The Unexpected Trend of Self-Remakes in Cinema: Decoding “Silent Kill” and Beyond

“Silent Kill”: A Dark Horse Success

“Silent Kill” has surged past 600 million at the box office, with projections exceeding 1 billion across various platforms. It’s undeniably the dark horse of this summer’s film lineup.

The film adopts a suspenseful thriller approach to address social issues like school bullying. Its core message, “Silence is a killer,” is subtly revealed in the title. It firmly urges viewers not to be perpetrators or silent accomplices in bullying, but to actively resist it in the right ways.

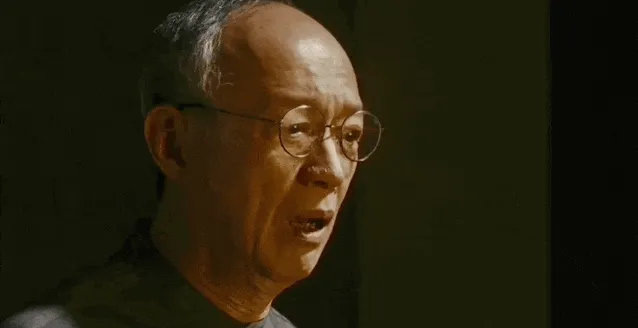

Director Qu Wenli, in an interview, expressed his desire for his films to address social issues and give a voice to the voiceless. The current online discussions surrounding “Silent Kill” suggest that he has taken a successful first step.

The Origin of “Silent Kill”: A Director’s Self-Remake

Following Qu Wenli’s previous work, “Sheep Without a Shepherd”, many speculated about the film’s source material. However, “Silent Kill” is both an original creation and a remake by Qu Wenli himself.

The script was initially completed in 2015, but this version is a remake of Qu Wenli’s 2022 work of the same name, “Silent Kill.” The 2022 version premiered at the Busan International Film Festival and was later screened at domestic film festivals like the Shanghai International Film Festival.

The Trend of Self-Remakes in Film History

Self-remakes are not uncommon in film history, both domestically and internationally. John Woo’s self-remake of “The Killer” is also on the horizon. But what drives this trend of self-recreation?

The Genesis of “Silent Kill” (2022)

The 2022 version of “Silent Kill” predates “Sheep Without a Shepherd” and was initially envisioned as Qu Wenli’s debut film. However, its post-production was delayed due to the creation of “Sheep Without a Shepherd.”

The inspiration for “Silent Kill” came from a social news story Qu Wenli encountered while studying in Taiwan, China. He was deeply moved by the fact that neighbors heard a girl’s cries for help but dismissed it as a family matter. Some even witnessed the suspect dragging the girl into her room but failed to report it.

Qu Wenli realized that “collective silence can be deadly.” He hoped to use this story to encourage people to speak up in similar situations. He remained committed to bringing this project to audiences, expressing his desire for the film to be released as soon as possible during its film festival run.

The Road to the Remake

However, due to uncontrollable factors involving the male lead, which contradicted the film’s original intent, the release plans for the 2022 version of “Silent Kill” were shelved.

In late 2023, Qu Wenli decided to remake the film, hoping to share the story with a wider audience. He stated that he aimed to “innovate further in terms of script, cinematography, art direction, and performance.”

While both versions of “Silent Kill” maintain the same overall storyline and retain many details like animal metaphors, the new version tones down the character of Fang Juezhong. In the original story, this character had strong religious undertones, resembling the “revered one” figure in “The Pig, the Snake, and the Pigeon.”

Overall, the new version is more aligned with universal values for a global audience. Moreover, between the two versions, Qu Wenli gained experience directing “Sheep Without a Shepherd” and the TV series “The Psychologist,” which significantly improved his directorial skills.

Other Examples of Self-Remakes

“Silent Kill” is not an isolated case in recent film history.

In early 2021, Bao Beier’s film “Big Red Envelope” became a dark horse, grossing 235 million. “Big Red Envelope” is a remake by director Li Kelong of his own film “Red Envelope” from four years prior. The plot remained the same, but the cast was upgraded from unknown actors to a “star-studded lineup” including Bao Beier and Jia Bing.

The original “Red Envelope” had a limited theatrical release and received positive feedback. For a director transitioning to commercial films, adapting their strongest script may be the most convenient approach. The success of “Big Red Envelope” seems to support this idea.

Reasons Behind Self-Remakes

Besides market considerations, there are other reasons why directors remake their own films.

Some directors create different versions of the same script for different countries, adapting it to the local culture.

Shunji Iwai created “Last Letter” in both China and Japan, using the same core story.

