The main competition section featured films by Jafar Panahi, Ordinary Accidents, and Mario Martone, Outside.

Jafar Panahi’s Return with Ordinary Accidents

Seven years after winning the Best Screenplay award at Cannes for 3 Faces, Iranian director Jafar Panahi returned to the main competition with Ordinary Accidents. This new film continues Panahi’s signature style, using a fantastical story to explore the meaning of freedom in Iran.

Since picking up a camera, Panahi has faced numerous hardships—arrests, imprisonment, house arrest, travel bans, and even a prohibition on filmmaking. Yet, these challenges have never diminished his unwavering spirit. He has persisted in filming, even resorting to underground, secret creation, overcoming obstacles with limited resources, all to continue shooting and defend freedom. Panahi’s films are minimalist in style but highly political. He often employs a semi-documentary approach, blurring the lines between fiction and reality, constantly exploring the fragility of individual freedom and the complexities of social connections. This exploration is particularly valuable in a society governed by censorship and unspoken rules.

The plot can be summarized as “small accidents leading to big events.” Panahi, a director who believes that filming is resistance, uses his lens to depict the Iranian people struggling for freedom. In Ordinary Accidents, the people secretly confront government officials. While Panahi returns to fictional narrative, he never abandons the consistent themes of his work. More importantly, we once again witness his keen insight and profound analysis of his homeland, Iran.

Mario Martone’s Outside: A Tale of Imprisonment and Expression

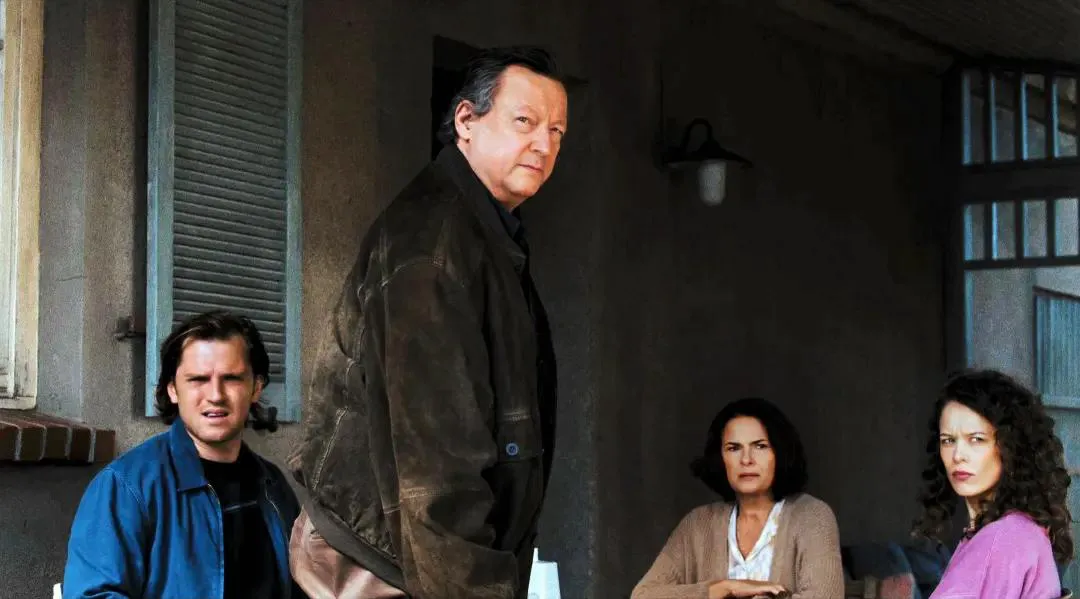

Following Nostalgia in 2022, Neapolitan director Mario Martone once again entered the Cannes main competition with Outside. The film is inspired by Goliarda Sapienza’s autobiographical novel University of Rebibbia, set in the 1980s, which recounts her months in prison for jewelry theft.

Martone chose Valeria Golino to play the lead role. Golino, also a director with a strong connection to Cannes, has had her directorial works selected for the festival multiple times. Her film Euphoria, was a standout. Golino described the protagonist, Goliarda, as someone who “doesn’t listen to anyone, has a unique style that not everyone can accept. Her writing is beautiful and layered, with incredible expressiveness.”

Overlooked Gem: Christian Petzold’s The Third Movement

Beyond the two main competition films, we’d like to highlight Christian Petzold’s The Third Movement, featured in the Directors’ Fortnight section. Based on the director’s reputation and the film’s quality, it seemed a natural fit for the main competition. The fact that it didn’t make the cut is baffling. With several arguably less deserving works in the main competition, Cannes’ decision has sparked considerable discontent.

