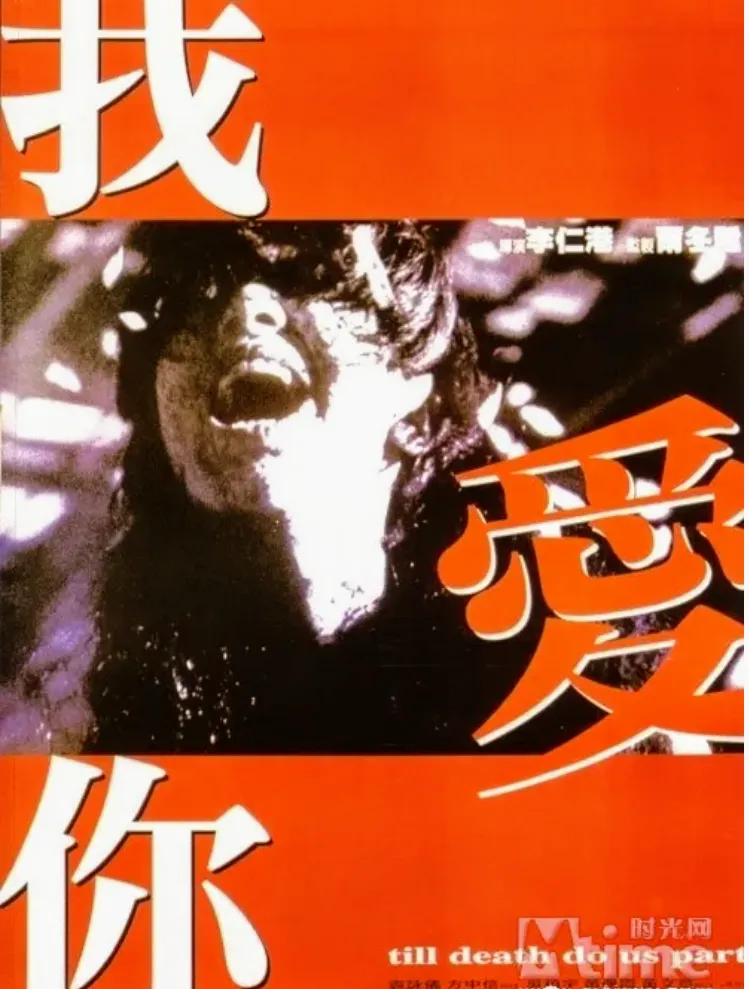

This is a 1998 Hong Kong film titled *Till Death Do Us Part* in English, and *我爱你* ("I Love You") in Chinese.

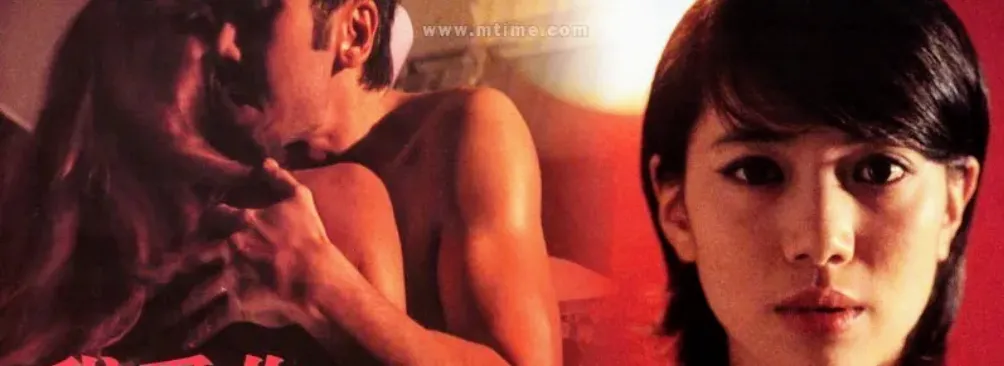

Anita Yuen was crowned Miss Hong Kong at the age of 19. By the time of this film, she was already 27—still delicate and fresh-faced. When people are young, even the plainest faces carry a kind of gentle charm. What’s rare about her, though, is the complexity in her wide, deer-like eyes.

We all love children for their innocence and naivety. But when such rare qualities appear in an adult, they are often quickly lost or cast aside.

Anita Yuen plays a woman full of childlike qualities. Her husband, Alex (played by Alex Fong), was her classmate in school. Now that Alex has entered the workforce, he serves as an officer in the ICAC (Independent Commission Against Corruption). At the time, the ICAC faced immense challenges—sometimes investigating powerful figures meant stepping on the toes of the triads.

