Deep in debt, inventor Wallace and his faithful dog Gromit are brainstorming ways to settle their bills and earn some money. Wallace comes up with a stroke of genius: renting out an AI-powered garden gnome to help with gardening. Despite Gromit’s frustration with the excessive mechanization of household chores, the business quickly pays off.

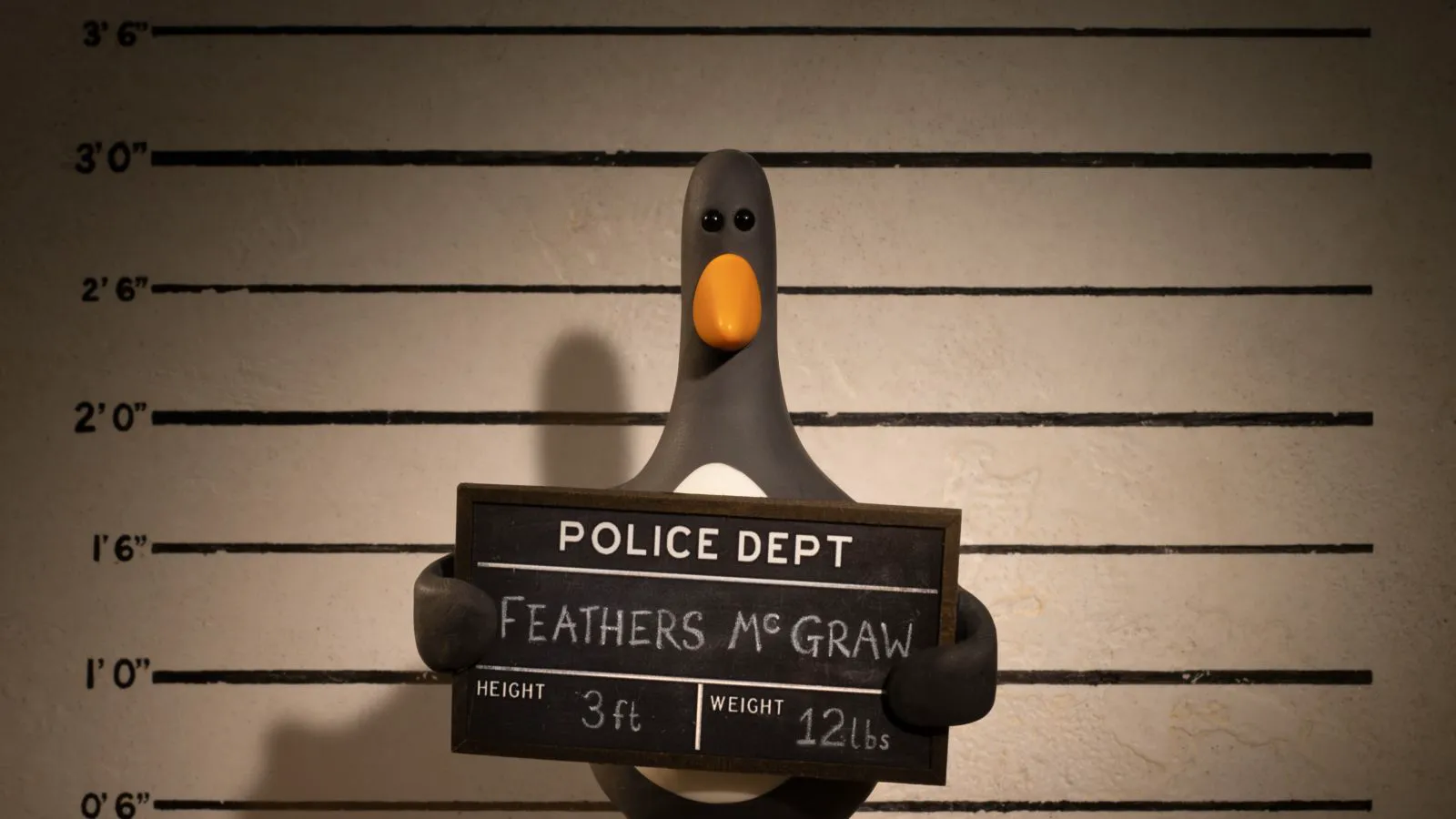

However, news of their popular invention reaches an old acquaintance of the duo: Feathers McGraw, the penguin serving a life sentence at the zoo. Wallace and Gromit once caught the villain who planned to steal a rare blue diamond (“The Wrong Trousers”). McGraw decides to exact a nasty revenge by reprogramming the garden gnome, attempting to seize the precious gem for a second time, and even framing the naive Wallace.