Unfortunately, Cannes seems to have such cases every year. Last year it was The Forgiven, the year before Close Your Eyes, all generating similar controversy. This year, it’s the turn of Petzold, a leading figure of the “Berlin School.” We’ve translated the Presskit for The Third Movement, where Petzold discusses the film’s creation in detail (see below).

The Third Movement continues the creative partnership of Petzold’s recent films, with Paula Beer in the lead role. As Laura (Paula Beer) drives her red convertible through the countryside, she exchanges a glance with Betty (Barbara Auer), dressed in black and painting a white fence. As Petzold puts it, “She was chosen, like in a fairy tale.” Their lives begin to change after this exchange.

The film premiered to widespread critical acclaim, with high scores from the discerning editors of Cahiers du Cinéma and multiple perfect scores in the ICS Cannes Critics’ Grid. Without a doubt, it is one of the best films at this year’s Cannes. Its exclusion from the main competition is a misstep on the festival’s part.

Early Buzz: Ordinary Accidents a Potential Winner

Based on early reviews, Jafar Panahi’s Ordinary Accidents is a strong contender for an award at this year’s Cannes. While its performance on the ICS Cannes Critics’ Grid is moderate, it scored 3.1 on the Screen Cannes Critics’ Grid, tying for first place with The Prosecutor. In the French media grid, it also received an impressive four Golden Palm leaves, currently slightly below The Apprentice. In contrast, Outside has received less favorable scores, currently at the bottom of the Screen Cannes Critics’ Grid with an average score of 1.

The Third Movement Details

Original Title: Miroirs No. 3

Director: Christian Petzold

Writer: Christian Petzold

Cast: Paula Beer, Barbara Auer, Matthias Brandt, Enno Trebs, Victoire Laly

Genre: Drama

Country: Germany

Language: German

Release Date: May 17, 2025 (Cannes Film Festival) / October 2, 2025 (Germany)

Runtime: 86 minutes

Classical painting with flowing desire, a true successor to Fassbinder, now an art form.

Many films at this year’s Cannes explore the theme: I don’t belong here, I’m not in your story. Petzold tells the story of how fate brings two women into each other’s lives, fitting together like wedges, leaving gently after completion. The Third Movement transforms from myth to Grimm’s fairy tale, with Betty, like a witch, finding her lost daughter under the protection of Mother Earth and the forest. A concise piece, quiet and beautiful.

Petzold tells this story in an extremely smooth way, which is comfortable for him.

A mediocre work in Petzold’s current creative phase, his mediocrity is failure. This time, he is just rehashing his previous works, even the way he delays the suspense of the play is exactly the same. Undine and Red Sky were next-level works for me, but now he has returned to his former creative path. After watching it, I finally understood why Fomo grabbed Schlinski’s Sound of Falling from Berlin and rejected this one.

Interview with Christian Petzold on The Third Movement

How did the idea for this film come about?

While filming Red Sky, we shot a scene outdoors around a table where Paula recited Heine’s poems, which gave me the idea for this film. The atmosphere that day was both relaxed and a bit tense, because a lot was happening around Paula as she recited the poems. To ease the actors’ emotions, I told a story about Heine and Kleist, because they both mentioned it in their conversations. I told about a letter Kleist wrote to a friend, in which he described a sleepless night he spent in Würzburg. Kleist was full of anxiety, running through the streets, trying to escape from a door in the city. When he stood under that door, he looked up and saw the construction of the portico. He discovered that the portico was supported by a pile of stones, which supported each other, preventing them from falling.

Kleist exclaimed that it was precisely at the moment when the stones were about to collapse that the vault was formed, and it was these vaults that supported human survival. Kleist said that it was at that moment that he felt a great sense of comfort. I told this story to the actors, and we thought it was a beautiful metaphor for the film. Film, or fiction, tells just such a story: something is about to collapse, and in this collapse, new vaults, structures, and groups are created. The inspiration came from this metaphor: a young woman meets a broken family, and this family will be rebuilt through her appearance. This was the initial idea.

{On the Bridge}

At the beginning of the film, we see Paula Beer (as Laura) leaning on the railing of a bridge, looking down, but this scene is not explained.

At the beginning of the story, we know nothing and can only interpret it from subtle clues. The background is the noisy city sound, cars speeding by, mixed with intermittent music. In the picture, a young woman is standing on a bridge near the highway. When she leans over and stares at the flowing water under the bridge, the picture reveals a bit of romance, reminding Paula of Undine. The woman doesn’t speak or have an obvious rhythm, she is just immersed in her own world. I like the film to present this kind of self-existence at the beginning, not rushing to explain anything to the audience, but letting the audience take the initiative to approach, start observing, understanding, interpreting, and feeling. Then, the woman walks to the water’s edge and hears the sound for the first time - the rustling of wind blowing through the leaves and the sound of paddling water. She looks up and sees a man paddling a paddleboard, a picture reminiscent of Böcklin’s painting Isle of the Dead, depicting the ferryman guiding the dead across the other shore. This is the first image she perceives: death.