Alex couldn’t possibly share this kind of pressure with Bao Bao. A woman who lives in a world of comics and innocence wouldn’t understand the tangled darkness of reality. And men rarely like to confide, anyway.

At the beginning of the film, Bao Bao leads a blissful, carefree life as a housewife. Director Daniel Lee tells the story visually with richness and restraint—a few simple shots are enough to reveal where the man’s heart truly lies: with another woman, one brimming with vitality and strength.

At that point, I sighed from the heart. On the surface, Bao Bao seemed to have married a promising, ambitious young man. But she didn’t realize that even a man who hasn’t weathered many storms can have a fragile inner world. What he really needs is an anchor—while she is but a delicate flower.

As the film progresses, Bao Bao's emotional defenses collapse entirely. The whole color palette shifts into deep shades of blue. Even with a lawyer doing everything he can to shield her, she continues to deteriorate, unable to stop the downward spiral.

I found myself deeply drawn to the film’s lonely blue tones. Whether it’s the inky blue of water at night, or the rich twilight blues of a winter sky, it brings a strange kind of joy. It's like a bell jar made of glass, like those that hold lily of the valley, enclosing the world and sealing away all pain and ugliness.

When a man is childlike, a perceptive woman will do all she can to shield him from the harshness of the world. But when a woman of equal standing possesses that rare innocence, both men and women tend to frown and tell her to grow up.

The 1990s were a dazzling, kaleidoscopic era. Once, at a street barbecue stall, Xiao Hua said to me, “Some things, once they’re gone, they’re just gone.” The ‘90s I muddled through so aimlessly have long since faded, leaving behind only these beautiful films that fill me with wistful sighs.

I’ve always had a special love for experimental and avant-garde cinema, and the experimental films of the ‘90s feel like rare treasures.

These films, often light on plot and highly abstract, allow you to project your own drifting emotions onto them. Truth be told, I don’t really understand them—but I love their atmosphere of decay and freedom, and the sense of having all the time in the world to waste.

It’s like when a teenager gives up their studies for some distant, illusory ideal or love—such bravery is deeply moving, and also heartbreaking.

There was a girl who lived in the front row of my building. One evening, after dinner with my family, I saw a boy quickly retreat from her window. At the time, their relationship caused an uproar at school and in both of their families. Their academic performance receded like the tide. Later, I heard the adults say that the two of them would meet in the small park behind our building, embracing as they watched the moon. The adults spoke with detached indifference, as if it didn’t concern them, but to my ears, it sounded like astonishing persistence. Under such pressure and with so many cruel words thrown at them, they could still look at the moon together—what a romantic thing that is.

I imagine that if, years later, they could still hold on to their original feelings, and think back on that moonlit night, it would shine in their memories with a brightness and clarity never seen again. What a beautiful thing that would be.

As early as 1998, Daniel Lee was already interpreting the harsh realities of romantic relationships with such bleakness. If we had understood this story back then, how would we have chosen to live our lives afterward?

I think I would still have wasted my time.

Now, amidst the overwhelming flood of TikTok videos, there are still fragments of artistic beauty scattered throughout—but they’re often ignored, just like those experimental avant-garde films.

Back then, I used to see elderly people on Hong Kong TV watching old Cantonese melodramas, and I’d wonder what could possibly be interesting about such ancient films. Now, I realize just how shallow I was.

At this point in her career, Anita Yuen delivered one of her finest performances. Afterward, her films would never again have the same spirit or vitality.

Douban, that haven for artistic youth, is filled with short reviews beneath this film—testimonies of astonishment and disillusionment.

In truth, many separations aren’t the fault of marriage or even human nature. Ironically, the ones at fault might be those who never changed, those who stayed simple. But then again, can we really say the simple people are wrong? The real mistake lies with those who misinterpret the madness of the times.

But people always need to find a scapegoat.

When Alex asks for a divorce, Bao Bao is still in a daze. She softly moves toward him, still trying to welcome him, not fully realizing what’s happening. She’s in a phase of buffering, of processing. She still dresses up and invites Alex out, trying to win him back. She has a kind of unknowing courage.

Later, when their daughter is burned and lies in the hospital, she wraps her soft arms around Alex and says, “I won’t close my eyes. If I close them, you’ll leave. I wasn’t playing with fire—I just wanted to make alphabet soup for Mom because she’s unhappy. Daddy, will you come watch me be the Little Mermaid?”