Still from the animated film “Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl”

Aardman’s Legacy and Recent Struggles

It seems like only a decade ago, the release of a new feature film from Aardman Animations felt like a holiday, regardless of the chosen setting or franchise. It was clear that the masters of clay animation would find a way to tell a charming story, pack it with references to classic world cinema, and, of course, surprise with inventive action. Take “Shaun the Sheep Movie,” released exactly a decade ago: Aardman created a touching story about the desire to escape monotonous life without a single line of dialogue and presented several outstanding chases that would make silent film stars envious.

In the mid-2010s, everything changed. An attempt to create a new series (“Early Man”) was, to put it mildly, unsuccessful, followed by a period of endless sequels for Netflix that clearly paled in comparison to the originals (“Shaun the Sheep Movie: Farmageddon”). The culmination was the release of “Chicken Run: Dawn of the Nugget,” after which it became impossible to ignore the studio’s crisis. Judge for yourself: the daring first part, inspired by war films about escapes from concentration camps, was transformed into a sterile modern cartoon about overprotective parents who literally learn to let their chicks out of the family nest.

Still from the animated film “Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl”

The Return of Wallace & Gromit: A Hopeful Sign?

This digression into the history of Aardman’s recent projects is no accident. Just imagine the anxiety with which fans awaited the return of “Wallace & Gromit.” By the way, it is one of the most decorated animated series in history, with three Academy Awards! Not to mention the cultural significance of the characters, who not only popularized the image of cozy provincial Britain but also transformed the country’s image abroad. This giant of world cinema could easily have turned into another unremarkable piece of content for Netflix. After all, even on paper, “Vengeance Most Fowl” was uninspiring and indistinguishable from previous Aardman sequels: instead of a new plot, a safe return of a 30-year-old villain, and one of the main themes was the ubiquitous and topical artificial intelligence. Fortunately, the worst fears were not confirmed: the new installment, while not outstanding, is a worthy continuation of the great series.

Still from the animated film “Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl”

Strengths and Weaknesses of “Vengeance Most Fowl”

Perhaps the main drawback of the film, especially when viewed in the context of completing a marathon of the entire franchise, is the noticeably reduced density of visual gags, jokes, Wallace’s quirky inventions, and, to make matters worse, an increased number of lines—arguments, monologues, and not always appropriate blockbuster one-liners. Aardman’s hallmark has always been that the studio took the mantra “show, don’t tell” to an absurd level and elevated it to an absolute: half-hour short films fired off references and parodies of classics like a machine gun, poked fun at great writers (Dogstoyevsky!), surprised with new pointless Wallace machines, and delivered masterful visual jokes. The richness of events is understandable and explainable: each frame is a titanic manual labor, so the creators simply could not waste time. Even the first feature film (“The Curse of the Were-Rabbit”) showed that maintaining the same rich density for 80 minutes is impossible. “Vengeance Most Fowl,” however, more often than usual gives the audience time to exhale and even yawn. This has never happened in the franchise before.

Still from the animated film “Wallace & Gromit: Vengeance Most Fowl”

Aardman’s Take on AI: A Heartwarming Message

Of course, “Vengeance Most Fowl” is full of great scenes and funny jokes: take another dog-literary gag (Virginia Woof), a dozen parodies (from “The Lord of the Rings” and “The Shawshank Redemption” to “James Bond” and “Aliens”), and a large-scale chase in the finale—it couldn’t do without a city canal, an aqueduct, and… vintage boots. If there’s one thing Aardman always goes all out on, it’s on-screen chases, showing boundless imagination. However, what makes the new installment truly special is the plot, or rather, the tone and intonation of the creators. A studio that spends weeks toiling over plasticine figures for a few seconds of footage has every reason to mercilessly criticize artificial intelligence and the lifeless generations of neural networks that have flooded the Internet. And yet, Aardman did something else.

Instead of old-fashioned grumbling, there is a simple but effective allegory with Gromit’s cozy garden, which the garden gnome turns into a lifeless place with a set of geometrically precisely trimmed plants and neatly lined paths. Instead of a didactic ending about the danger of a rebellious AI, there is a hint of peaceful coexistence and a touching realization that no machine can replace the contact between loved ones. The ungrateful and often unappreciative Wallace strokes Gromit for the first time—before that, the hapless inventor and lazybones used a machine. This ode to human closeness may seem like too simple a happy ending, but the important message is amplified a hundredfold because the creators convey it with imperfect heroes who literally bear the fingerprints of their makers.