Letter exchanges, a recurring motif in Shunji Iwai’s work, are central to both films. Chen Kexin served as a producer for “Last Letter,” ensuring its localization. However, due to Iwai’s core creative style, many felt that even with solid localization efforts, the emotional depth and logic of “Last Letter” were not as well-suited as in the Japanese version.

The two versions also differ in their visual language. “Last Letter” frequently uses rotating shots, while “Last Letter” often incorporates aerial shots, increasing the sense of distance between characters.

Some directors remake their work almost as a “copy.”

Austrian director Michael Haneke remade his 1997 film “Funny Games” ten years later. Aside from replacing the German-speaking Austrian actors with English-speaking European and American actors, the remake was nearly identical.

Haneke stated, “If you are a follower of the ‘teapot in Ozu’s films,’ you will know my interest in shots. The 2007 ‘Funny Games’ is not only a shot-by-shot remake but also strives to be as consistent as possible with the original’s setting and proportions.”

In Hollywood, production companies often remake successful European films. Some directors insist on directing the remake themselves to ensure the original intent is preserved or to break into Hollywood.

Chilean director Sebastián Lelio’s “Gloria” and “Gloria Bell” were released only five years apart. The director maintained the characteristics of the original, refusing to bow to Hollywood’s commercial pressures, only replacing the film’s soundtrack and actors to avoid cultural differences.

A similar case exists in the Chinese market. Malaysian director Guo Xiuzhuan transplanted his film “Guang” to China, creating an almost identical remake titled “Unbreakable Brothers.”

With the development of cinema, technological advancements have driven creativity. Changes in societal understanding have also led directors to significantly alter their approach to filmmaking, prompting them to revisit and recreate their projects.

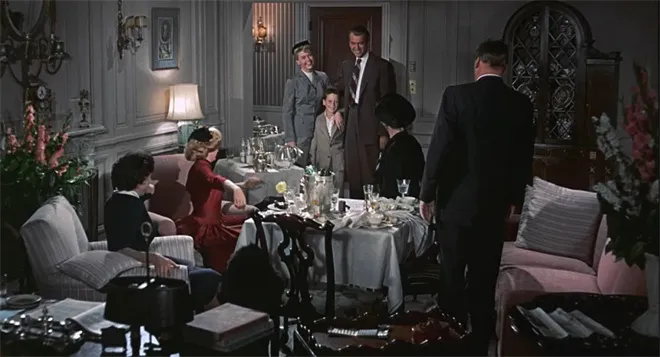

Alfred Hitchcock’s “The Man Who Knew Too Much” is a prime example.

The two films were released over 20 years apart. Film technology had evolved from black and white to color. The final version not only had changes in picture quality but also adjustments in content and style. Even Hitchcock himself commented, “The 1934 ‘The Man Who Knew Too Much’ was the work of a talented amateur, while the new version was created by professionals.”

Another typical example is Yasujiro Ozu’s 1959 remake of his 1934 film “A Story of Floating Weeds,” titled “Floating Weeds.”

The film transitioned from silent black and white to color with sound. These technological advancements prompted the director to change his cinematic language. To this day, “Floating Weeds” is considered by many film enthusiasts to be a peak creation in Yasujiro Ozu’s career.

In fact, Yasujiro Ozu’s filmography includes more than just this one “self-remake.”

Many people know Wu Yonggang’s classic silent film “The Goddess,” but perhaps fewer know that he remade it four years later as the sound film “Rouge Tears.” Unfortunately, the director continued to use silent film logic when transitioning to sound, and “Rouge Tears” was overshadowed by the brilliance of “The Goddess” in film history.

With these examples in mind, one can’t help but wonder what new possibilities John Woo’s remake of the classic film “The Killer” will bring. Chow Yun-fat’s performance in “The Killer” is legendary. Will the director’s remake bring a new kind of violent aesthetics?

From Film to Series: Expanding the Narrative

Many directors also remake their films into TV series or adapt their short films into feature-length films.

French director Olivier Assayas remade his 1995 film “Irma Vep” into an HBO miniseries. This transition from film to series is almost a director’s reconstruction of the same theme to fit the aesthetics of a new era.

Some stories inherently have more room for narrative expansion. For example, director Chen Huiyi expanded the film “Heroes Among Heroes” into the TV series “The Water Margin.” The actor Xu Jinjiang’s portrayal of the flower monk served as a fulcrum, continuing the creation across two different mediums.

With the development of cinema, more and more directors are choosing to create feature-length films from their successful short films.

The success of the short film leads to greater financial support, and the expansion of the story facilitates the incubation of a mature project. The animated film “Falling From Earth” and the film “Dao Cang” both have short films of the same name.

The director’s self-remake inevitably gives the film more space. Film itself is an “art of regret,” and this model allows regrets to be constantly repaired. Is it transcendence or stagnation? It is a different kind of challenge for directors.