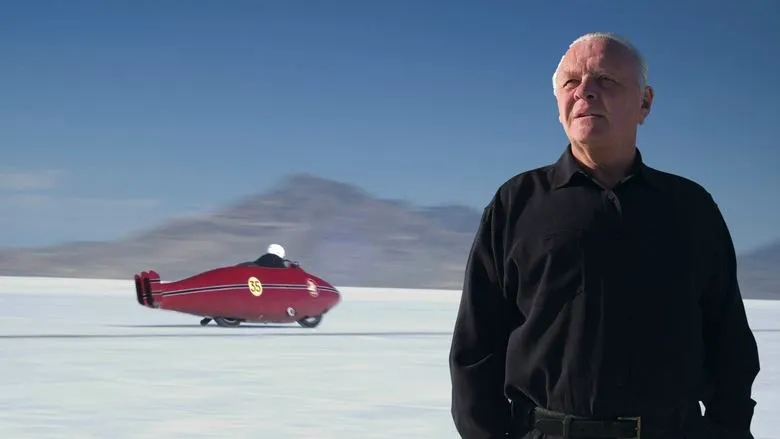

The only thing that confirms Donaldson himself might not be a viable option is the depiction of speed itself. He doesn’t know how to film it. After all the “Dante’s Peaks,” he still hasn’t figured it out. In the beginning – when Hopkins skillfully overtakes young bikers on his local beach – he still managed. But in the most crucial moment, when it needs to be breathtaking, the film veers into psychology. “Burned his leg,” “heart attack,” words, words, words – but he lacked the spirit for a fully subjective camera and editing (like in the first “Fast and the Furious” (2001), “Easy Rider” (1969), or the recent animated “Cars” (2006)). Against the white salt background, all the shots are taken incorrectly, from the side or without risk, and immobility creeps in. And psychology no longer compensates.

Perhaps he should have made his son, the Olympic runner, a speed consultant…