{The Encounter}

Laura’s state of alienation from the world runs through the opening of the story - whether in her apartment, in the car, or in the port.

Laura is always detached from everything around her. She sits in the car, while others listen to music, talk, and plan for the future, but she cannot participate. One day, as the car passes a house, a stranger dressed in black and painting a fence makes eye contact with her. The woman’s gaze does not linger on anyone else, only on Laura, and a wonderful connection is quietly established between the two. In a sense, Laura has been “chosen,” like in a fairy tale. The woman holding the paintbrush seems to have welcomed a princess to her “witch’s cottage.”

They meet again before Laura’s accident.

The young people’s weekend should have been pleasant, but Laura can no longer interact with this world. When the producer says to Laura’s boyfriend: “Send this dramatic girl to the station, and then we can leave,” it’s as if Laura doesn’t exist. For me, it’s important to make the audience understand how easily a person can be “erased from the map.” The audience can feel that Betty really stopped the car this time. The first time was just passing by, but this time it was a confrontation. Their eyes meet, and at that moment, it’s as if they have reached a silent agreement.

{Red Convertible}

Laura and Betty’s encounter begins with an accident, but the film does not directly present this accident, and the audience can only hear it happen.

The road is empty, only the chirping of birds, as if nature is also disturbed by this sudden change. Then, the red convertible is stranded alone on the side of the road. This red convertible is like a symbol from a fairy tale, it runs through film history, like the shoe that Laura lost after the accident. The red convertible comes from the world of fairy tales, but the prince here is dead.

The impact of the car accident on Laura is only shown in an implied way. She once said: “I should feel sad, but I can’t feel sad.” This is a recurring theme in your films - dissociation.

Yes, Laura can only survive through complete dissociation. This dissociation makes her extremely indifferent to the past. In this film, she is actually reborn after the accident. Betty takes her home, covers her with a blanket, tells her stories, teaches her how to paint fences, introduces her to the knowledge of plants, awakens her senses, and gives her her first bicycle… These are all the most basic elements of life. In fact, Laura has experienced a completely new growth process in just a few days, which has nothing to do with her past life. It’s as if she has been given an absolute new beginning.

{The Garage}

The father and son appear relatively late in the film. Initially, Betty mentions them, then we see them in the garage, and then they accept the dinner invitation, unaware of what is about to happen.

The two are drinking beer and eating Serbian bean soup in front of the garage. At this time, customers arrive one after another, and it is clear that something illegal is happening here. In the background, you can see some old items left over from East Germany, such as an old tractor, plus the wreckage of those abandoned cars, the whole scene reveals a bit of American style. Obviously, their repair business is not very good, perhaps because of the consumerism of capitalist society, people are used to discarding broken items instead of repairing them.

These two can repair almost anything, and the essence of repair is to understand the object and find out where it is broken. They also yearn to see the broken parts of this family, but they are powerless. Their lives are in a temporary state, like in a camper van camp, living in two simple rooms next to the garage. When they return from dinner, the son walks into his storage room, with a clothesline in front of the door, and the father smokes in the twilight. This temporary feeling is conveyed with just a curtain and a clothesline. And what we can’t see is the charm of the film, which inspires our imagination. Just as we have never seen the room of the deceased girl, but we can perceive and guess, which makes the story richer and deeper.

{Eye Contact}

In the film, we see the two men arrive at the door from Laura’s perspective.

This narrative technique is used throughout the film: first, the characters are shown from an objective perspective, such as the father and son in front of the garage, and then they are switched to the subjective perspective of other characters to look at them. At this moment, we observe them from Laura’s perspective - how they get out of the car, how they check the repainted fence. This change of perspective presents them in a completely different image. At the beginning of filming, I and the director of photography Hans Fromm established this basic principle: alternate between objective and subjective perspectives, because a family is composed of both objective facts and subjective emotions, and this contrast must be reflected through rhythm.

In the scene where the four gather for the first time, the narrative unfolds from Laura’s perspective. But then, we don’t see Laura preparing the food, and there are no shots in the kitchen showing the waiting family. Because at this time, the tense atmosphere, anticipation, extra tableware, the son holding the plate, the meal, and the eye contact all happen in the triangular relationship between the family members, not within Laura’s perspective. Here, Laura becomes the “object” in the family relationship.

