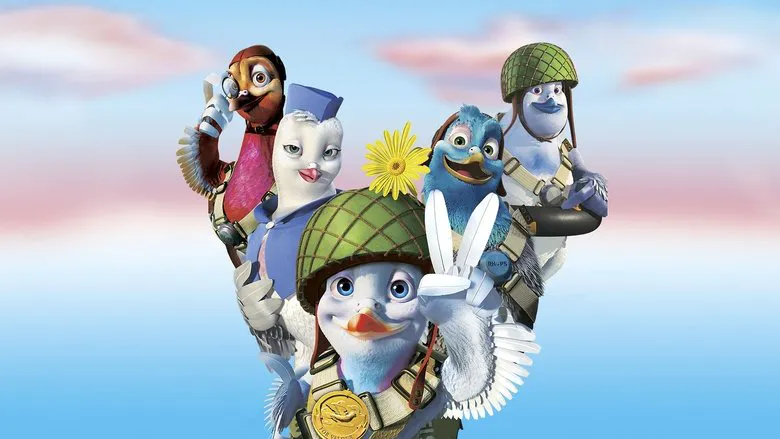

A Fresh Look at “Valiant: A Pigeon’s Plucky Adventure”

It’s often the technical aspects that dominate discussions about animated films. Take “Valiant: A Pigeon’s Plucky Adventure” (2005), for instance. While the English-speaking audience enjoys the original voices of Ewan McGregor, John Cleese, and Jim Broadbent, the dubbed versions often focus on the quality of the translation. However, a good translation can capture the spirit of the original, like when the German hawk interrogates a captured Allied pigeon with, “Where are the chickens? Where are the eggs?” – the translators clearly understood the humor the filmmakers intended.

World War II, a defining event of the 20th century, has influenced countless artistic endeavors. Theodor Adorno famously stated, “After Auschwitz, there can be no poetry.” Yet, even before him, Ernst Lubitsch dared to create a comedy about the war with “To Be or Not to Be” (1942). While some patriots may have viewed it with skepticism, audiences flocked to see it. Later, when Christian-Jaque released “Babette Goes to War” (1959), using the war as mere backdrop for Brigitte Bardot’s hairstyle, Soviet critics were outraged, while Soviet women embraced the “Babette” hairstyle. Gary Chapman, the debut director of “Valiant,” may not be intimately familiar with all the historical details, but he seems to have absorbed the inherent absurdity of the era. He’s crafted an animated film that’s arguably more radical than even Roberto Benigni’s Oscar-winning “Life is Beautiful” (1997). Living in the 21st century, World War II is not a defining event for him, but rather a springboard to explore his own themes, specifically those related to pigeons.

A Stylish Take on a Classic Theme

The story of a diminutive pigeon yearning to become a hero in the fight against the enemy is cleverly stylized. Instead of a generic fairytale kingdom, we see a recognizable Trafalgar Square, complete with Nelson’s Column. The film features vintage trains, planes, and battleships, and the pigeons and hawks are dressed in period-appropriate attire. This juxtaposition of “pity for the bird” with the realities of war creates a dizzying effect. The film embraces the irony towards heroes and villains that has long been present in live-action war movies, but now it’s fully animated and emotionally resonant. The hawk general seems to have stepped straight out of a classic fairy tale, while the enemy headquarters resembles a contraption from a Soviet-era film. A French Resistance mouse, voiced in the style of Edith Piaf, evokes the image of a spy in a car with a pastor. The final passionate kiss between the pigeon and his sweetheart is reminiscent of a news report about a London monument commemorating a kiss between a soldier and a nurse. The visuals are universally recognizable, even outside of America, and the film playfully subverts the stereotypes of “war movies.” The scale and perspective are well-executed, and “Valiant’s” love for cinema is comparable to that of “The Triplets of Belleville” (2003).

A Modern Perspective on War

Being a Hollywood production, Gary Chapman approaches the themes of “war” and “enemies” with a progressive 21st-century sensibility. He uses World War II as a lens to satirize modern conflicts. His answer to the question “Why do we fight?” is far from the patriotic spirit of Frank Capra. Other “modern” details, such as con artists and the first moon landing, also make an appearance. “Valiant” successfully fulfills its ironic, visual, and topical goals, making it a commendable debut. It’s a film that our children can enjoy, and it’s certainly preferable to something like “Beavis and Butt-Head” (1993-1997). However, when compared to the established archetype of “Shrek,” it falls short. It’s simply not as funny. While the creators of “Shrek” had free rein to mock film and television stereotypes, “Valiant” is confined to a specific and narrow cinematic and television theme. This theme doesn’t quite sustain the length of a feature film. The characters are somewhat derivative. The loud and obnoxious Bugsy is reminiscent of both Shrek’s Donkey and Winnie-the-Pooh, while the refined pigeon of noble birth resembles Eeyore.

Perhaps Chapman simply lacked the time to fully develop all the original details. The producers tasked him with completing the film, with a substantial budget of $40 million, in just two years, to coincide with the 60th anniversary of the end of World War II (September 2nd). Without the time constraint, the film could have been even better.