In that moment, Alex’s heart softens. But shortly after, while carrying out his duties, he’s kidnapped by the triads. Having escaped death, he doesn’t hesitate—he runs toward the woman he loves in that moment.

Everyone only gets this one life.

At this point, Bao Bao is cast into her own personal hell—her lover declares that he wants to raise her daughter with Alex.

And just like that, when you're weak, everything around you can be taken away.

From this moment on, Bao Bao begins to mentally unravel. Yet even in her breakdown, there’s something heartbreakingly beautiful about her. Though director Daniel Lee treats Bao Bao with cruel realism, she still possesses beauty and youth.

Extreme close-ups linger on Anita Yuen’s young face—still flawless, still radiant.

When Bao Bao loses control during the custody battle for her daughter, she suffers a devastating defeat. In her anguish, she goes to Alex’s new home, and takes his lover hostage with a knife—dragging her up to the rooftop...

He asks Bao Bao, “What do you want?” At that moment, her eyes are still fixed and blank. And then she says the most beautiful and devastating line in the entire film:

“I want things to be the way they used to be. You picking me up from school every day, stacking books to look taller and smiling at me. Kissing me every morning. I want to hear it again—'In sickness and in health, in poverty or in wealth, I will cherish and care for you always.'”

Then, she lets go—and leaps.

Maybe if this film were released today, everyone would feel uncomfortable. Deeply uncomfortable about such a tragic character.

But in the quiet of night, lying next to the person you love—or maybe no longer love—watching the trees sway gently outside the window and the passersby under the streetlights… might you not remember that, long ago, we too once took a brave leap in the name of love?

Bao Bao defended the fairytale she held in her heart with all the courage she had. But people are different. Sadly, not everyone believes in the same dreams.

Films like this are always misunderstood by those with limited perspectives. Reduced to simplistic conclusions, distorted by an era that no longer has patience for nuance. Passed from mouth to mouth—through a hundred, a thousand retellings—Bao Bao becomes “crazy.” Extreme. Difficult. A problem.

And in the end, people just say: “Love fades, doesn’t it? Better focus on making money.”

No one sees the childlike woman who gave her life for what she believed was true love. But that kind of conviction is also a statement—it means someone still believes in love that never dies.

By the time I reach this part of the writing, you probably expect me to give an interpretation—something rational and clear-headed, or perhaps soft and empathetic.

But I won’t.

Because everyone’s understanding is unique. Use your own experiences to interpret this story. Use your own judgment to write its final chapter.

I have no right to dictate what you should think. I just want to remember these beautiful and brutal images.

To remember their youth—and mine.

To remember those drifting, windblown treasures from Hong Kong cinema. *Juliet in Love* and Judy’s emotional scars. Shu Qi searching for her ex in a KTV and at a barbecue stall in *Love Au Zen*. Sister Wah’s quiet perseverance in *I Love Kitchen*. Mavis Fan’s screen debut in *The Accidental Detective*. Karen Mok’s wild curls in *Four Faces of Eve*. Vivia, the sleepwalking dreamer, in *The World After Romance*. And the beer-drinking, can-throwing rooftop scene between Dayo Wong and Irene Wan in *The Sardine Tin Murder Case*.

I watched *The Sardine Tin Murder Case* at my cousin’s house. I was still very young then, but I already loved the film deeply. His mother was the most hospitable woman I had ever met. She would make thick, flavorful Yellow River carp soup and watch as my family played mahjong, laughing and joking.

But life is unpredictable. In the end, we drifted apart.

Don’t expect any wise words from me—because in the late hours of the night, in sleepy afternoons, and in the cold routines of everyday life, people’s thoughts shift in an instant. One well-meaning sentence can barely help; it’s far too weak.

So while you still can love, go and love. Love like you've never been hurt before.

Let our love be full of imperfection and heartbreak—full of restless energy and unease. Let all the foolish turmoil, the regrets, the unreachable longings and the fleeting, arrogant joys grow into the fabric of our love.

If we cannot be bound for life and death, then let go with peace. If you cannot be graceful, then fall apart, beautifully.

If we cannot have a perfect ending—and maybe we were never meant to—then at least be true to yourself.

A love that's too repressed becomes too twisted to bloom into something bright and bold.

Because—whether it’s a sunny day or a rainy one—as long as we’re together, joyfully…

As long as we’re together, joyfully…

As long as I can be with you.