{The Road}

The road connecting the garage and the house, composed of two lanes separated by grass, symbolizes both the distance between the two worlds and the relationship between them.

When we first saw this road and the house in front of it, I was very excited. The road has only two lanes, and the vanishing point of the lane lines creates an excellent sense of depth in the picture. Later, this road also played an important role in the bicycle scene, because everyone was riding in their own lane. It is also crucial to the beginning of the story - the young people leave the city and drive into a road that is almost just a country path. This immediately means that they have entered an unfamiliar area where the navigation system may fail and fairy tales are possible. Deviating from the main road, the story unfolds.

Our filming locations were very close to each other, and almost all scenes were completed locally. I think it is important not to mechanically piece together various unrelated locations, but to present the local world as it is and discover its unique charm from it, rather than beautifying the world from the outside with money. Because the filming locations were so close and we filmed in chronological order, we were able to make full use of local resources and natural changes - the summer sun, the breeze, the autumn weather changes, and the magnificent sky before the rainstorm.

{Lies and Laughter}

Especially the son Max, he finds it difficult to accept Laura’s presence.

There is a scene where Max comes home, and we see him trying to figure out what is really happening. Who is this young woman? She is working in the vegetable garden, handing him coffee, as if this home belongs to her. This makes Max furious. At the same time, the sound of the piano tuning comes from the background, and we learn that she is learning the piano. She also says: “I think your parents also want to be alone for a while…” At this moment, we feel that Laura has integrated into this false life. Max also senses this, and he tries to resist, but at the same time, he also realizes that he actually likes Laura. This is also what I like about the film. The son senses the lie, knows that this lie will eventually lead to disaster. But he cannot destroy this lie, because he does not want to destroy his parents’ hard-won brief happiness.

One of the most beautiful scenes in the film is the moment when Max and Laura laugh at the same time.

They are sitting at the table in front of the garage, listening to Frankie Valli’s song… The actors didn’t know how to act at the time. They are in the situation of the characters, knowing what they are experiencing, but the characters themselves are not enough to support them being filmed in this scene for five minutes. It is actually impossible to “act” it out, and the two realize this at the same time, look at each other and laugh. At this moment, they are no longer just Laura and Max, but Paula and Enno. And this laughter is exactly what the scene needs, because at this moment, they are just themselves. He is no longer the failed son, and she is no longer the substitute girl. This moment is very important to me, and I wanted to capture the way they laughed spontaneously.

{Lost Child}

Losing a child is a recurring theme in your films such as Ghosts and Wolfsburg.

There are two different types of stories that can be told about missing children or parents who have lost children, like Hansel and Gretel and The Virgin Mary’s Child in Grimm’s Fairy Tales. These two themes have always interested me. When we are young, we are afraid of getting lost; when we become parents, the biggest fear is losing our children. There are many terrible things that can happen in life, but these can also bring people closer together. However, losing a child is almost a pain that parents cannot fully heal. Whether the child is kidnapped or has an accident, parents need to construct a narrative of guilt to rebuild order in this lost world, and this narrative often ends up blaming others or themselves, or even leading to the breakdown of the couple’s relationship. But in our film, there is almost no direct narrative about the missing Ilena, and there is no in-depth investigation of her, only vague hints.

For us, everything becomes clear from the moment Betty accidentally calls Laura “Ilena.”

Laura knows that something is wrong with this family. She knows that there must have been someone who lived in this bedroom, played on this piano, and rode on that bicycle. But now all of this belongs to her. The shoes fit, she likes the T-shirt, and even Betty’s care makes her feel happy, which is a comfort to her, even though all of this is false. But the focus of the film is not to dig out the secrets behind the plot, the film focuses on how these people cope with their respective traumas and losses, and what they expect from life.

In essence, Laura walks to the window at night and sees Betty standing on the road in front of the house, and the two reach an understanding. Betty is always in that place, she paints the fence there, and when she can’t sleep, she comes here, always waiting for her daughter to return. This scene is like a horror movie. Laura looks down from above, and Betty turns around and looks up at her. At this moment, a certain understanding flows between the two: “I know I am playing a role for you here, playing your daughter. We don’t say it, cherish this time, cherish every second.” At that moment, Betty is no longer looking at her deceased daughter, but at her “princess.” This kind of moment and gaze appears repeatedly in the film.

{Ominous Premonitions}

When Laura plays Chopin’s music for the family, it is as if she has opened a door for Ilena, and it seems that the real side temporarily overcomes the false. That was the first time Laura had played in a long time.

This scene is of great significance to Laura. When Betty says: “Can you play for me?” the atmosphere is chilling. Laura is silent for a few seconds, then gets up and responds lightly: “Yes.” She does not succumb to this uncomfortable request, but responds with a transcendent attitude, conveying the belief that “Now, I am going to play, not for you, but for myself.” At this moment, she has accomplished something important. In a sense, this echoes the ending scene - “I am here, I am saved.” The family members look at her playing the piano, only seeing her back, maybe they are seeing another person - the missing daughter/sister. When filming, we let this scene last longer, capturing the family’s emotions and tears, but when editing, we chose to end it early to give the scene a lingering charm and shock similar to an earthquake wave.

This almost becomes a farewell to Ilena.

Something changed at that moment, but no one can say exactly what. The parents go to the river to pick plums together, and the son leaves in a hurry. They have just witnessed the deceased daughter/sister. I think a separation has just been staged, but Laura has not yet noticed it. Laura goes to pour herself a cup of coffee and sits on the terrace, feeling very good. She feels released, and being able to play the piano again is also a relief. Just then, the dishwasher explodes.

{A Lone Boat at Sea}

Although the film does not directly present it, we can still feel that the family of three is working hard to maintain some form of reunion after the disaster, and is still continuing to fight.

When writing the script, I often imagine that the film is a dream of a character. When creating Phoenix, I imagined Nellie in Auschwitz dreaming of a life that was not forever torn apart by the Holocaust, dreaming of regaining lost time. And here, I conceived of a young piano student playing Ravel’s The Third Movement, and in the performance, embarking on a fantasy journey to a family that can make her happy, the subtitle of this piece is A Lone Boat at Sea. Listening to this music, we can feel the storm approaching, and the boat may capsize at any time. And this family has sunk because of the death of their daughter. Now, the wreckage is floating at sea, and these three survivors are trying to build a lifeboat with these pieces. This is the story of the film. The three castaways get closer to each other, try to piece together the pieces, build a raft, and try to land on land. This is the metaphor of the film.

There is also a fourth victim, from afar, pushed by the waves, who also joins the construction of this lifeboat.

That’s right, only by gathering all the pieces can they build this lifeboat, use it to survive, and finally reach land. Perhaps, in the final analysis, all films are about how people try to piece together a lifeboat from the ruins. This is what the film is about: how to survive, not just live.

{The Team}

You have worked with all the main actors many times. How important is this continuity to you?

I really like this sense of teamwork, being able to film with them, and at the same time already conceiving the next work. During the filming of Red Sky, we discussed The Third Movement, and if it weren’t for the working and trusting relationship we had established before, I wouldn’t have been able to tell this story at all. For example, Matthias Brandt’s Richard in the new film is similar to Helmut in Red Sky, and the roles of Paula and Nadia and Enno Trebs in the last two films are also related to each other. The actors are not only interpreting everything in this world, but also based on the understanding and continuation of the previous roles.

In Home for the Weekend, Barbara Auer played a mother who had to strictly arrange her life in order to live a secret life, and had to replace her daughter’s life, world, and school, which eventually led to disaster. Barbara also brings some of the qualities of this character to our new film. I like working with the same group of actors many times, not only because they are all excellent, but also because they have accumulated rich experience through their performances in previous films, and can give new roles a deeper level of expression.

{Ideal Life}

Ideal life is almost a recurring theme in your films. At the end of Yella, it seems that the audience is more unwilling to give up that ideal world, but here, it is more the characters themselves - a bit like the mother in Ghosts.

At first, we even planned another ending, staying in that ideal life: the family is sitting on the terrace, seeing Laura coming back, pushing open the garden fence. But this treatment is false, it fits my desire for harmony, but it is not suitable for the film. When we were filming The Third Movement, the war in Ukraine had entered its third year, the clouds of Trump’s victory loomed over the sky, and there was a tendency towards fascism all over the world. I longed to stay with this family in this beautiful house in the Uckermark Highlands, with these wonderful people, until the world returned to normal.

This desire for harmony gave birth to the fairy-tale ending of “Laura finally coming back and everyone sharing plum cake on the terrace.” But obviously, it is not appropriate to do so, and the story cannot end like this. What we ultimately need is not a fairy tale, but an awakening. Let these three people continue to live not only as a family, but also as independent individuals, and let Laura truly start her own life. This lifeboat will send these survivors to different places on the shore, and then they will no longer need to fantasize about life. These four people have lost their sense of the real world, and they are no longer interested in touching, feeling, tasting, and watching. And as a group, they have successfully awakened each other’s senses and relearned how to be human.

So they were able to go their separate ways.

In the concert hall, Betty, Richard, and Max witnessed that the person they were protecting was able to stand on her own.